Which Of The Following Statements About Oligopolies Is Not Correct

So, picture this: my neighbor, bless his heart, is absolutely obsessed with his lawn. I mean, we're talking military precision with the mower, the fertilizer applications are timed with a stopwatch, and he’s got a special sprinkler system that I’m pretty sure uses GPS. It's a beautiful lawn, I'll give him that. But there’s only really one other guy on our street who even attempts to keep up with him in the lawn-care Olympics. The rest of us? We do our best, but it’s kind of like a two-horse race, right? We know what the super-lawn guy is doing, and the other guy knows, and that influences what they do. It’s a weird little ecosystem, and it got me thinking about business ecosystems.

Specifically, it got me pondering those situations where it's not just one giant company running everything (that's a monopoly, super boring and often kind of evil), and it's not a bazillion tiny ones all scrambling for scraps (that's perfect competition, also kind of boring from a strategic point of view). No, I’m talking about the middle ground: oligopolies. You know, those markets dominated by a small number of large firms. Think of the airlines, the major mobile carriers, or even, dare I say it, those massive tech giants. It’s where things get… interesting. And sometimes, a little bit… tricky.

Now, this whole oligopoly thing is a favorite topic for economists. They love to dissect it, break it down, and then, inevitably, present you with a bunch of statements and ask, "Which of these is not correct?" It’s like a pop quiz, but instead of embarrassing yourself in front of your classmates, you’re just trying to impress your own internal economist. And let’s be honest, who doesn’t want to impress their internal economist? They’re the ones who really get how the world works, or at least, how it should work.

The "Us vs. Them" Mentality of Oligopolies

The defining characteristic of an oligopoly is that few firms dominate the market. And when I say few, I mean really few. So few that the actions of any one firm can significantly impact the others. It’s like if I decided to sell my soul for a perfect lawn; my neighbor would definitely notice and probably ramp up his fertilizer game. This interdependence is the name of the game. They’re not operating in a vacuum. They’re constantly watching each other, anticipating each other’s moves, and reacting. It’s a bit like a chess match, but with really high stakes and often, with slightly less predictable moves than a grandmaster.

This interdependence often leads to some pretty fascinating behaviors. For example, firms in an oligopoly might engage in price wars. Imagine two mobile carriers deciding to slash their prices to grab market share. It’s great for us consumers for a while, right? Cheaper phones! But for the companies, it’s like a brutal brawl. They might eventually realize that this constant price cutting just hurts everyone’s profits. So, what happens next? Often, they might, ahem, implicitly or explicitly collude to keep prices higher. This isn't always as nefarious as it sounds – sometimes it’s just about recognizing that stability is better for everyone involved. But it can definitely feel like they’re all holding hands and singing kumbaya while we pay through the nose.

And then there’s non-price competition. If slashing prices is too risky (or too obviously anti-consumer), what else can they do? They can try to differentiate their products. Think about all those fancy features your phone has. Or the different classes of seats on an airplane. Or the loyalty programs that try to bribe you into sticking with them. These are all ways for oligopolistic firms to compete without directly attacking each other on price. It’s a bit like my neighbor investing in a robot mower instead of just buying more grass seed. It’s a different kind of arms race, really.

Common Misconceptions: What Oligopolies Are NOT

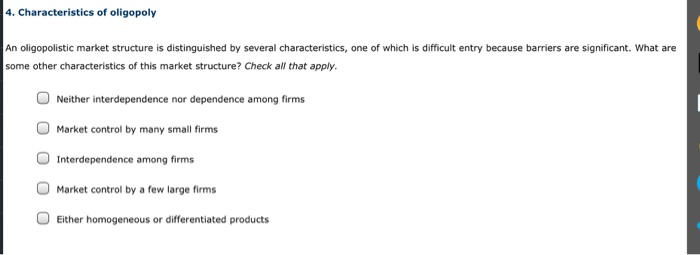

Now, here’s where things get tricky, and where those quiz questions often try to trip you up. We need to understand what makes an oligopoly an oligopoly and what makes it something else entirely. Let’s take a look at some statements and see if they hold water.

Statement 1: Firms in an oligopoly face significant barriers to entry.

This one is generally correct. Think about it: if it were easy for new companies to pop up and challenge the big players in, say, the smartphone operating system market, it wouldn’t be an oligopoly for long, would it? These barriers can be many things: massive capital requirements (you need billions to build a new car company, folks!), established brand loyalty (we’re all a bit addicted to our iPhones or Galaxies), patents and technology, or even just the sheer scale of existing operations. These barriers act like a really sturdy fence, keeping new competitors out. So, yeah, this statement is usually spot on.

Statement 2: Firms in an oligopoly typically produce standardized products.

