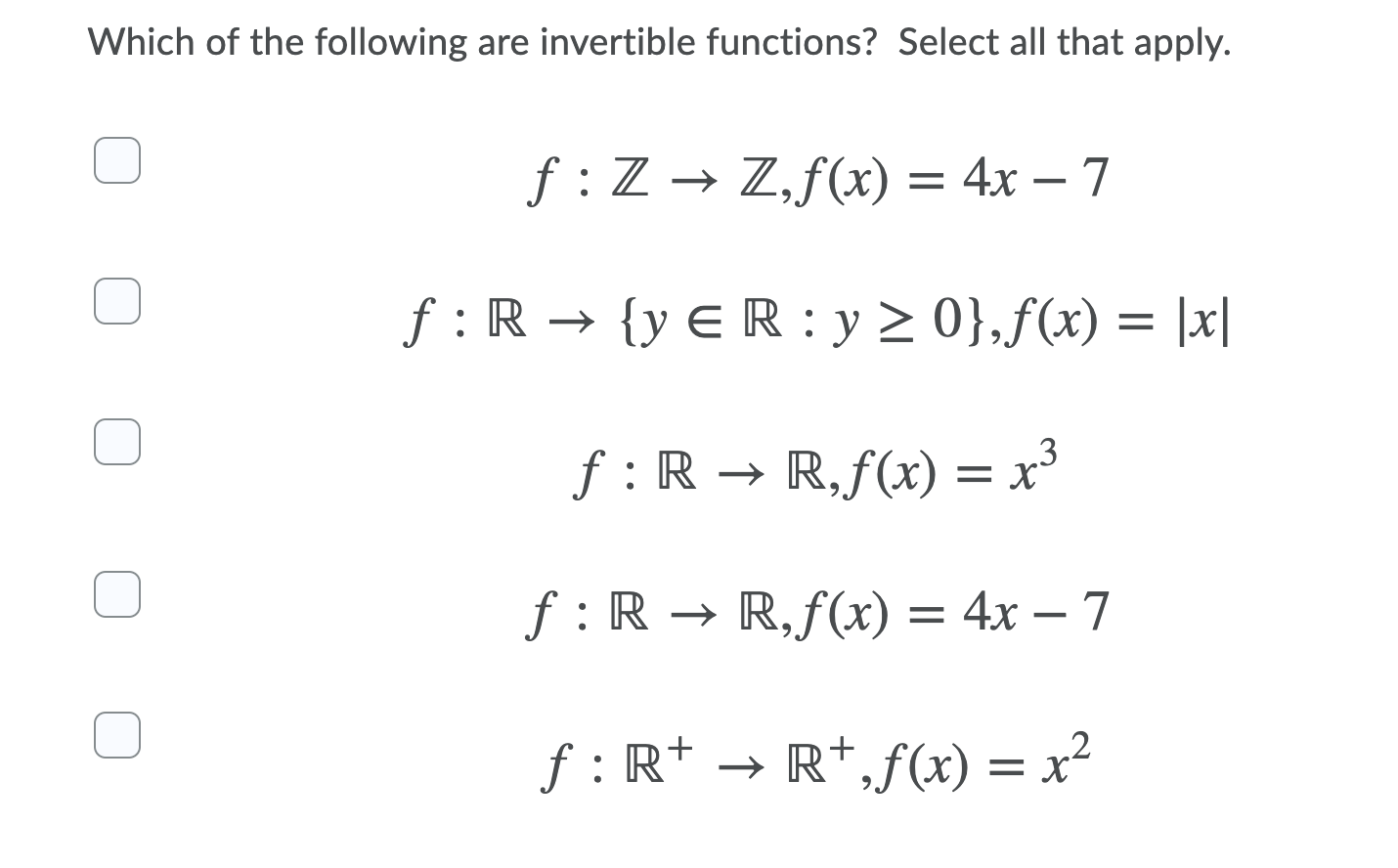

Which Functions Are Invertible Select Each Correct Answer

Hey there, coffee buddy! Let's dive into something that sounds super math-y but is actually kinda fun. We're talking about invertible functions. Sounds fancy, right? But stick with me, it’s not as scary as it looks. Think of it like trying to undo something. Did you put on a sweater? You can undo that by taking it off. Easy peasy. Functions are like that, but a little more… mathematical. Some you can totally un-do, and some? Well, they're just not built for it.

