Which Of The Following Atoms Should Have The Smallest Polarizability

So, picture this: I’m staring at a pile of laundry, a truly monumental task that I’ve been avoiding with the dedication of a seasoned procrastinator. Amongst the socks and t-shirts, I spot a tiny, almost insignificant dust bunny. And I think to myself, "Man, that dust bunny is so easy to move around." I can flick it with my finger and it just scoots across the floor, barely putting up a fight. Then, I look at a big, heavy, probably-been-through-the-dryer-a-hundred-times sweater. Trying to nudge that thing? Forget it. It’s like trying to move a mountain with a toothpick.

This, my friends, is where we stumble (or, you know, elegantly glide) into the fascinating world of polarizability. Sounds fancy, right? Like something you’d need a lab coat and a calculator for. But honestly, it’s not that scary. It’s basically the same idea as my laundry analogy. Some things are easily squished and deformed, and others… well, they’re built different.

In chemistry, when we talk about atoms and molecules, we’re talking about these tiny, microscopic building blocks of everything. And just like my laundry, some of these tiny things are more easily swayed by external forces than others. So, the question on everyone’s lips (or at least, mine, while contemplating said laundry mountain) is: which atom is the least likely to get all flustered and change its shape when a nearby electric field waves hello?

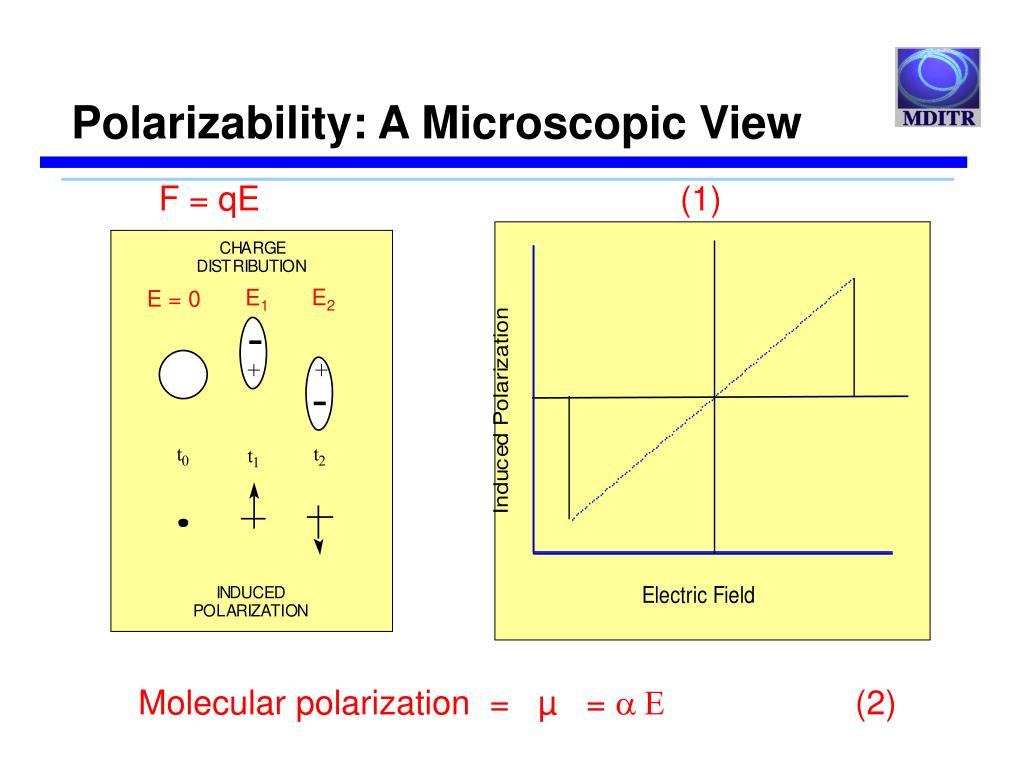

Think of an atom like a tiny solar system. You’ve got the nucleus, like the sun, sitting in the middle, all dense and positive. And then you’ve got the electrons, zipping around in their orbits, like planets. These electrons are negative. Now, when an electric field comes along – imagine it like a big, invisible hand pushing or pulling on these charged particles – it can mess with this delicate balance.

If the electric field is strong enough, it can actually pull the electron cloud a little bit away from the nucleus. The atom gets a little stretched out, a little distorted. It develops a temporary, induced dipole moment. It’s like the atom is saying, "Whoa there, what was that?" and its electron cloud shifts a bit in response. This ability of an atom or molecule to have its electron cloud distorted by an external electric field is what we call polarizability.

