Why Is 2-methyl-2-butene More Stable Than 2-methyl-1-butene

Okay, so, you ever wonder why some molecules are just, like, chiller than others? You know, more content? It’s a weird thought, right? We're talking chemistry here, not feelings. But seriously, some molecules are just… more stable. And today, we're diving into the fascinating, and maybe a little bit nerdy, world of 2-methyl-2-butene versus its slightly more… fidgety cousin, 2-methyl-1-butene. Grab your imaginary coffee, let’s chat!

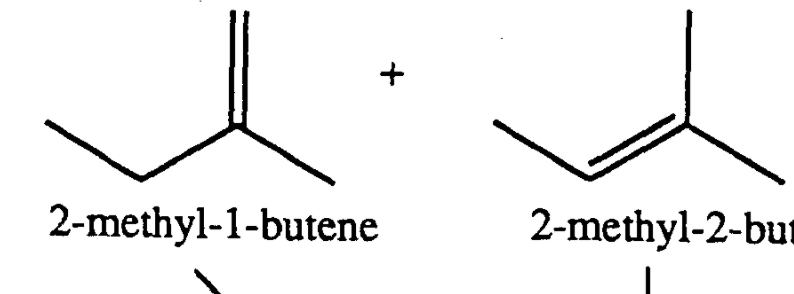

So, these two guys, right? They're isomers. That’s a fancy science word for saying they have the same recipe – same number of carbons, same number of hydrogens – but they’re put together differently. Think of it like having all the ingredients for a cake, but one is a perfectly baked loaf, and the other is… well, a slightly lopsided muffin. They’re both cake-ish, but one’s just a bit more… settled.

The big difference between these two is where their double bond is hanging out. You know, that super-reactive part of a molecule. In 2-methyl-2-butene, the double bond is smack dab in the middle, connecting two carbons that are both, like, pretty popular. It’s got friends on both sides, if you catch my drift.

But in 2-methyl-1-butene, that double bond is on the edge. It’s like it’s hanging out at a party on the far end of the dance floor, looking for attention. It’s got one carbon buddy on one side, and then… nothing but empty space on the other. Not exactly the most social situation for a double bond, is it?

This, my friends, is where the magic – or, you know, the chemistry – happens. That double bond is the key to everything. It’s the energetic hotspot, the place where all the action occurs. And how it’s positioned makes a world of difference in how happy, or stable, the molecule is.

So, why is the middle-of-the-road double bond in 2-methyl-2-butene so much more stable? It all comes down to something called hyperconjugation. I know, I know, sounds like a superhero move, right? "It's hyperconjugation to the rescue!" But it’s actually way cooler, in a subtle, molecular kind of way.

Hyperconjugation is basically this phenomenon where the electrons in the bonds around the double bond can kind of… share their love. They extend their electron clouds and overlap a little with the pi electrons of the double bond. Think of it like having extra hands helping out. The more hands you have, the more support you get, right?

In 2-methyl-2-butene, that double bond is attached to two carbon atoms. And each of those carbons has other carbon atoms and their hydrogen buddies attached to them. These adjacent C-H bonds, they’re perfectly positioned to offer up their electrons to the double bond. It's like a big, supportive family reunion.

Specifically, the carbon that is part of the double bond and also attached to the methyl group (that’s the CH3 thingy) has two C-H bonds on its methyl group. And the other carbon of the double bond? It’s attached to another methyl group, which also has two C-H bonds. So, you've got a total of four C-H bonds that can participate in this electron-sharing party. That's a lot of helping hands!

These C-H bonds are adjacent to the double bond. And the electrons in these C-H sigma bonds can overlap with the empty antibonding pi orbital of the double bond. It's like a gentle caress of electrons, spreading out the electron density and, crucially, lowering the energy of the whole molecule. Lower energy means more stability. It's like a molecule taking a deep, relaxing breath.

