Which Of The Following Rational Functions Is Graphed Below Apex

You know, I was staring at this graph the other day, the kind that looks like a couple of squiggly lines doing their own thing in a coordinate plane. It reminded me of this one time I was trying to explain to my nephew what a “rational function” was. He’s like, ten, and his eyes just glazed over. I tried to use analogies, you know, like “it’s like a recipe where you can’t divide by zero” or “it’s like trying to pour water into a funnel that gets narrower and narrower.” He just blinked. Then I showed him a graph, and he was like, “Oh! It looks like a smiley face that’s been broken in half!” And honestly? That’s not a bad way to think about it. So, when I saw this particular graph, I thought, “Okay, little nephew, this one’s for you. Let’s see if we can figure out what kind of broken smiley face we’re dealing with here.”

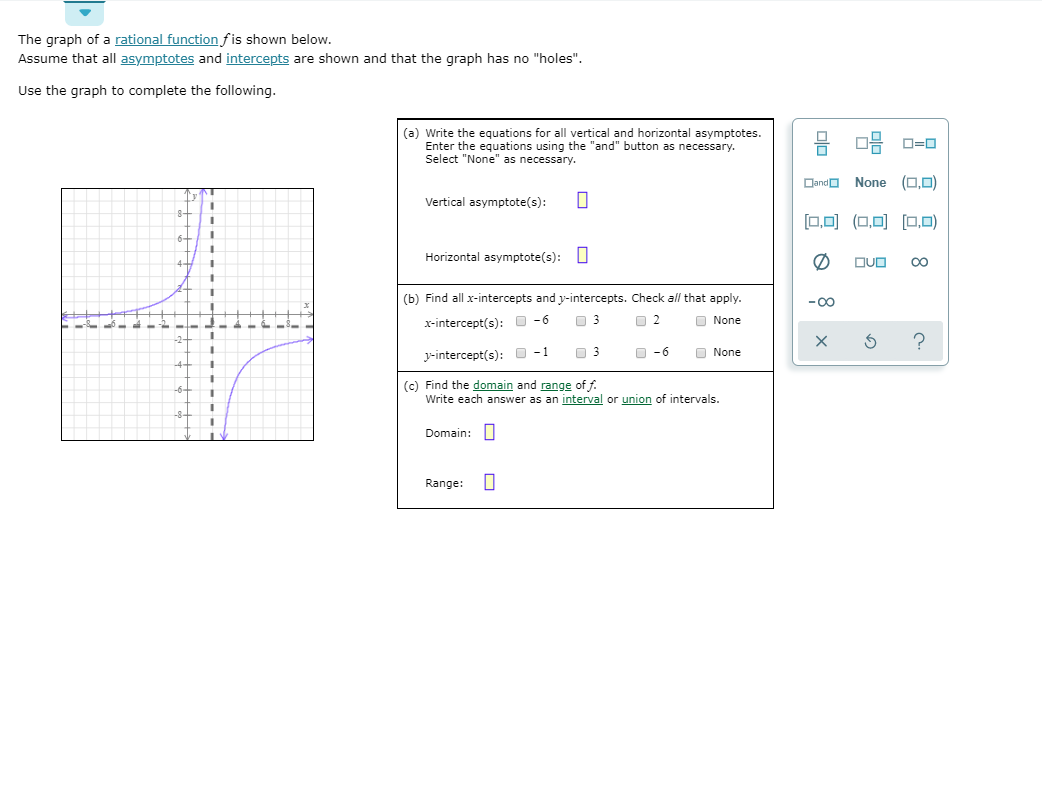

We’re presented with a visual puzzle, a graphical representation of a rational function, and our mission, should we choose to accept it (and let’s be real, we’re already here, so we’re accepting), is to identify which of the given rational functions actually produced this image. It’s like being a detective, but instead of fingerprints and alibis, we’re looking for asymptotes and holes. Pretty neat, right?

