Which Of The Following Would Not Contribute To Allopatric Speciation

Hey there, curious minds! Ever wondered how we got so many amazing and sometimes downright weird creatures on our planet? It's like a giant, ongoing party of evolution, and today we're going to peek at one of its really cool party tricks: allopatric speciation!

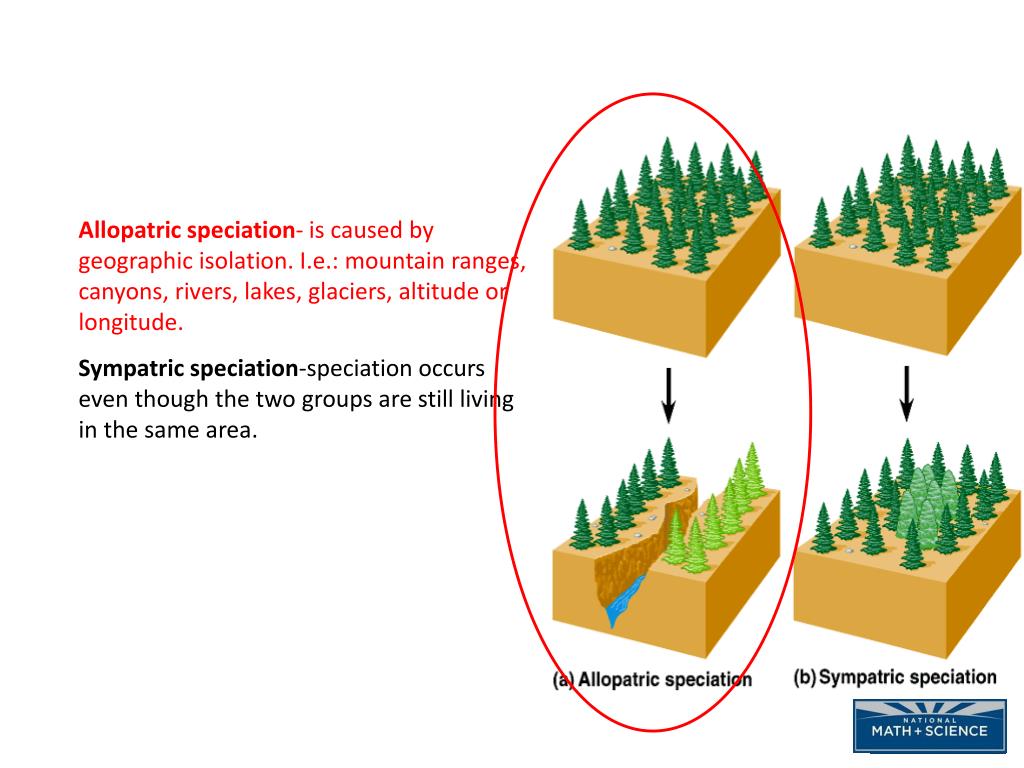

Think of it like this: imagine a bunch of fuzzy little critters living happily in their cozy little neighborhood. Then, BAM! A big ol' mountain range pops up, or a giant river starts flowing right through their turf. Suddenly, these critters are split into two groups.