Now, let’s look at our friend, 2-methyl-1-butene. Remember how that double bond is on the end? It’s connecting a carbon that has two hydrogens attached to it, and a carbon that has a methyl group attached to it. It’s a bit of a lonely situation for that double bond.

The double bond in 2-methyl-1-butene is between C1 and C2. C1 has two hydrogens. C2 has the methyl group. So, only the C-H bonds on the methyl group are adjacent to the double bond. That methyl group has three C-H bonds. So, we have three sets of C-H sigma bonds that can potentially overlap with the double bond's pi system.

See the difference? 2-methyl-2-butene has four sets of adjacent C-H bonds contributing to hyperconjugation. 2-methyl-1-butene only has three. It’s not a huge difference in number, but in the delicate world of molecular stability, every little bit counts. It’s like the difference between a good hug and a pat on the shoulder. Both are nice, but one is definitely more… encompassing.

So, the more hyperconjugation you have, the more the electron density is spread out. This reduces the electron-electron repulsion within the double bond, making it less eager to react. It’s like having a more distributed load, so no single point is under too much stress. The molecule is just more… at ease.

Another way to think about it is through the lens of electrophilic addition. Alkenes, with their double bonds, are like magnets for electrophiles – things that are electron-loving. They’re drawn to that electron-rich double bond like moths to a flame. But the strength of that attraction, and how easily the molecule reacts, is influenced by its stability.

When an electrophile, let's call it "E+", approaches an alkene, it’s going to attack the double bond. This forms a carbocation intermediate. And carbocations? They’re notoriously unstable. They’re like teenagers who have just been told they can't go to the party – a bit frantic and wanting to stabilize themselves ASAP.

The stability of that carbocation intermediate is hugely important. And guess what stabilizes carbocations? You guessed it – hyperconjugation! Alkyl groups attached to the positively charged carbon atom can donate electron density through hyperconjugation, making that positive charge less intense and therefore more stable.

Let's look at the carbocation formed when E+ adds to 2-methyl-1-butene. The double bond breaks, and E+ attaches to the terminal carbon (C1). This leaves the positive charge on C2. So, you get a tertiary carbocation. This carbon (C2) is attached to the methyl group and two other carbons (which are part of the original double bond, but now single-bonded). So, the positive charge is on a carbon bonded to three other carbons. That’s a tertiary carbocation.

Now, consider the carbocation formed when E+ adds to 2-methyl-2-butene. The double bond breaks, and E+ can add to either of the carbons that were part of the double bond. Let's say it adds to C2. Then the positive charge is on C3. Oops, wait. Let me re-draw that. The double bond is between C2 and C3 in 2-methyl-2-butene. So, if E+ adds to C2, the positive charge is on C3. C3 is attached to one methyl group and one other carbon (C2, which is now single-bonded). This would be a secondary carbocation. Hmm, this is getting confusing. Let's use the standard numbering.

Let's restart the carbocation part for clarity. The parent chain is four carbons. So we have butene. The double bond is the key. In 2-methyl-1-butene: The double bond is between C1 and C2. The methyl group is on C2. So, CH2=C(CH3)-CH2-CH3. If an electrophile (E+) attacks the double bond, it will go to the carbon with more hydrogens to form the more stable carbocation (Markovnikov's rule). So E+ goes to C1. This leaves the positive charge on C2. C2 is attached to the methyl group and two other carbons (C3 and C4). This is a tertiary carbocation: E-CH2-C+(CH3)-CH2-CH3. Tertiary carbocations are generally quite stable because the positive charge can be delocalized onto three adjacent alkyl groups through hyperconjugation.

In 2-methyl-2-butene: The double bond is between C2 and C3. The methyl group is on C2. So, CH3-C(CH3)=CH-CH3. If an electrophile (E+) attacks this double bond, it can go to C2 or C3. If it goes to C3, the positive charge will be on C2. C2 is attached to two methyl groups and one other carbon (C3, now single-bonded). This results in a tertiary carbocation: CH3-C+(CH3)(CH3)-CH2-CH3. This is also a tertiary carbocation. Wait, they both form tertiary carbocations? What’s going on? This is where it gets tricky and requires a bit more precision.

