What Characteristic Of The Normal Curve Deals With Skewness

So, I was at this birthday party the other day, right? And there was this massive cake, like, gloriously huge. Everyone got a slice, of course. But then, there was this one kid, bless his little cotton socks, who really loved his cake. I’m talking a slice so enormous it was practically a whole cake in itself. He ended up with way more than his fair share, while some of us got… well, let's just say a more modest portion. It was funny, but also a little… lopsided, you know? Like, the distribution of cake wasn't exactly even. And that, my friends, is where our friendly neighborhood normal curve starts to get a little wobbly.

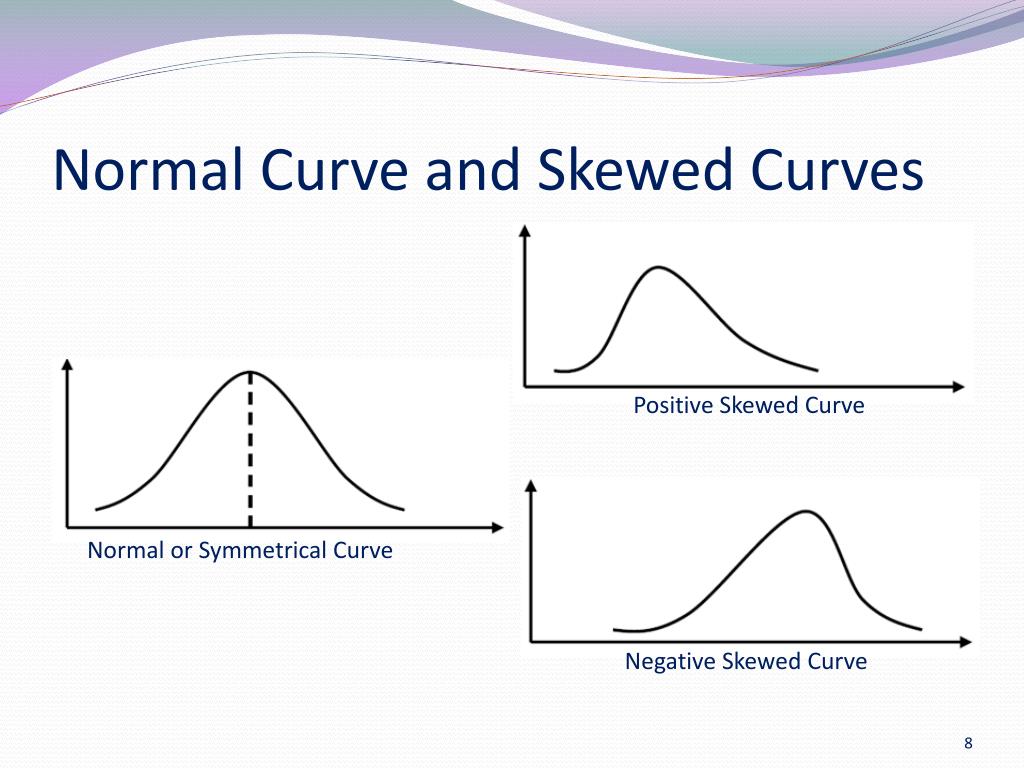

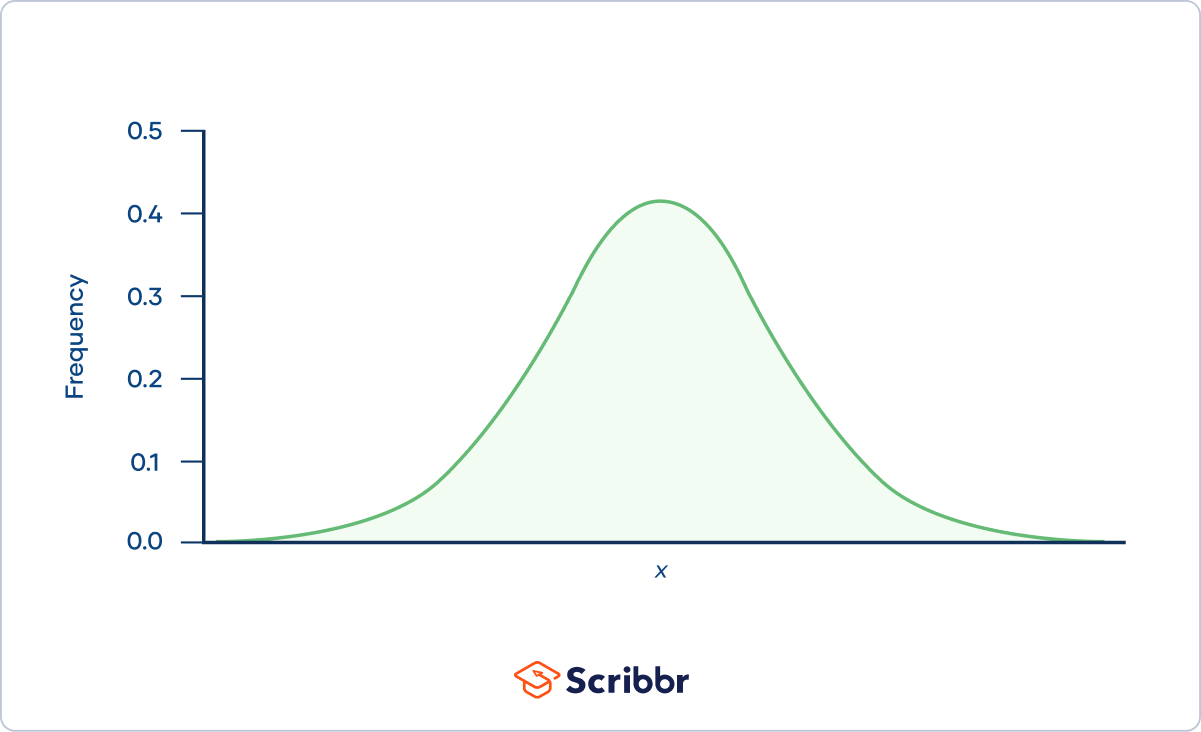

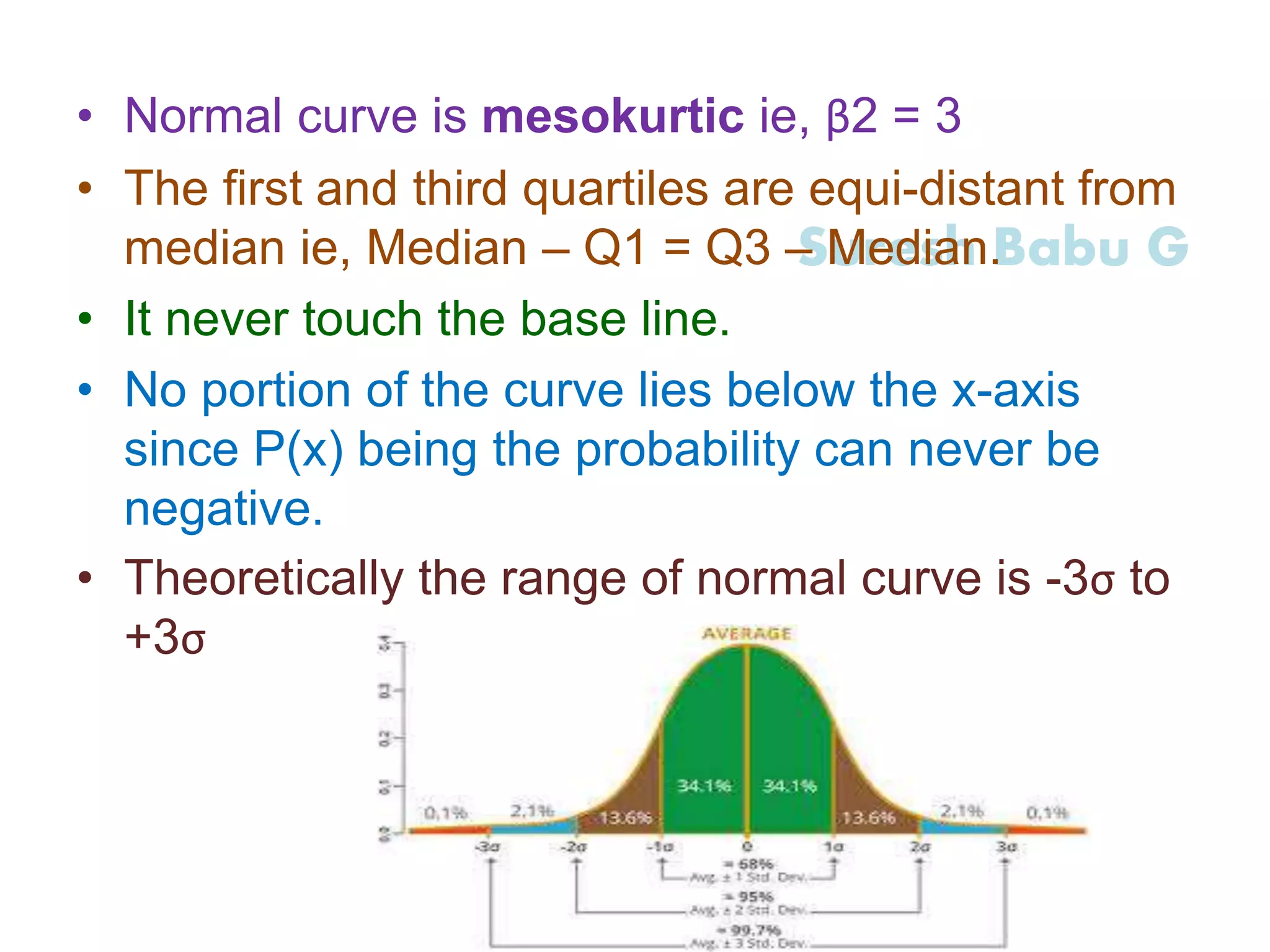

You see, we often hear about the "normal curve," or the "bell curve," and we picture this perfectly symmetrical hump. Like a pristine, untouched snowdrift. Everything looks so neat and tidy, with the peak right in the middle, representing the average. And on either side, it slopes down gracefully, showing that most things cluster around that average, with fewer and fewer outliers as you move away. It's the statistical version of a Goldilocks story: not too much, not too little, just right, right in the middle.