So, what's the big deal about invertibility? Basically, an invertible function is one that has a unique "undo" button. Like, if you f(x) = x + 2, you can easily figure out how to get back to x. If your result is 5, you know the original number was 3, right? Just subtract 2! See? You just invented an inverse function on the spot. High five! But what happens when a function is a bit… messy?

Imagine you have a function that takes your birthday (month and day) and tells you your astrological sign. Okay, so if I tell you I'm a Leo, can you definitely tell me my birthday? Nope! Because there are a bunch of Leo birthdays in July and August. This function, while useful for horoscope gossip, is not invertible. It’s a one-way street of information. You go from birthday to sign, but you can't go back from sign to birthday with 100% certainty. That’s a big clue, right there.

The key idea for invertibility is this: every output must have only one input. Think of it like a secret handshake. If everyone in the club has the exact same handshake, how can you tell who's who just by seeing the handshake? You can’t! It's a shared secret, not a unique identifier. A function needs to be like a secret handshake where each person has their own special move. Then, if you see the move, you know exactly who it belongs to.

This is why we need to be super careful when we're looking at graphs of functions. If a graph looks like a squiggly line that goes up and then down, or down and then up, that's a red flag, my friend. It means that at some y-value, there are actually two or more different x-values that produce that same y. This is where our handy-dandy horizontal line test comes in.

Have you heard of it? It’s so simple, you’ll wonder why you didn’t think of it yourself. You just draw a horizontal line across the graph. If that horizontal line ever crosses the graph more than once, then boom! Your function is not invertible. It’s like drawing a line through a crowd of people – if it hits more than one person, you can’t distinguish them. But if it only ever hits one person, or no one at all, then that function is a potential candidate for being invertible.

Now, let's talk about some specific types of functions you might encounter. They all have their own little personalities when it comes to invertibility. It's like a dating game for functions!

Linear Functions: The Reliable Ones

Let's start with the basics. Linear functions. You know, the ones that make nice straight lines? Like f(x) = 2x + 1 or g(x) = -x + 5. These guys are almost always your best bet for invertibility. Why? Because they're predictable. For every x, you get one unique y. And for every y, you get one unique x back.

Think about f(x) = 2x + 1. If you get an output of 7, you know for sure that the input was 3, because 2 * 3 + 1 = 7. There's no other number you could plug in to get 7. It's like a perfectly organized filing cabinet. Everything has its place, and you can always find what you're looking for.

The only time a linear function might not be invertible is if it's a completely flat line, like f(x) = 3. In this case, every single input x gives you the same output, 3. So if I tell you the output is 3, can you tell me what the input was? Nope! It could have been 1, 5, -100, anything! This is the classic case of a function that is not one-to-one, and therefore, not invertible. It’s like trying to identify someone by their shoe size when everyone in the room wears the same size.

But for any other linear function with a slope that's not zero, you’re golden. They’re your go-to for invertibility. You can always find that sweet, sweet inverse function. Just flip-flop your x and y and solve for y again. Magic!

Quadratic Functions: The Tricky Two-Timers

Ah, quadratic functions. The U-shaped beauties (or sometimes upside-down U-shaped!). Think f(x) = x^2 or g(x) = x^2 - 4. These guys are a bit more… dramatic. They’re famous for their curves. And guess what? That curve is the reason they often fail the invertibility test.