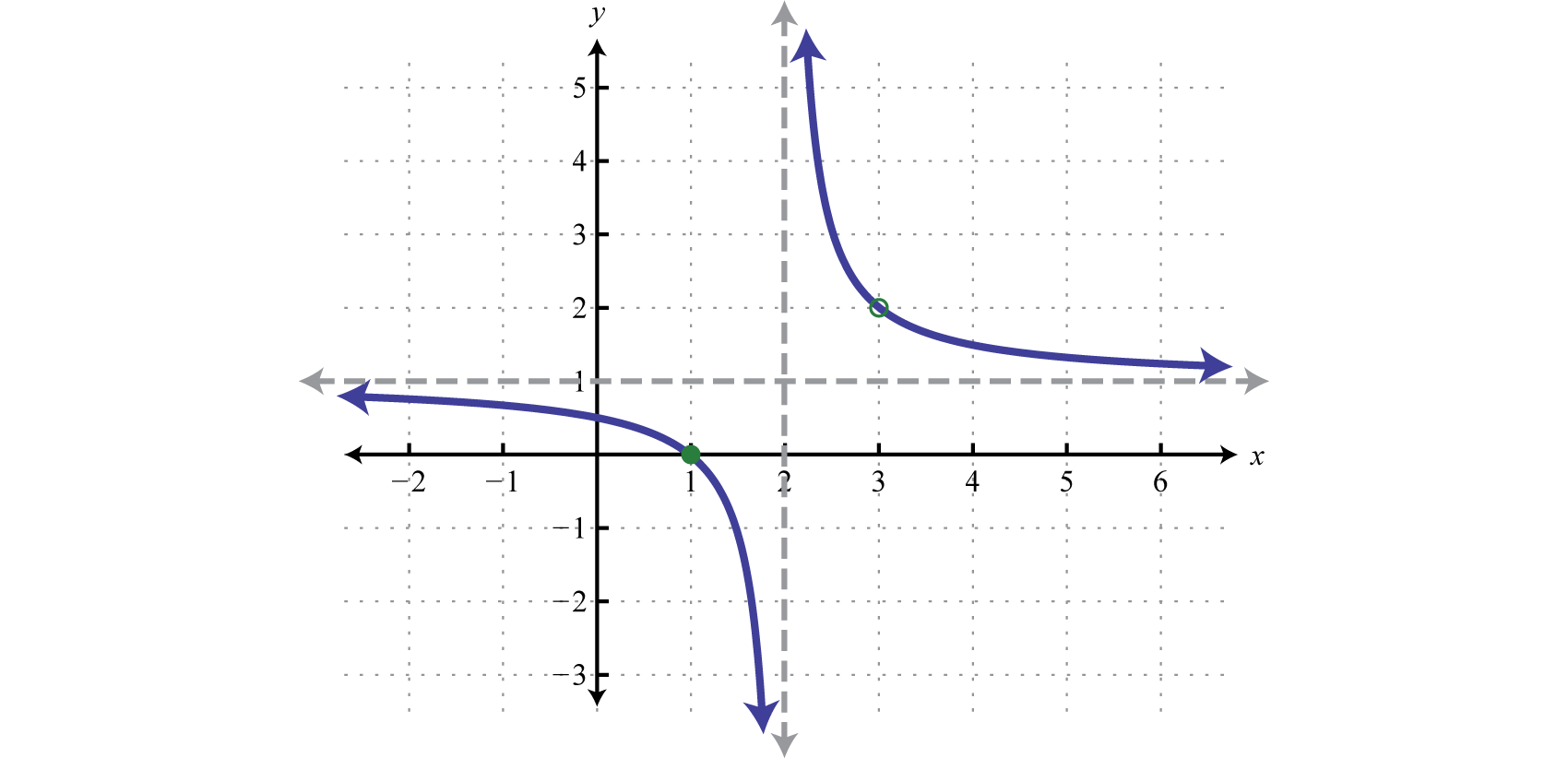

Let’s get our detective hats on. The first thing that jumps out at me when I look at this graph are those vertical lines that the squiggles seem to get really, really close to, but never actually touch. These are our vertical asymptotes. Think of them as invisible walls. The function just can’t cross them. And where do these invisible walls usually pop up? Well, for a rational function, which is basically a fancy fraction where the top and bottom are polynomials, vertical asymptotes typically show up where the denominator is equal to zero. But, and this is a big but, only if the numerator isn't also zero at that same point. If both are zero, you might have a "hole" instead, which is like a tiny, invisible dot missing from the line. We’ll get to holes later, but for now, let’s focus on these solid-looking asymptotes.