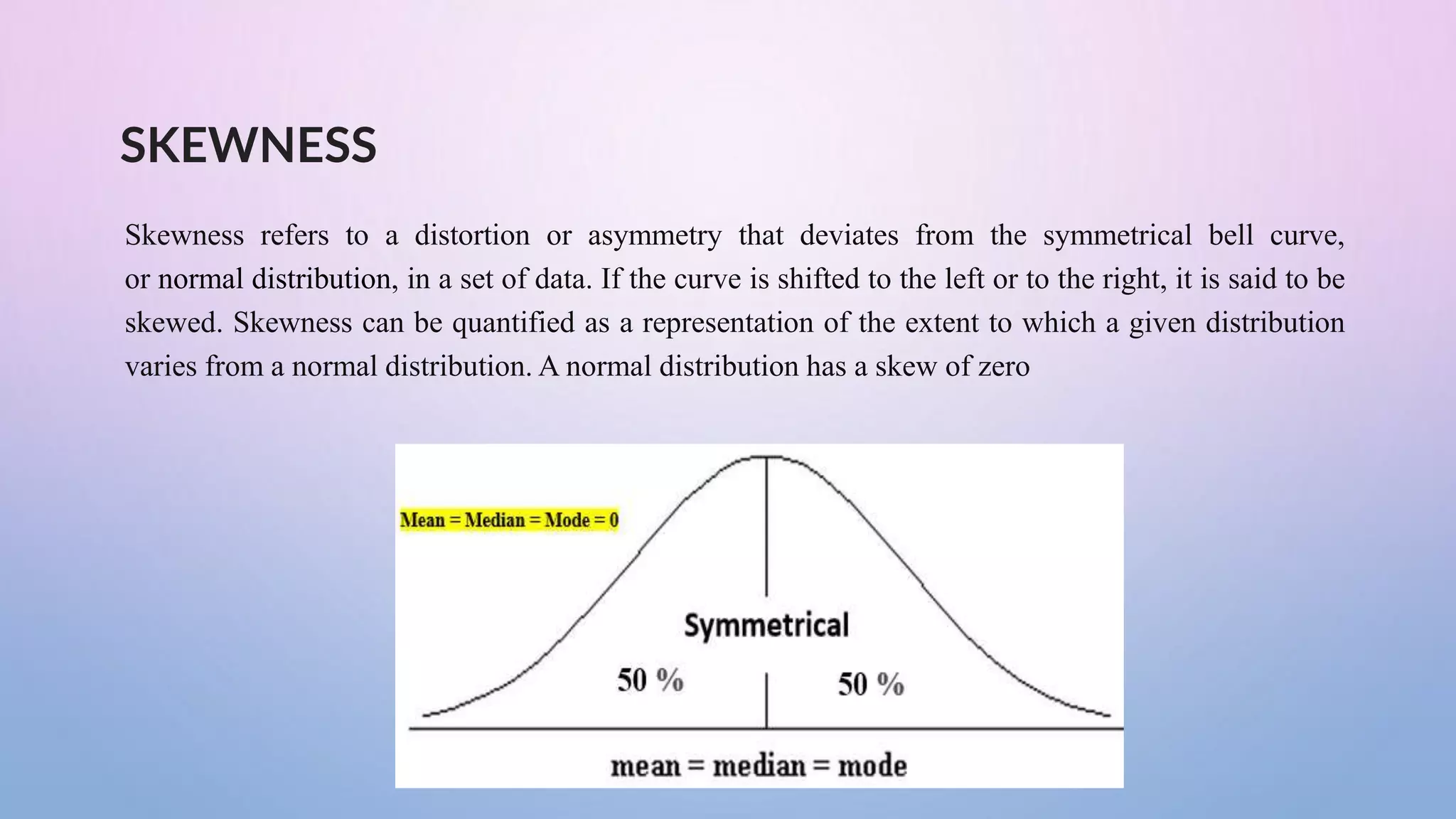

But life, as we know, isn't always perfectly symmetrical. And neither are all data sets. Sometimes, just like that kid with the king-sized slice of cake, our data can get a bit… unevenly distributed. And when that happens, our beautiful, symmetrical bell curve starts to lean. And that leaning, that lack of symmetry, is what we statisticians (and by we, I mean me, sitting here in my comfy socks, pretending to be a statistician) call skewness.

The Not-So-Normal Neighbors

Imagine you're measuring the heights of adult men in a general population. You'd expect most guys to be somewhere in the average range, right? A few super tall guys, a few shorter guys, but generally, it’d look pretty much like that iconic bell shape. That's a classic example of normal distribution. The mean, median, and mode are all hanging out together, chilling in the middle of that hump. It’s the statistical equivalent of a harmonious choir singing in perfect tune.

Now, let's switch gears. What if we're measuring something like, say, the income of people in a country? Suddenly, our choir sounds a bit different. We have a whole lot of people earning a decent, perhaps average, income. But then, we also have a smaller number of people earning a ridiculously high income. These high earners, with their yachts and private islands, are like the opera stars in our choir, singing way louder and way higher than everyone else. And what happens to our nice, neat bell curve when we have these extremely high values pulling at it?