Okay, this is where it starts to get a little wobbly. While some oligopolies do produce standardized products (think oil, for instance, where crude oil from one refinery is pretty much the same as crude oil from another), many, many oligopolies involve differentiated products. We talked about this with non-price competition. Apple's iPhone is not the same as Samsung's Galaxy, even though they serve a similar purpose. They’re differentiated through design, software, marketing, and all sorts of other bells and whistles. So, saying they typically produce standardized products? That’s a bit of a stretch. This statement is leaning towards being incorrect.

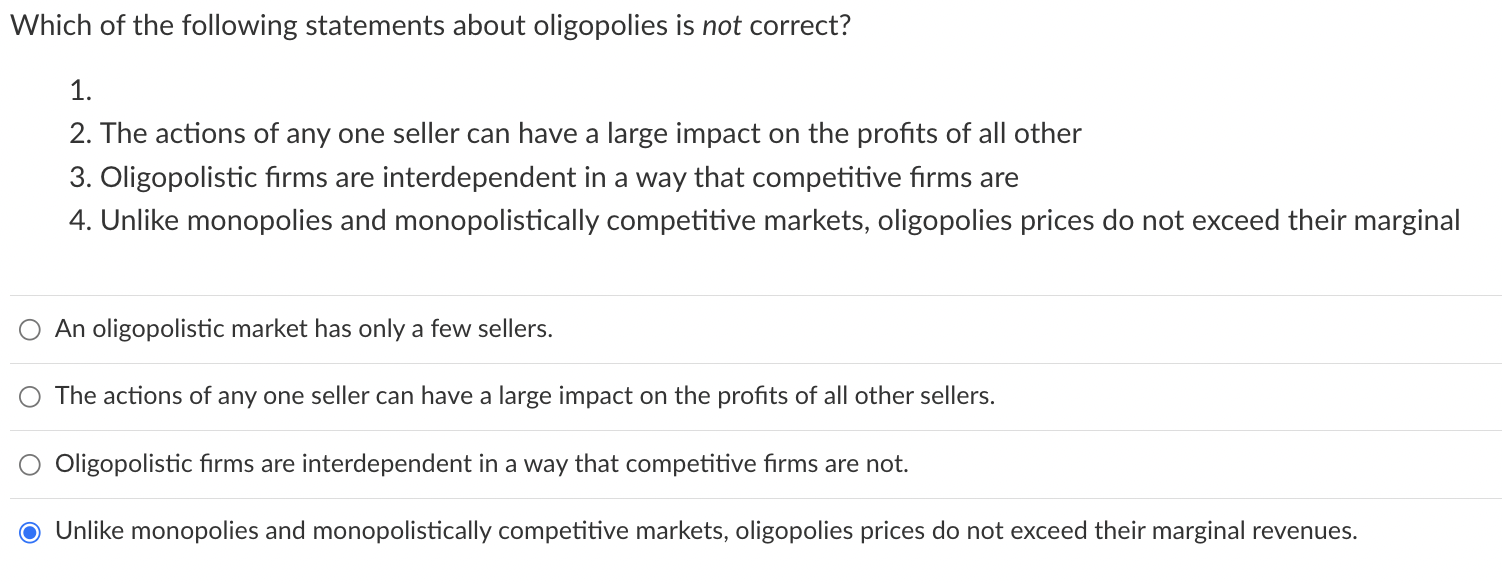

Statement 3: Firms in an oligopoly are highly interdependent, meaning their decisions significantly affect each other.

Yep, this is the big one. As we discussed, this is the core of what an oligopoly is. If one of the three major airlines decides to offer a massive fare sale, the other two are going to feel it in their wallets, and they’ll have to respond. This interdependence is what makes oligopolies so fascinating and often so challenging to analyze. It’s not as simple as just looking at what’s best for one company in isolation. You have to consider what everyone else is going to do. This statement is absolutely correct.

Statement 4: Firms in an oligopoly may engage in tacit collusion to maintain higher prices.

This is also generally correct. Tacit collusion means that firms, without explicitly agreeing, tend to follow certain pricing patterns that benefit them all. For example, if one firm raises its prices, others might follow suit. Or they might all stick to a similar pricing structure for similar services. It's not always illegal, but it definitely can feel like they're all playing nice to keep us paying more. It's less about a secret handshake and more about a shared understanding of how the game is played to maximize collective profits. Think of it like my two lawn-obsessed neighbors. They might not talk about how much fertilizer to use, but they both see the other’s impressive results and adjust their own strategy accordingly to stay competitive, rather than engaging in a race to the bottom on grass length.