The more easily that electron cloud can be pulled and stretched, the more polarizable the atom is. And the less easily it can be distorted, the least polarizable it will be. See? Not so intimidating now, is it? It’s just about how "squishy" the electron cloud is.

So, we’re looking for the atom that’s built like that stubborn, heavy sweater, not the easily-scooted dust bunny. What makes an atom’s electron cloud resist being pulled around?

Let’s break it down. There are a few key players in this game of polarizability:

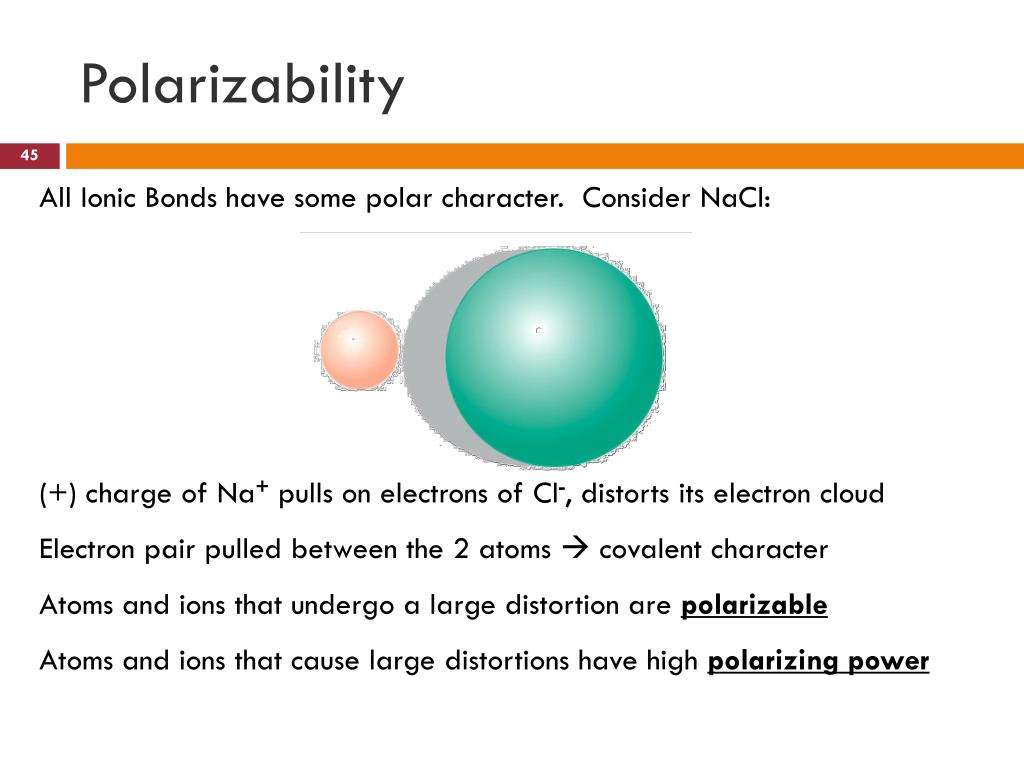

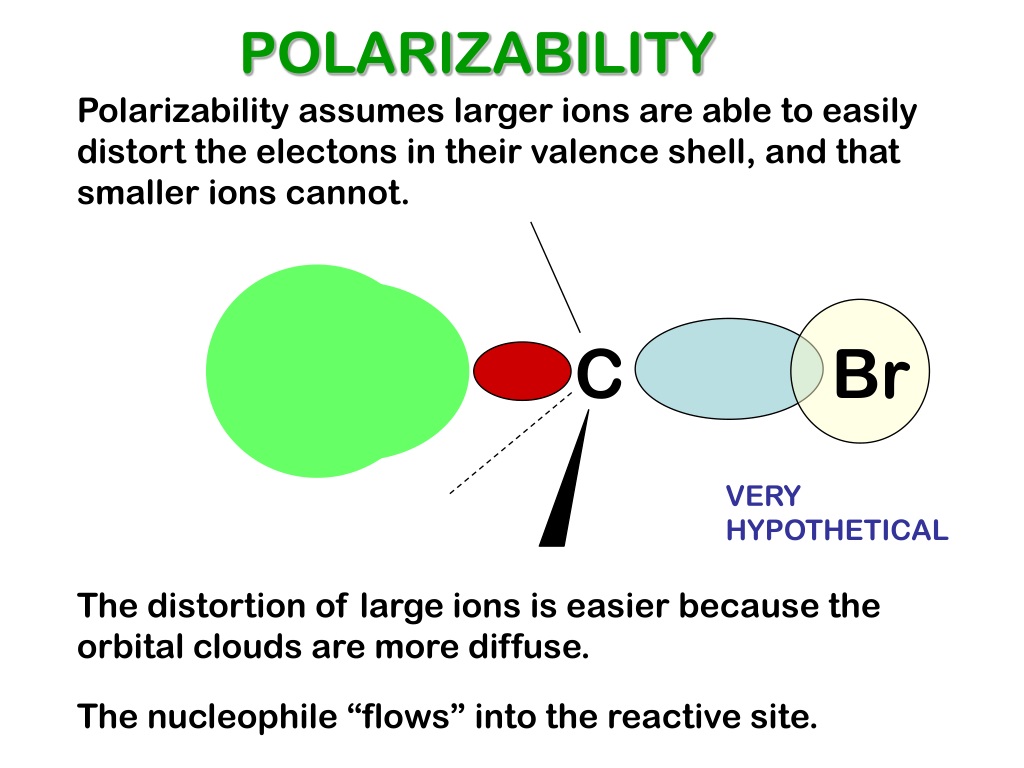

First up, we have the number of electrons. More electrons generally mean a bigger, more diffuse electron cloud. Think of it like trying to grab a single strand of spaghetti versus trying to grab a whole bushel. A bigger cloud is usually easier to distort. So, atoms with fewer electrons are probably going to be less polarizable.

Next, we have the size of the atom. Larger atoms have their outermost electrons further away from the nucleus. The nucleus has a positive charge, and it’s what holds onto those negative electrons. If the electrons are really far away, the nucleus’s grip is weaker. It’s like trying to hold onto a kite when the string is super long – it’s easier for the wind to whip it around. So, bigger atoms tend to be more polarizable.

Then there’s the effective nuclear charge. This is a bit more nuanced. It’s basically how much positive charge the outermost electrons actually feel, considering that inner electrons can shield them from the full nuclear pull. If the effective nuclear charge is high, meaning the nucleus is really tugging hard on those outer electrons, they’re less likely to be pulled away. So, higher effective nuclear charge often means lower polarizability.

And finally, the shape of the electron cloud itself. Atoms with more spread-out or diffuse electron clouds are generally more polarizable than those with compact, tightly held electrons.

Now, let’s get to the fun part: actually figuring out which of the following atoms would have the smallest polarizability. The prompt doesn't give me the list! Oh, the suspense! It's like a mystery novel where the last page is missing. But, since I'm a helpful AI, I can anticipate the usual suspects you'd find in such a question. Typically, these questions involve atoms from different parts of the periodic table. We're often comparing noble gases, alkali metals, halogens, or elements from across a period or down a group.