It starts to stretch. It starts to lean. And in this case, with those super-high incomes stretching the tail out to the right, we call it positively skewed, or right-skewed. The bulk of the data is on the left, and the long tail is on the right. It’s like looking at our cake distribution again – if most people got a normal slice, but a few got monstrous portions, the "average" slice would be dragged upwards by those giants. Think of it as the data being pulled by its "heavy" end. Where is the heavy end? Off to the right! Makes sense, right?

And then there's the opposite. What if we're measuring, let's say, the scores on a really easy test that almost everyone aced? Most of the scores will be clustered at the top, close to 100%. But there might be a few unfortunate souls who, for whatever reason, bombed it and got very low scores. These extremely low scores are like the out-of-tune screeching in our choir. They pull the data's tail out to the left.

In this scenario, we have negatively skewed, or left-skewed data. The bulk of the data is on the right (high scores), and the long tail is on the left (low scores). It’s like our cake situation, but instead of a few giant slices, a few people got minuscule crumbs. The average slice would be dragged down by those tiny offerings. The data is pulled towards the left, by those few outliers. See the pattern? The tail tells you which way it's skewed.

The Mean, Median, and Mode Tango

So, how does this skewness actually affect our precious bell curve? Well, it throws a wrench into the works of our central tendencies: the mean, the median, and the mode. Remember how in a perfectly symmetrical normal curve, these three amigos all hang out together at the peak? They’re best buds, inseparable. But when skewness enters the picture, they start to do a little dance, each taking a different position.