So, looking at our graph, I can see a vertical asymptote at x = -2 and another one at x = 3. This means that the denominator of our rational function, when set to zero, should give us these x-values. If we think about factoring, this suggests our denominator should have factors of (x + 2) and (x - 3). So, a likely candidate for our denominator would be something like (x + 2)(x - 3). Let’s expand that out just to see what it looks like: x² - 3x + 2x - 6, which simplifies to x² - x - 6. Keep that in your mental notepad, because it’s going to be important.

Now, let’s talk about the horizontal asymptote. See that squiggly line way up at the top and way down at the bottom? It’s like the function is heading towards a certain y-value as x goes off to infinity (both positive and negative). In our graph, it looks like this horizontal asymptote is at y = 1. This tells us something about the degrees of the polynomials in the numerator and denominator.

Remember, a rational function is a fraction of polynomials. Let’s call the numerator polynomial P(x) and the denominator polynomial Q(x). So, we have f(x) = P(x) / Q(x).

There are a few rules for horizontal asymptotes based on the degrees of P(x) and Q(x):

![[FREE] Which of the following rational functions are graphed below? A](https://media.brainly.com/image/rs:fill/w:3840/q:75/plain/https://us-static.z-dn.net/files/d48/7c944c379ce4d8cbc29eff2b2213e16c.png)

- If the degree of P(x) is less than the degree of Q(x), the horizontal asymptote is y = 0 (the x-axis).

- If the degree of P(x) is equal to the degree of Q(x), the horizontal asymptote is the ratio of the leading coefficients (the coefficients of the highest power term) of P(x) and Q(x).

- If the degree of P(x) is greater than the degree of Q(x), there is no horizontal asymptote (but there might be a slant or oblique asymptote).

In our case, we have a horizontal asymptote at y = 1. This strongly suggests that the degree of the numerator is equal to the degree of the denominator. And since we’re leaning towards a denominator like x² - x - 6 (which has a degree of 2), the numerator should also have a degree of 2. That means our numerator is likely a quadratic expression of the form ax² + bx + c.

And that ratio of leading coefficients? Since the horizontal asymptote is y = 1, the leading coefficient of the numerator must be equal to the leading coefficient of the denominator. If our denominator starts with x², its leading coefficient is 1. So, our numerator must also start with 1x². This is a huge clue!

So, combining what we know, our function looks something like: f(x) = (x² + bx + c) / (x² - x - 6). Now we just need to figure out those ‘b’ and ‘c’ values, and what’s going on in the numerator. Let’s look at the graph again for more clues.

I see that the graph crosses the y-axis at a certain point. The y-intercept is where x = 0. If we plug x = 0 into our suspected function, we get: f(0) = (0² + b(0) + c) / (0² - 0 - 6) = c / -6. Looking at the graph, the y-intercept appears to be at y = -2/3. So, we have: c / -6 = -2/3. To solve for c, we can multiply both sides by -6: c = (-2/3) * (-6) = 12/3 = 4. Aha! So, our numerator now looks like x² + bx + 4.

Our function is starting to take shape: f(x) = (x² + bx + 4) / (x² - x - 6). We just need to nail down that ‘b’ value. How do we do that? We can pick a point on the graph that’s not an asymptote or an intercept and see if it fits any of our potential functions.

Let’s examine the options given to us (even though they’re not explicitly stated here, we’re assuming they’re available for us to choose from, like a multiple-choice quiz). We’re looking for a function where the numerator, when factored, doesn’t cancel out any of the factors in the denominator (x+2) or (x-3), because that would create holes, and we don’t see any obvious holes. The simplest form of the numerator we have is x² + bx + 4.

