Which Element's Atoms Have The Greatest Average Number Of Neutrons

So, picture this: I was chilling one evening, trying to impress my niece with my 'vast' scientific knowledge (which, let's be honest, mostly consists of remembering cool trivia from documentaries). I was explaining about atoms, these tiny little building blocks of everything. My niece, bless her curious little heart, asked, "Uncle, do all atoms have the same amount of stuff inside?"

It was a surprisingly good question, and it got me thinking. We talk about elements, right? Like Goldilocks and the three bears – too light, too heavy, just right. But what makes them different? Is it just the number of protons zipping around? Well, yes and no. That's what makes an element that element, but there's another little guy hanging out in the nucleus, often doing its own thing, contributing to the overall heft of the atom. I'm talking, of course, about the neutron.

And that, my friends, is how I found myself pondering the humble neutron and, ultimately, asking the question: Which element's atoms have the greatest average number of neutrons? It’s a bit of a nerdy rabbit hole, but trust me, it’s got some surprising answers.

When we learn about atoms, we usually start with the basics. You've got your protons, positively charged little dudes, and your electrons, the negatively charged wanderers. The number of protons, we're told, defines the element. Hydrogen always has one proton. Helium always has two. Uranium, famously, has 92. Simple enough, right? That's the atomic number, the element's fingerprint.

But then there are neutrons. These guys are neutral – no charge. They hang out in the nucleus right alongside the protons, like silent, weighty companions. They don't change what element an atom is, but they absolutely change its mass. Think of it like this: if protons are the personality of the atom, neutrons are the extra baggage it decides to carry around. Some atoms pack light, others go on a serious shopping spree.

This is where things get interesting. Atoms of the same element can have different numbers of neutrons. These variations are called isotopes. So, you can have, say, carbon-12 (6 protons, 6 neutrons) and carbon-14 (6 protons, 8 neutrons). Both are still carbon, but carbon-14 is heavier and, as you might know, it's the one we use for radioactive dating. Pretty neat, huh?