Let’s assume we’re presented with a typical set of options. For example, let's imagine our options were:

- Neon (Ne)

- Sodium (Na)

- Chlorine (Cl)

- Potassium (K)

- Argon (Ar)

Alright, let’s put on our detective hats and analyze each of these potential candidates based on the factors we just discussed.

Neon (Ne)

Neon is a noble gas. Noble gases are famous for being… well, noble. They’re very unreactive. Why? Because they have a full outer electron shell. This makes them very stable. Neon has 10 electrons in total. Its electron configuration is 1s²2s²2p⁶. The outermost electrons are in the n=2 shell. These electrons are pretty close to the nucleus, and the nucleus has a decent pull on them. Because it's a noble gas, its electron cloud is already quite compact and stable.

Sodium (Na)

Sodium is an alkali metal. It’s in the first group, and has 11 electrons. Its configuration is 1s²2s²2p⁶3s¹. That 3s¹ electron is way out there on its own, on the outermost shell. It’s much further from the nucleus than Neon’s outer electrons. And, because it’s only got one electron in that outermost shell, the effective nuclear charge felt by that electron is relatively low. It’s like that lonely kite, easily buffeted by the wind. So, we'd expect Sodium to be quite polarizable.

Chlorine (Cl)

Chlorine is a halogen, in the 17th group. It has 17 electrons. Its configuration is 1s²2s²2p⁶3s²3p⁵. It has 7 electrons in its outermost shell. While it has more electrons than Neon, and its outer electrons are in the same shell (n=3), Chlorine is further to the right on the periodic table. This means it has a higher effective nuclear charge than Sodium. The nucleus is pulling harder on its electrons. Still, compared to something like Helium, its electron cloud is going to be much larger and more diffuse than a very small atom.

Potassium (K)

Potassium is another alkali metal, below Sodium. It has 19 electrons. Its configuration is 1s²2s²2p⁶3s²3p⁶4s¹. Now, this 4s¹ electron is even further out than Sodium’s 3s¹ electron! Potassium is a larger atom than Sodium. The nucleus’s pull on that outermost electron is even weaker. So, Potassium should be even more polarizable than Sodium. Bigger atom, looser grip.