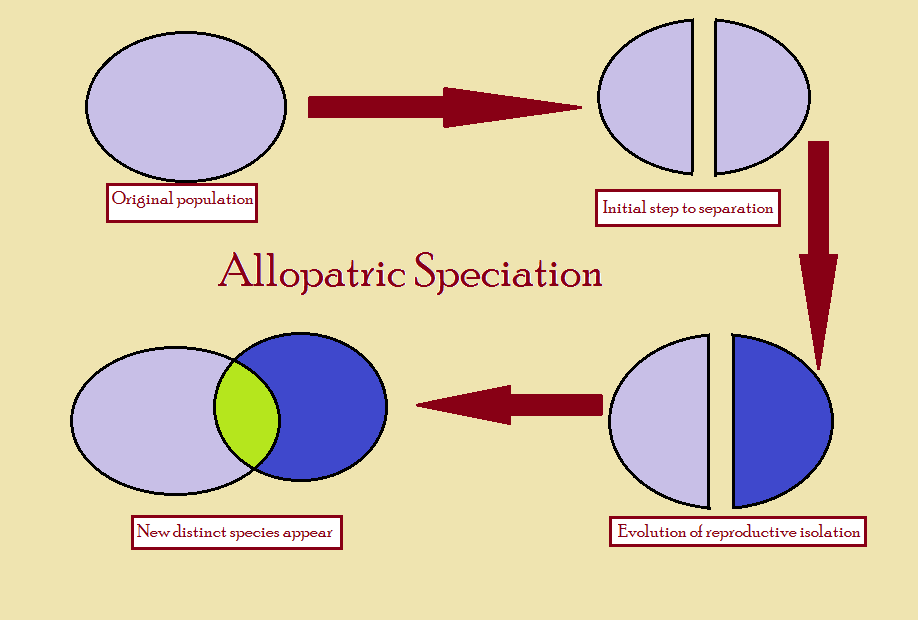

This splitting is the first step in a fascinating process. The groups are now separated, living their own separate lives. Over time, these separated groups start to change, becoming more and more different from each other. It's like they're playing a really, really long game of evolutionary telephone!

Eventually, these groups might become so different that if they ever met again, they wouldn't want to hang out. They wouldn't be able to have little critter babies together anymore. And guess what? That's when a new species is born! Pretty neat, right?

Now, to really get our heads around this awesome speciation party, let's talk about what doesn't get an invitation to the allopatric speciation bash. It's like trying to figure out who forgot to bring the party hats! We're going to look at a few scenarios and see which one is just not contributing to this grand evolutionary event.