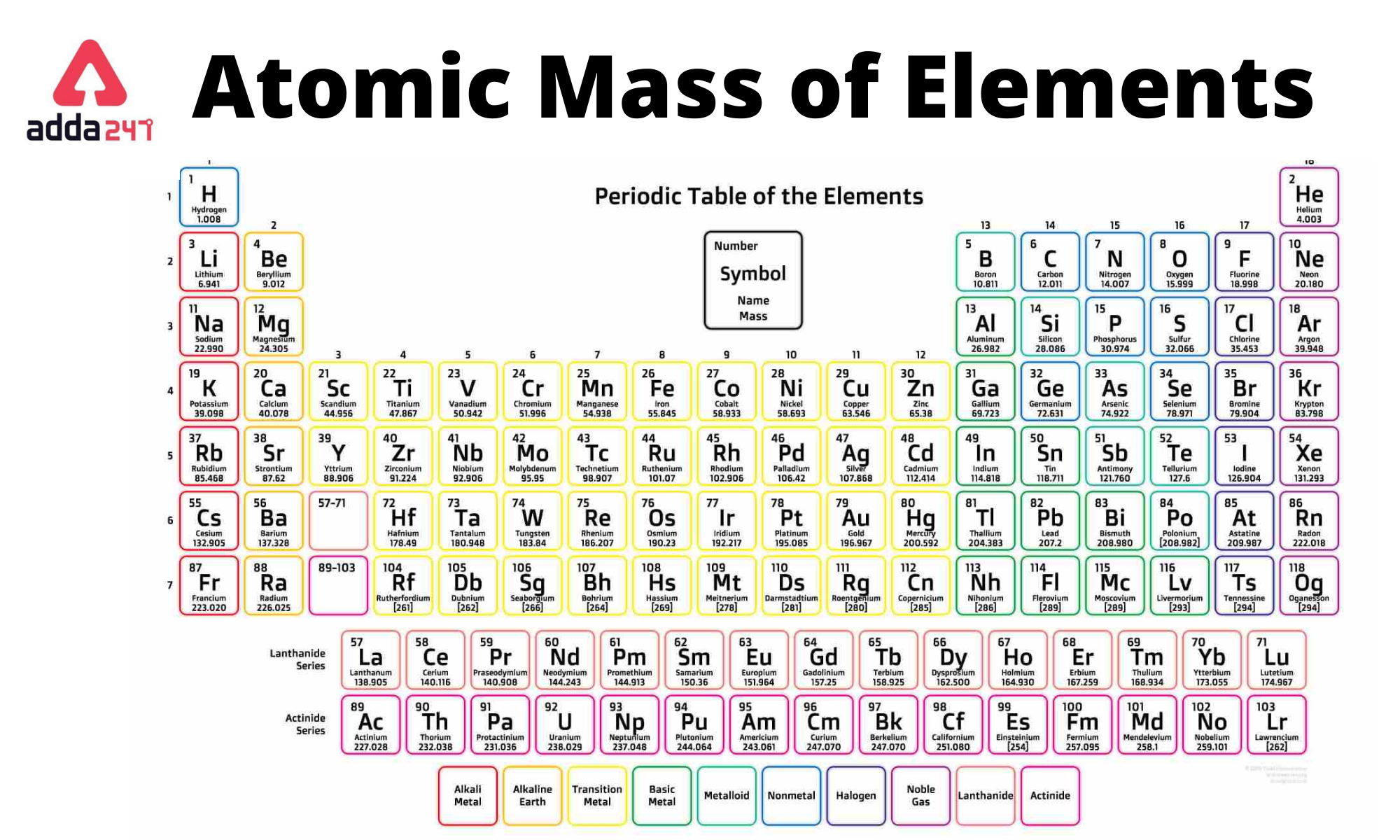

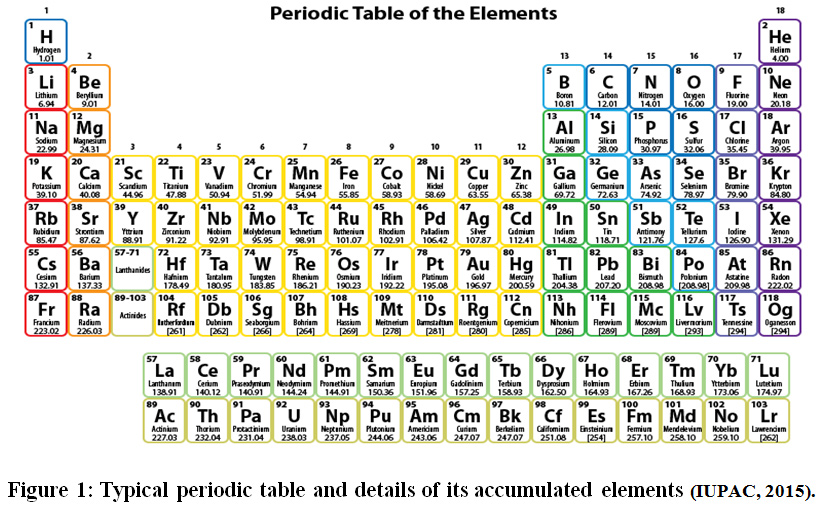

Now, if we're talking about the average number of neutrons, we're not just looking at one specific isotope. We're looking at all the naturally occurring isotopes of an element, weighted by how common they are. This is what gives us the atomic weight you see on the periodic table – that decimal number that always seems a little... imprecise. It’s that imprecision that holds the key to our neutron quest.

So, where does this lead us? We’re looking for the element where, on average, those neutron buddies are most numerous compared to the proton pals. Intuitively, you might think it’s going to be some of the really heavy elements, right? Elements at the very end of the periodic table, the ones that sound like they belong in a sci-fi movie. And you'd be on the right track, but it’s not quite as straightforward as just picking the biggest number.

Let's take a stroll down the periodic table, shall we? We start with the lightweights. Hydrogen, as we know, has no neutrons in its most common form (protium). Deuterium has one, and tritium has two. So, Hydrogen’s average is pretty low. Helium? Mostly two neutrons. Lithium? Three. We're still dealing with a fairly even split, or even more neutrons than protons as we go up.