Let's take f(x) = x^2. If I plug in x = 2, I get f(2) = 4. If I plug in x = -2, I also get f(-2) = 4. Uh oh! We have two different inputs, 2 and -2, that give us the same output, 4. This is where our horizontal line test becomes your superhero cape. Draw a horizontal line at y = 4, and it will slice through the parabola of f(x) = x^2 at x = 2 and x = -2.

Because of this little quirk, the entire quadratic function f(x) = x^2 is not invertible. It’s like a celebrity who’s so famous, you can’t tell which twin you’re seeing in a picture.

However! And this is a big "however" with a sparkly exclamation mark, we can make quadratic functions invertible by restricting their domain. Remember how we talked about the domain being the set of all possible inputs? If we chop off half of the x-values, we can save the day.

For f(x) = x^2, if we only consider x ≥ 0 (the right half of the parabola), then every output y will have only one corresponding x. For example, if the output is 9, the input must be 3 (since we’re not allowing negative inputs anymore). This restricted function is invertible. Or, if we only consider x ≤ 0 (the left half), it's also invertible! It's like saying, "Okay, we'll only invite people who have birthdays in the first half of the year to this exclusive party." You've narrowed it down!

Cubic Functions: The S-Shaped Survivors

Now, cubic functions. These are the ones with the "cubed" term, like f(x) = x^3 or g(x) = x^3 - x. They often have an S-shape. And guess what? The basic cubic function, f(x) = x^3, is actually a superstar of invertibility!

Why? Because x^3 is strictly increasing (or strictly decreasing, depending on the function). For every x, there's a unique y. And for every y, there's a unique x. If you get an output of 8 from f(x) = x^3, you know the input was 2. There's no other number you can cube to get 8. This is a beautiful, clean, one-to-one relationship.

So, the simplest cubic functions, like f(x) = x^3, are indeed invertible. They pass the horizontal line test with flying colors. The horizontal line will only ever hit the S-curve once.

![[FREE] Which functions are Invertible Choose each correct answer](https://media.brainly.com/image/rs:fill/w:3840/q:75/plain/https://us-static.z-dn.net/files/dd9/757d03433b9bb9832aed9f0c77d3ed0f.png)

However, and there’s always a "however" in math, things can get a little dicey if you add other terms to the cubic function. For example, g(x) = x^3 - x. This function can actually go up, then down, then up again. It has "turning points." And if it has turning points, it can fail the horizontal line test. So, g(x) = x^3 - x is generally not invertible as a whole. It’s like a roller coaster – you can go up and down multiple times!

Exponential Functions: The Rapid Risers (or Fallers)

Exponential functions are those that have the variable in the exponent, like f(x) = 2^x or g(x) = (1/2)^x. These functions are known for their rapid growth (or decay). They either shoot upwards super fast or plummet downwards super fast.

The good news? Most basic exponential functions are invertible. Think about f(x) = 2^x. If your output is 8, your input must have been 3, because 2^3 = 8. There's no other exponent you can raise 2 to to get 8. They are always either strictly increasing or strictly decreasing. They’re like a rocket taking off – one direction, no turning back!

So, f(x) = 2^x is invertible. And g(x) = (1/2)^x (which decreases) is also invertible. They pass the horizontal line test with ease.

Logarithmic Functions: The Inverse Buddies of Exponentials

Logarithmic functions are the natural partners to exponential functions. If f(x) = b^x, then its inverse is f⁻¹(x) = log_b(x). They are, by definition, inverses of each other!

So, if your exponential function is invertible (and most basic ones are!), then its corresponding logarithmic function will also be invertible. They're like a perfectly matched pair of socks. You can’t have one without the other for a complete outfit.

Think about f(x) = log(x) (which is log base 10). If your output is 2, your input must have been 100, because log(100) = 2. It’s a clean, direct relationship. They are consistently one-to-one and thus invertible.

Trigonometric Functions: The Wavy Wonders (and Worries)

Okay, trig functions. Sine, cosine, tangent… these are the functions that describe waves and angles. And guess what? They are famously NOT invertible in their most basic, unrestricted form. Why? Because waves repeat!