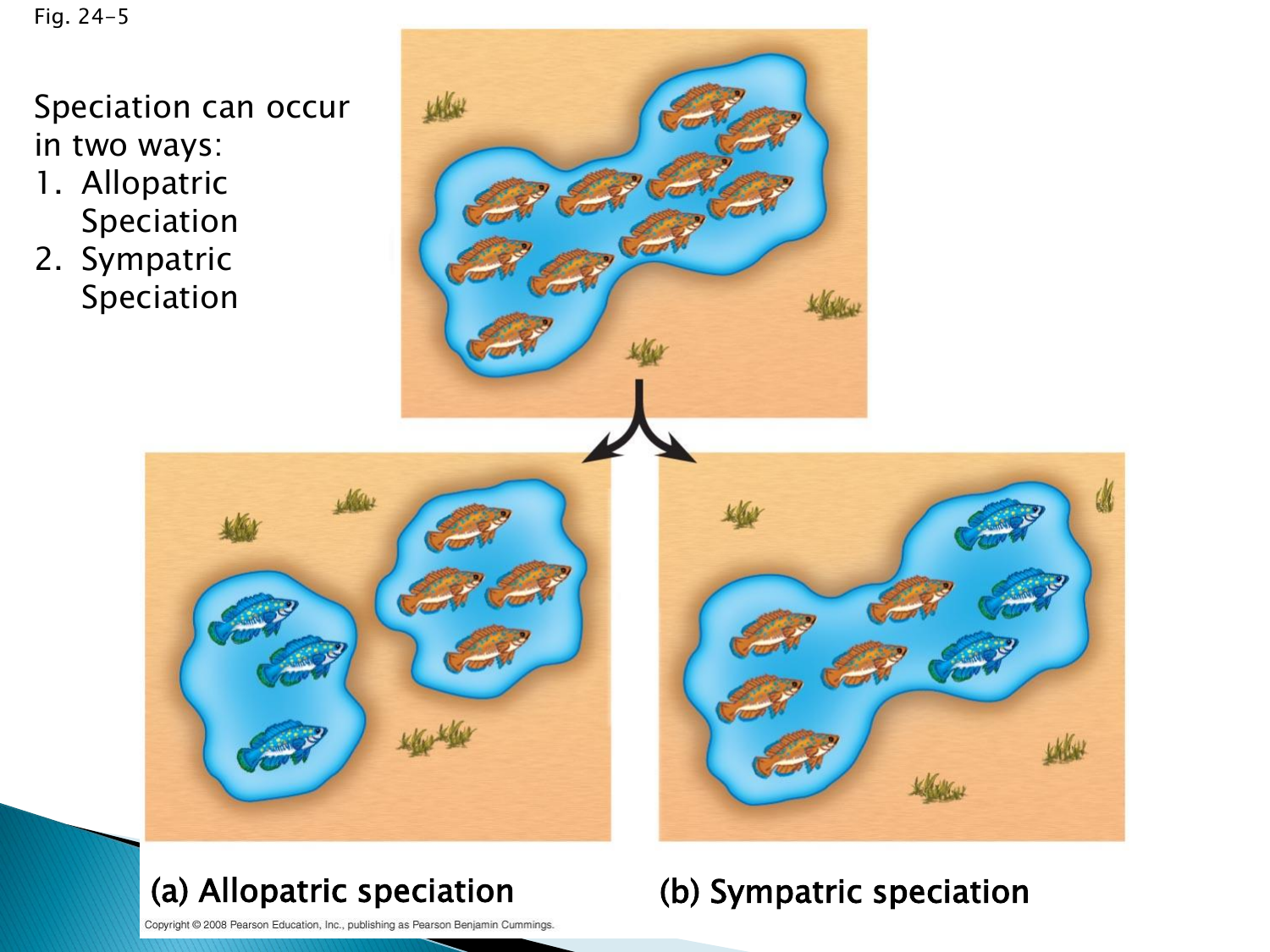

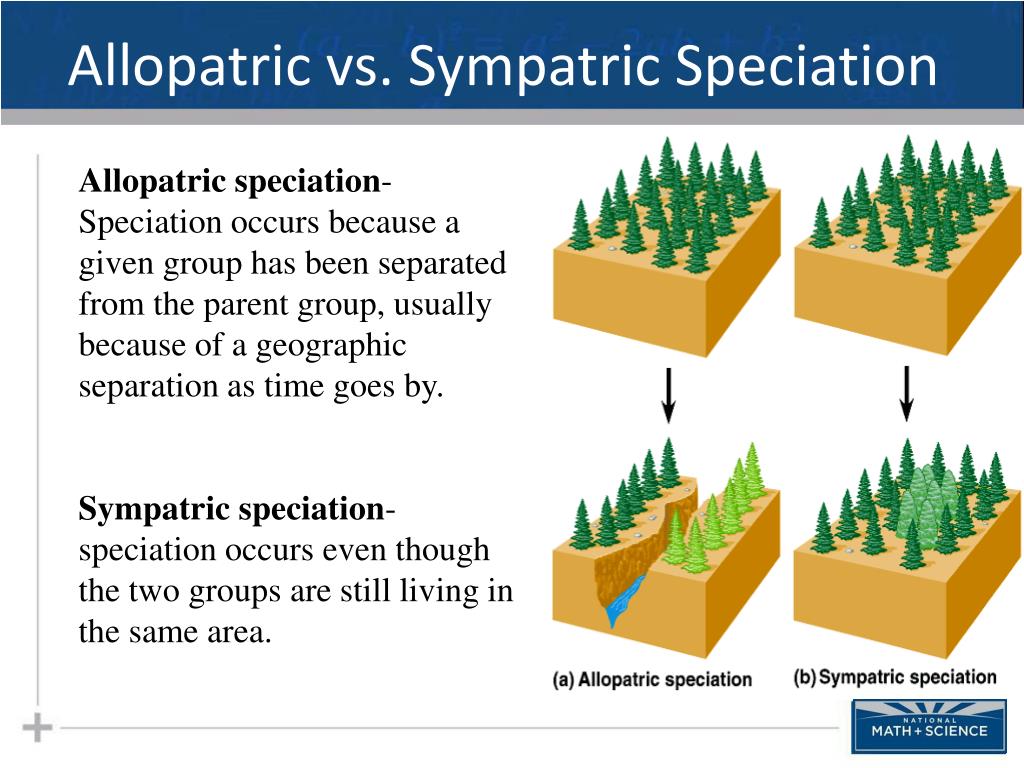

So, what exactly is allopatric speciation? The name itself gives us a clue. "Allo" means "other" or "different," and "patric" relates to "homeland" or "country." So, it’s speciation that happens when groups are in different homelands – literally separated by geography.

The key ingredients for allopatric speciation are a physical barrier and enough time for the separated populations to diverge. Think of islands, mountains, deserts, or even just a really wide road. These things act as the ultimate party poopers for gene flow between the groups.

Now, let's get to the fun part: what wouldn't help this separation happen? Imagine a scenario where our critter groups are still able to mingle. Even if they’re a little bit apart, if they can still cross over and say "howdy" to each other, then they're not really being allopatrically separated.