In a positively skewed (right-skewed) distribution, the mean is like the adventurous one, always wanting to explore the outliers. Those extremely high values in the right tail pull the mean upwards. The median, which is the middle value when the data is ordered, is less affected by these extreme values. It’s like the sensible one, sticking to the heart of the data. And the mode, the most frequent value, will be the lowest of the three, sitting at the peak of the most common scores.

So, in a positively skewed distribution, you’ll typically find the order: mode < median < mean. The mean is the highest because those extreme high values are dragging it along for the ride. It's like our income example – the average income is higher than what most people earn because of the few billionaires.

Now, flip that around for a negatively skewed (left-skewed) distribution. Here, the extreme low values in the left tail grab hold of the mean and drag it down. The median, still the middle kid, remains relatively unbothered. The mode, being the most frequent score, will be the highest, representing the cluster of high scores.

So, in a negatively skewed distribution, the order is usually: mean < median < mode. The mean is the lowest because those extremely low scores are pulling it down. Think of that easy test scenario – the average score might be lower than what most students actually got because of those few really bad scores.

It’s a bit like a tug-of-war. The outliers are the strong guys on one end, pulling the mean in their direction. The median is the referee, staying in the middle. And the mode is the person who just keeps showing up the most, oblivious to the tug-of-war.

Why Should I Care About a Lopsided Curve?

Okay, so we've established that skewness means our bell curve isn't perfectly symmetrical. But why is this important? Is it just some abstract statistical concept we can all collectively nod about and then forget? Absolutely not! Understanding skewness is crucial because it tells us something really important about our data and what it actually represents.

For starters, it impacts our choice of the best measure of central tendency. If your data is heavily skewed, using the mean can be misleading. Imagine you're trying to describe the "typical" salary in a company with a few CEOs making millions and everyone else making a decent but standard wage. The mean salary would be astronomically high and not at all representative of what most employees actually earn. In such cases, the median is often a much better indicator of the typical value. It gives you a clearer picture of the "middle" of the data, unclouded by extreme outliers.

Also, skewness can signal underlying patterns or issues in your data collection. If you're expecting a normal distribution for something and you get a skewed one, it might be worth investigating why. Did you accidentally include an unusual group in your sample? Is there a flaw in your measurement process? Or is the phenomenon you're studying inherently skewed?

Think about customer satisfaction surveys. If most people are happy (scores clustering high) but a few are extremely unhappy (low scores), the data will be negatively skewed. This tells you that while the majority are content, there's a critical group of customers who are having a terrible experience, and you need to pay attention to them.

In fields like finance, understanding skewness is paramount. Asset returns, for instance, are often positively skewed (lots of small gains, occasional huge gains, and infrequent but potentially catastrophic losses). This is why "risk management" is such a big deal – you don't want to be caught off guard by those extreme, tail-end events.

Spotting the Lean: Visual Cues

How can you tell if your data is skewed without getting too deep into calculations? Well, visual aids are your best friend here! A histogram is a fantastic tool. If you plot your data on a histogram and it looks like a bell, you're golden. If it's leaning to one side, you've got skewness.

A box plot is another one. Remember those? They show you the median, quartiles, and potential outliers. In a skewed distribution, the "box" (representing the interquartile range) will be off-center, and the "whiskers" (the lines extending from the box) will be of unequal length. A longer whisker on one side indicates the direction of the skew.

And, of course, if you're feeling a bit more adventurous, there are statistical tests for skewness. But for everyday purposes, a good look at a histogram or box plot will usually give you a pretty good idea.

In Conclusion (But Not Really)

So, while the perfectly symmetrical normal curve is a beautiful ideal, real-world data often deviates. And that deviation, that lack of symmetry, is what we call skewness. It's not a flaw; it's a characteristic. It tells us about the distribution of our data and can significantly influence how we interpret it, especially when it comes to measures of central tendency.

Next time you encounter a distribution that doesn't look like a textbook bell curve, don't panic! Just ask yourself: which way is it leaning? Where is that long tail stretching? Because that tail, my friends, is telling you a story. A story about the outliers, the extremes, and the true nature of your data. And understanding that story is a key step in becoming a savvier data explorer. Now, go forth and analyze with your newfound understanding of lopsided curves!