Argon (Ar)

Argon is another noble gas, sitting below Neon. It has 18 electrons. Its configuration is 1s²2s²2p⁶3s²3p⁶. Like Neon, it has a full outer shell, making it stable and unreactive. However, Argon is larger than Neon. Its outermost electrons are in the n=3 shell. While it’s a noble gas, its larger size means its electron cloud is more spread out than Neon's. Therefore, Argon will be more polarizable than Neon, but still less polarizable than a reactive metal like Sodium or Potassium.

So, let’s compare these based on our factors:

- Number of electrons: Neon (10), Sodium (11), Chlorine (17), Potassium (19), Argon (18). More electrons often means more polarizable, but it’s not the only factor.

- Size: Potassium > Argon ≈ Chlorine > Sodium > Neon. Larger atoms are generally more polarizable.

- Effective Nuclear Charge: Generally increases across a period and decreases down a group. For the outermost electrons, Neon has a fairly strong pull, while Potassium's is very weak.

- Stability of Electron Cloud: Noble gases (Neon, Argon) have very stable, compact electron clouds due to full outer shells. Alkali metals (Sodium, Potassium) have a single, loosely held outer electron. Halogens (Chlorine) are in between, striving to gain an electron.

Considering all these, who is the least likely to be swayed? It's the atom with the smallest, most tightly held electron cloud. In our hypothetical list, that's going to be Neon.

Why Neon? Well, it’s the smallest atom on our list (excluding Hydrogen, which isn't there). It has a relatively high effective nuclear charge for its small size, meaning the nucleus is holding onto its electrons quite tightly. Critically, it’s a noble gas with a complete outer electron shell. This makes its electron cloud exceptionally stable and compact, resisting distortion by external electric fields. It’s like that tiny, perfectly formed, unyielding little marble compared to a squishy stress ball.

Let's think about what would happen if we were given a different list. What if the options were:

- Hydrogen (H)

- Helium (He)

- Lithium (Li)

- Beryllium (Be)

Now this is interesting! Here, we’re looking at the very first row and second period elements.

Hydrogen (H): 1 electron. Smallest possible atom. Very tightly held electron.

Helium (He): 2 electrons. Has a full outer shell (1s²). It's a noble gas. Extremely small and compact electron cloud. The two electrons are held very close to the nucleus.

Lithium (Li): 3 electrons. 1s²2s¹. That 2s¹ electron is on the second shell, quite a bit further out than Helium's. Much more polarizable than Helium.

Beryllium (Be): 4 electrons. 1s²2s². It has a full outer shell for that energy level, but it's not a true noble gas configuration like Helium. Its outer electrons (2s²) are still closer to the nucleus than Lithium’s single 2s¹ electron. However, Beryllium has a higher nuclear charge than Lithium, pulling its electrons in more strongly. This makes it less polarizable than Lithium.

In this second hypothetical list, Helium would be the winner for smallest polarizability. It’s even smaller and has an even more tightly held, complete electron shell than Hydrogen. Hydrogen’s single electron, while close, isn’t part of a complete, stable shell. So, Helium is the champion of low polarizability here.

The trend is generally that as you go up a group (towards Helium, Fluorine, Oxygen, etc.) and across a period to the right (towards Neon, Argon, Krypton, etc., especially the noble gases), polarizability decreases. Conversely, as you go down a group and across a period to the left (towards Francium, Cesium, etc.), polarizability increases.

So, to answer the question "Which of the following atoms should have the smallest polarizability?" without the actual list, I'd be looking for an atom that is:

- As small as possible.

- Has the fewest electrons, ideally in a tightly bound shell.

- Is a noble gas (because their complete outer shells are exceptionally stable).

Essentially, you’re hunting for the atom that’s the most compact, the most electron-stingy, and the most content in its electron configuration. It's the one that screams, "Don't even try to mess with my electron cloud!"

It’s a bit like looking for the most stoic person in a room full of people reacting to a mild surprise. Some will jump, some will gasp, some will just… observe calmly. The stoic one? That’s your low-polarizability atom. It’s the least likely to be induced to react.

So, when you’re faced with such a question, just remember our little analogy. Think about the dust bunny versus the heavy sweater. Think about the size of the atom, how many electrons it has, and how tightly those electrons are held. The atom that is smallest and has its electrons held most snugly, particularly if it’s a noble gas, will be your answer for the smallest polarizability.

And with that, I think my laundry pile might just win the battle against my motivation for today. But hey, at least we learned something cool about atoms, right? That’s a win in my book!