Let's re-evaluate the structure and the hyperconjugation in each case. For 2-methyl-1-butene: CH2=C(CH3)-CH2-CH3. The double bond is between C1 and C2. The methyl group is on C2. When E+ adds to C1, the carbocation is on C2: E-CH2-C+(CH3)-CH2-CH3. The positively charged carbon (C2) is attached to the methyl group, and the ethyl group. So it's a tertiary carbocation, and it has three alpha hydrogens on the methyl group and two alpha hydrogens on the ethyl group. So, 5 alpha hydrogens available for hyperconjugation that stabilize the carbocation.

For 2-methyl-2-butene: CH3-C(CH3)=CH-CH3. The double bond is between C2 and C3. The methyl group is on C2. When E+ adds to C3, the carbocation is on C2: CH3-C+(CH3)(CH3)-CH2-CH3. The positively charged carbon (C2) is attached to two methyl groups and the ethyl group. So, it's a tertiary carbocation. It has three alpha hydrogens on the first methyl group, three alpha hydrogens on the second methyl group, and two alpha hydrogens on the ethyl group. That makes a total of 3 + 3 + 2 = 8 alpha hydrogens available for hyperconjugation!

Aha! There’s the key difference. While both can form tertiary carbocations, the 2-methyl-2-butene pathway leads to a carbocation that is stabilized by more hyperconjugation. More hyperconjugation means the carbocation is more stable, which means the reaction proceeds more easily, and the starting alkene is more stable (because it's less eager to react and form something unstable).

So, in essence, the double bond in 2-methyl-2-butene is like a well-insulated house. It’s got all these extra electron-donating groups (the alkyl groups) cozying up to it, sharing their warmth and making it feel secure. The double bond in 2-methyl-1-butene is more like a slightly drafty cottage. It’s got some insulation, sure, but not as much, making it a bit more susceptible to the elements – or, in chemistry terms, to reactive species.

This stability difference isn't just a theoretical nicety. It has real-world implications. For instance, in reactions like hydrogenation (adding hydrogen across the double bond), the more stable alkene will react more slowly. It takes more energy to “break apart” that stable molecule. Think of trying to convince a really content person to go on a wild adventure versus someone who’s already a bit bored.

Also, in processes like cracking petroleum, where you break down larger hydrocarbons, the relative stabilities of different alkenes can influence which products are formed. It’s all about following the path of least resistance, or in this case, the path of greatest stability.

So, the next time you're looking at these two molecules, remember: it’s all about that double bond placement. The more substituted the double bond is with alkyl groups (meaning, the more carbons are directly attached to the carbons of the double bond), the more hyperconjugation you get, the more stable the molecule. 2-methyl-2-butene has a double bond between two tertiary carbons (if you consider the carbons that are part of the double bond). Wait, that's not quite right. Let's focus on the carbons directly attached to the double bond carbons. In 2-methyl-2-butene, the double bond is between C2 and C3. C2 is attached to a methyl and another carbon. C3 is attached to one carbon. So C2 is a disubstituted carbon and C3 is a monosubstituted carbon involved in the double bond. No, this is where my analogy might be getting muddled.

Let's go back to the number of alkyl groups directly attached to the carbons of the double bond. In 2-methyl-1-butene: CH2=C(CH3)-CH2-CH3. The double bond is between C1 and C2. C1 has zero alkyl groups attached. C2 has one alkyl group (the methyl group) directly attached. So, we have a total of one alkyl group directly attached to the carbons of the double bond. This is called a monosubstituted alkene (considering the carbon with no alkyl groups as less substituted than the one with one, or you could say C1 is unsubstituted and C2 is substituted. It's often classified as a disubstituted alkene when considering the groups on both sides of the double bond. Let's clarify the nomenclature and substitution.