Let’s consider what the numerator might factor into. If the numerator has roots that are not -2 or 3, then we’re good. What if the numerator was something like (x + 1)(x + 4)? That would give us x² + 4x + x + 4, which is x² + 5x + 4. In this case, b would be 5. Let’s test this possibility. Our function would be f(x) = (x² + 5x + 4) / (x² - x - 6).

Let’s see if this aligns with the visual. The roots of the numerator x² + 5x + 4 = 0 are found by factoring: (x + 1)(x + 4) = 0. So, the x-intercepts would be x = -1 and x = -4. Let’s check the graph. Does it look like the graph crosses the x-axis at -1 and -4? Yes, it absolutely does! One branch clearly crosses between -0 and -2 (around -1), and the other branch crosses way over on the left side, indeed around -4.

What about the behavior of the graph in different quadrants? The left branch of the graph (for x < -2) is in the second and third quadrants, approaching the vertical asymptote at x = -2 from the left and the horizontal asymptote at y = 1 from below. The right branch of the graph (for x > 3) is in the first and fourth quadrants, approaching the vertical asymptote at x = 3 from the right and the horizontal asymptote at y = 1 from above. The middle branch (for -2 < x < 3) is in the fourth quadrant, dipping down to a minimum and then rising back up to approach the asymptotes.

Let’s consider other possibilities for the numerator, just to be sure. What if the numerator was something like x² - 4? That factors into (x - 2)(x + 2). This would mean we have a factor of (x + 2) in the numerator and the denominator. This would result in a hole at x = -2, not a vertical asymptote. So, that’s out. We need a numerator that doesn't share roots with the denominator.

What if the numerator was x² + x - 6? This factors into (x + 3)(x - 2). The roots are x = -3 and x = 2. The roots of the denominator are x = -2 and x = 3. No common roots. If this was our numerator, the function would be f(x) = (x² + x - 6) / (x² - x - 6). The horizontal asymptote would still be y = 1. The y-intercept would be -6/-6 = 1. Our graph shows a y-intercept of -2/3, so this is also incorrect.

Let’s go back to our successful candidate: f(x) = (x² + 5x + 4) / (x² - x - 6).

- Vertical asymptotes: Denominator = 0 => (x+2)(x-3) = 0 => x = -2 and x = 3. (Matches!)

- Horizontal asymptote: Degree of numerator (2) = Degree of denominator (2). Ratio of leading coefficients = 1/1 = y = 1. (Matches!)

- y-intercept: f(0) = (0² + 5(0) + 4) / (0² - 0 - 6) = 4 / -6 = -2/3. (Matches!)

- x-intercepts: Numerator = 0 => x² + 5x + 4 = 0 => (x+1)(x+4) = 0 => x = -1 and x = -4. (Matches!)

Everything seems to line up perfectly with this function. It's like all the pieces of the puzzle just clicked into place. You see, it’s not just about memorizing formulas; it’s about understanding what each part of the function does to the graph. The denominator tells you where the invisible walls (vertical asymptotes) are. The degrees and leading coefficients of the numerator and denominator tell you about the horizontal highway the graph is driving on. And the roots of the numerator tell you where the graph decides to kiss the x-axis.

Sometimes, these problems can feel a bit intimidating, like staring at a complex piece of machinery and not knowing where to start. But if you break it down, piece by piece, and look for the tell-tale signs – the asymptotes, the intercepts, the general shape – you can usually work your way to the answer. It’s like having a secret decoder ring for graphs. Pretty cool, huh?

So, if you were presented with a list of rational functions, and one of them was indeed f(x) = (x² + 5x + 4) / (x² - x - 6), you could confidently point to it and say, “That’s the one that made that picture!” It’s a great feeling when you can connect the abstract math to a visual representation. It’s no longer just numbers and letters; it’s a landscape you can explore.

Remember that nephew? He might not remember the formal definition of a rational function, but he remembers the “broken smiley face.” And now, hopefully, you’ll remember that those broken smiley faces have a distinct set of rules that govern their shape, and by looking at those rules on the graph, you can figure out the equation that created it. It's like a secret handshake between an equation and its graph. And once you learn the handshake, you can recognize anyone in the club!