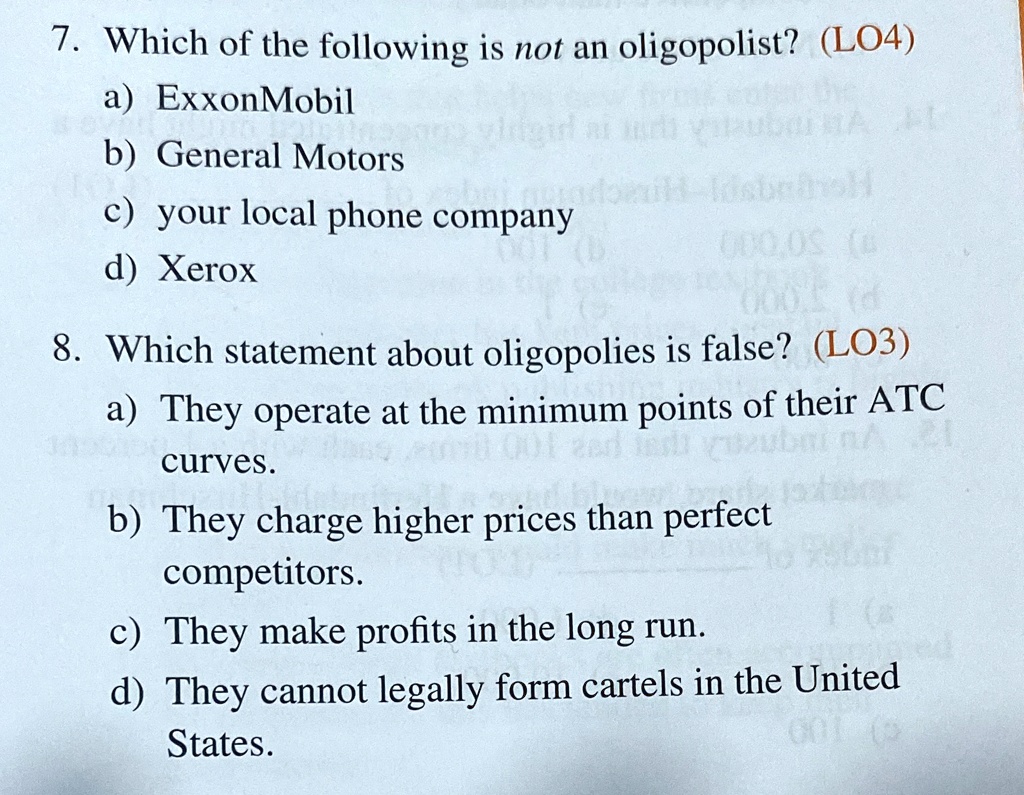

Statement 5: Firms in an oligopoly always engage in explicit collusion, such as forming cartels.

Now, this is where we hit a big, fat NOT CORRECT. While explicit collusion can happen in oligopolies (and it’s usually illegal!), it's by no means a universal characteristic. Cartels, like OPEC for oil producers, are a form of explicit collusion where firms formally agree to fix prices, output, or market share. However, these are often difficult to maintain because there's always an incentive for one member to cheat and undercut the others to gain a bigger slice of the pie. Most of the time, especially in developed economies with strong antitrust laws, explicit collusion is either rare, short-lived, or happening under the radar. Tacit collusion is much more common. So, the word "always" here is a huge red flag. This statement is definitively incorrect.

So, Which One is the Imposter?

Let’s recap the usual suspects and see which one is the odd one out, the statement that just doesn’t fit the oligopoly mold.

The Usual Suspects in Oligopoly Land

We've established that oligopolies are characterized by:

- A small number of large firms dominating the market.

- High barriers to entry, making it difficult for new firms to enter.

- Interdependence among firms, where each firm's decisions affect the others.

- Potential for price wars or, conversely, collusion (both tacit and explicit).

- Non-price competition as a key strategy.

Now, let's go back to our statements and pinpoint the incorrect one. Based on our discussions:

The statement that is NOT correct about oligopolies is often one that:

- Claims they always engage in explicit collusion.

- Suggests they only produce standardized products.

- Implies a lack of interdependence between firms.

- Downplays or ignores the existence of barriers to entry.

If we had to pick one as the most consistently incorrect, it would likely be one that makes an absolute claim where nuance is required. For instance, the idea that they always engage in explicit collusion is a classic incorrect statement. As we discussed, explicit collusion is difficult, often illegal, and certainly not the only way firms in an oligopoly behave. Tacit collusion and vigorous, non-collusive competition are also very much on the table.

Another contender for "not correct" could be the statement that firms in an oligopoly typically produce standardized products. While some do, many of the most prominent examples (like tech, auto, or soft drinks) are characterized by heavy product differentiation. So, "typically" producing standardized products is a generalization that doesn't hold up across the board.

Ultimately, when you see a question asking which statement is not correct about oligopolies, look for the one that makes an overly broad, absolute, or contradictory claim. The beauty (and sometimes the frustration) of economics is that real-world markets are complex. What's true for one oligopoly might not be true for another. But there are core principles that define them, and statements that violate those core principles are usually your incorrect answers.

So next time you're stuck on an economics quiz, or just pondering why your phone bill seems perpetually high, remember the interdependence, the barriers, and the constant strategic dance of the few powerful players in the market. It’s a lot like watching your neighbors meticulously sculpt their lawns, just with a lot more zeroes involved.