The general rule is: the more substituted the alkene, the more stable it is. Substitution refers to the number of alkyl groups attached to the carbons involved in the double bond. For 2-methyl-1-butene: CH2=C(CH3)-CH2-CH3. The double bond is between C1 and C2. C1 has two H atoms attached. C2 has one CH3 group and one CH2CH3 group attached. So, there are two alkyl groups attached to the carbons of the double bond (one methyl and one ethyl on C2). Therefore, it's a disubstituted alkene.

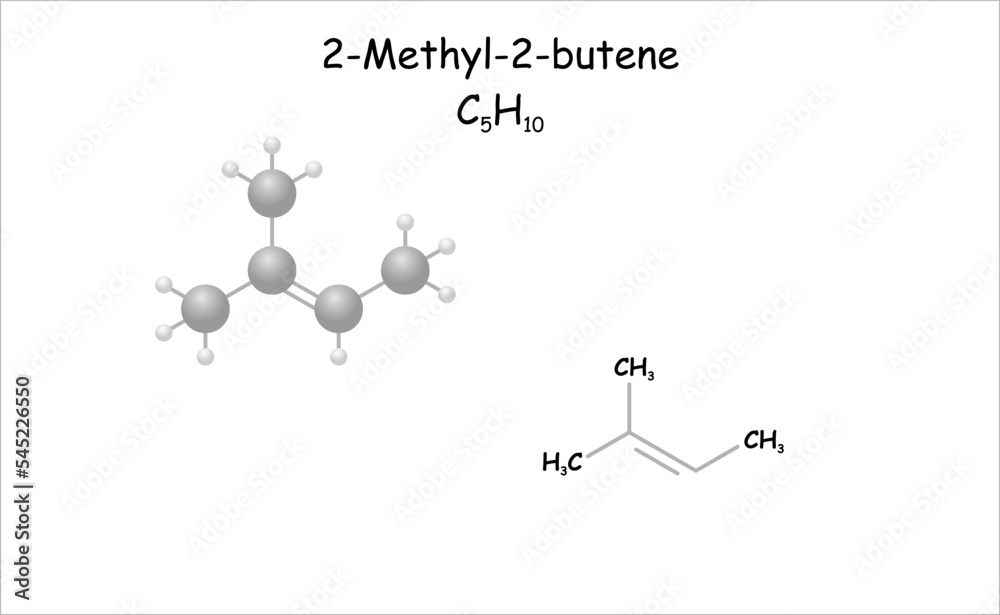

For 2-methyl-2-butene: CH3-C(CH3)=CH-CH3. The double bond is between C2 and C3. C2 has one CH3 group and another CH3 group attached. C3 has one H atom and one CH3 group attached. So, there are three alkyl groups attached to the carbons of the double bond (two methyls on C2 and one methyl on C3). Therefore, it's a trisubstituted alkene.

So, 2-methyl-2-butene is a trisubstituted alkene, and 2-methyl-1-butene is a disubstituted alkene. Since trisubstituted alkenes are generally more stable than disubstituted alkenes, this is another way to understand why 2-methyl-2-butene is the more chill one.

This general trend of alkene stability holds true: tetrasubstituted > trisubstituted > disubstituted > monosubstituted > ethene. The increased substitution provides more opportunities for hyperconjugation, which stabilizes the electron system of the double bond. It’s like having more cushions on your couch – the more cushions, the comfier and more stable you are.

So, it boils down to this: more alkyl groups attached to the double bond = more hyperconjugation = more electron density delocalization = lower energy = greater stability. It’s a beautiful cascade of chemical goodness!

And that, my friends, is why 2-methyl-2-butene is just a little bit more relaxed, a little bit more content, a little bit more… stable than its isomer, 2-methyl-1-butene. It's all about those electron-donating buddies hanging out near the party! Pretty neat, huh? Chemistry is full of these little secrets, just waiting to be uncovered. Now, who wants another cup of this imaginary coffee?