Think about the sine function, sin(x). You know how sin(0) = 0, and sin(π) = 0, and sin(2π) = 0? See the problem? The output 0 happens at infinitely many different inputs (0, π, 2π, etc.). If you draw a horizontal line at y = 0 across the sine wave, it hits it over and over and over.

So, sin(x), cos(x), and tan(x) are all not invertible as they are. They are the quintessential examples of functions that fail the horizontal line test spectacularly.

BUT! Just like with quadratics, we can restrict their domains to make them invertible. This is super important in calculus and physics! When you see arcsin(x) or sin⁻¹(x) (which means the inverse sine function), mathematicians have already agreed on a specific interval to restrict the sine function to, usually from -π/2 to π/2. In that specific range, the sine function is one-to-one and therefore invertible. It's like saying, "We'll only look at the first hump of the sine wave, and ignore all the others."

Absolute Value Functions: The Mirror Makers

What about absolute value? Like f(x) = |x|? This function always gives you a positive number (or zero). Its graph looks like a V-shape.

Consider f(x) = |x|. If the output is 3, what was the input? It could have been 3, because |3| = 3. Or it could have been -3, because |-3| = 3. Once again, we have two different inputs leading to the same output.

So, f(x) = |x| fails the horizontal line test. If you draw a horizontal line at y = 3, it hits the V at x = 3 and x = -3. Therefore, the absolute value function is generally not invertible. It's like a funhouse mirror that distorts things in a way you can't always un-distort.

Rational Functions: The Fraction Frenzy

Rational functions are basically fractions where the numerator and denominator are polynomials, like f(x) = 1/x or g(x) = (x+1)/(x-2).

Let's look at f(x) = 1/x. If your output is 1/2, your input must be 2. If your output is -1, your input must be -1. This function actually is invertible. It’s a hyperbola that is nicely separated.

![[ANSWERED] which functions are invertible Select each correct answer S](https://media.kunduz.com/media/sug-question-candidate/20231106170756552300-5892375.jpg?h=512)

However, many rational functions can get messy. They can have holes, asymptotes, and curves that make them fail the horizontal line test. It really depends on the specific polynomial in the numerator and denominator. You just have to check them case by case, and the horizontal line test is your best friend here.

Piecewise Functions: The Rule-Breakers (and Rule-Makers)

Piecewise functions are a bit like a choose-your-own-adventure book. They have different "rules" (different functions) for different parts of their domain.

To check if a piecewise function is invertible, you have to check each piece and also see if the "joins" between the pieces create any problems. You might have one piece that’s invertible, and another that isn't. Or, you might have two different pieces that output the same value at their connection point.

For example, if you have a piece that is f(x) = x for x < 0 and another piece that is g(x) = x for x ≥ 0, this whole thing is not invertible because f(-2) = -2 and g(2) = 2. Wait, that example is fine. Let's try again. If you have f(x) = x for x < 0 and g(x) = 2x for x ≥ 0. If f(-1) = -1, but g(0.5) = 1. No overlap.

The key is to check if any y-value is produced by more than one x-value across the entire function. It can get complicated quickly! Always apply the horizontal line test to the entire graph of the piecewise function.

The Golden Rule: One-to-One is Key!

So, what's the ultimate takeaway from all this coffee chat? A function is invertible if and only if it is one-to-one. This means that for every unique output, there is exactly one unique input. No exceptions!

The horizontal line test is your visual superpower for spotting this. If any horizontal line cuts through your graph more than once, that function is throwing a party for multiple x-values at the same y-value, and it’s not invertible.

Remember, sometimes we can make a function invertible by being picky about its domain. We can chop off the parts that cause trouble. But if the function, as given, doesn't pass the one-to-one test, then it's not invertible on its own.

So next time you see a function, ask yourself: Can I trace back every output to a single, lonely input? If the answer is a confident "yes!", then you've found yourself an invertible function. And that, my friend, is something to celebrate with another sip of coffee!