One of the things that wouldn't contribute to allopatric speciation is if the populations remain in constant and easy contact. If they can still easily find each other, mate, and have offspring, then they’re essentially one big, happy, gene-sharing family. No new species popping into existence in this case!

Think about two groups of birds living on opposite sides of a very wide but very flat plain. If the birds can fly anywhere they please, and they still see each other as potential mates, then the plain isn't acting as a significant barrier. They’re not truly separated enough for allopatric speciation to kick in.

Another thing that would not help is if the geographical barrier is not permanent or is easily overcome. If a river that separates two groups dries up every summer, allowing the critters to wander back and forth, then the separation isn't strong enough. It’s like a revolving door for genes!

Consider a population of fish separated by a shallow stream. If a good rain can turn that stream into a raging river, but then it recedes, allowing for gene flow, that’s not a solid barrier. The fish can still mix and mingle when conditions are right. This keeps them from becoming distinct, separate species.

It's all about that magical disconnect! The barrier needs to be good enough to keep the gene pools from mixing significantly. If the groups can still exchange genes freely, they’re essentially staying on the same evolutionary track. It’s the lack of gene flow that allows for divergence.

So, what would contribute? A strong, undeniable barrier! Think of the Grand Canyon. It’s not exactly easy for a squirrel to just scamper across that! Or the vast Pacific Ocean separating island populations. Those are serious separators!

Another factor that definitely helps is time. Evolution isn't usually an overnight sensation. It takes ages for populations to accumulate enough genetic differences to become truly separate species. So, a short separation might not be enough.

The longer the isolation, the more chances for mutations to arise and spread within each population independently. Different environments can also put different pressures on each group, selecting for different traits. It’s a slow and steady race to new species!

Imagine two colonies of ants separated by a mountain range for thousands of years. Over that immense period, they might develop totally different social structures, pheromones, and even physical characteristics. They'd be like cousins who grew up on different continents and barely recognize each other!

So, to recap our "who's not invited" list for allopatric speciation: anything that keeps the populations in continuous and easy contact. Anything that makes the geographical barrier weak or temporary. These are the things that would prevent the magic from happening.

The core idea is that the separation itself is the star of the show for allopatric speciation. If the groups aren't truly separated, or if the separation isn't lasting enough, then the evolutionary divergence needed to create new species just won't occur. It’s like trying to bake a cake without a solid oven – the ingredients are there, but the conditions aren't right!

It’s a beautiful dance of isolation and adaptation. The environment plays a big role, of course. If one group ends up in a desert and the other in a lush forest, they’ll face different challenges and evolve different solutions. This environmental pressure accelerates the divergence.

Think about the famous Darwin's finches on the Galápagos Islands. Each island had slightly different food sources, leading to finches with different beak shapes. These islands acted as their separate homelands, and over time, the finches on each island became distinct.

So, when we look at a question about what would not contribute to allopatric speciation, we're essentially looking for something that maintains gene flow between populations or prevents a lasting geographical separation. We want the opposite of isolation!

It’s like trying to keep two toddlers from playing together if they’re in the same room with all their favorite toys. If they can easily interact and share, they're not going to develop into completely separate entities. The same principle applies to species!

The whole concept is so fascinating because it shows us how dynamic life on Earth is. It’s not just static; it’s constantly changing, evolving, and branching out. Allopatric speciation is one of the major engines driving this incredible biodiversity.

So next time you see a river or a mountain, you can imagine it as a potential stage for a future speciation event! It’s a reminder of the power of geography and the slow, steady march of evolution. It’s nature’s way of throwing a party and inviting new guests to the evolutionary ball!

We're basically looking for the factors that keep our critter populations interconnected rather than isolated. The less interconnected they are, the more likely they are to become distinct species over time. It's a beautiful illustration of how separation can lead to novelty.

This process highlights the importance of geographical barriers, not just as physical obstacles, but as facilitators of genetic divergence. Without those barriers, the evolutionary paths of populations tend to stay intertwined. It's the separation that allows for independent evolution to take hold.

So, to sum it up with a smile, we're looking for the thing that says, "Nope, these groups are still totally buddy-buddy and can easily swap genes!" That's the one that doesn't get a ticket to the allopatric speciation party. Happy exploring the wonderful world of evolution!