As we move into the middle of the periodic table, things get a bit more complex. For elements like Oxygen (atomic number 8), the most common isotope, Oxygen-16, has 8 neutrons. Pretty balanced. But there are other isotopes like Oxygen-17 (9 neutrons) and Oxygen-18 (10 neutrons). So, the average might nudge slightly higher than a perfect 1:1 proton-to-neutron ratio, but not by a huge amount.

Iron (atomic number 26) is a classic example of a stable, abundant element. Its most common isotopes tend to have roughly equal numbers of protons and neutrons, or slightly more neutrons. But even here, the average is still relatively close.

Here's the thing that trips people up: the strong nuclear force. This is what holds the nucleus together, overcoming the electrical repulsion between all those positive protons. It's a delicate dance. Neutrons play a crucial role in this. They act like nuclear glue. They don't repel each other or the protons, but they do interact via the strong force. To keep a nucleus stable, especially as it gets bigger and bigger with more protons, you often need a growing number of neutrons to provide that extra binding energy and dilute the proton-proton repulsion.

This is why, for lighter elements, the number of neutrons is often equal to or slightly less than the number of protons. But as you get into the heavier elements, the neutron count starts to pull ahead. It's like the nucleus is saying, "Okay, we've got a LOT of positive charges in here. We need some neutral muscle to keep this party from blowing up!"

So, the trend is clear: the heavier the element, the more likely it is to have a higher neutron-to-proton ratio. This brings us to the very end of the periodic table, the realm of the transuranic elements. These are elements with atomic numbers greater than 92 (Uranium). Many of these are synthetic, meaning they don't occur naturally and are created in labs. They are also notoriously unstable, decaying very quickly.

But among the naturally occurring elements, we’re looking at the ones that are as close to the end as nature allows. This means we're talking about elements like lead (Pb), bismuth (Bi), and indeed, uranium (U). These guys have a lot of protons, and to keep their nuclei from flying apart, they need a substantial number of neutrons.

Let's look at some contenders. Bismuth (atomic number 83) has the isotope Bismuth-209, which has 83 protons and 126 neutrons. That's a significant surplus of neutrons! Lead (atomic number 82) has its most stable isotope, Lead-208, with 82 protons and 126 neutrons. Again, a hefty neutron count.

But what about Uranium? Uranium (atomic number 92) has a couple of main naturally occurring isotopes: Uranium-238 and Uranium-235. Uranium-238 has 92 protons and a whopping 146 neutrons. Uranium-235 has 92 protons and 143 neutrons. When you average these out, considering their natural abundance (U-238 is far more common), you get a very high average neutron number.

So, we're getting closer! We’re looking at the upper reaches of the periodic table. But there’s a subtle point: the question is about the average number of neutrons. This means we need to consider not just the heaviest isotopes, but the average across all naturally occurring isotopes.

And here's where it gets a little mind-bending. For the very heaviest elements, especially those that are barely stable enough to exist naturally in any significant quantity, their isotopes often have a very large number of neutrons relative to their protons. Think about it: the repulsive forces between protons are becoming immense. You need a lot of neutral "glue" to hold it all together.

Let's consider the element with the highest atomic number that has at least one stable isotope. That element is Lead (Pb). While Bismuth has a famously long-lived isotope (Bi-209), it's technically radioactive, albeit with a half-life longer than the age of the universe. Lead has truly stable isotopes, with Lead-208 being the most abundant and also the heaviest stable isotope of any element. Lead has 82 protons and 126 neutrons in Lead-208. This gives a neutron-to-proton ratio of 1.54. For Bismuth-209, it's 126 neutrons for 83 protons, a ratio of 1.52. Close, but Lead-208 is the king of stable neutron numbers for its proton count.

However, the question is about the average number of neutrons. This means we have to factor in all naturally occurring isotopes, even the radioactive ones. And this is where elements like Uranium and Thorium (atomic number 90) really shine. Thorium-232 has 90 protons and 142 neutrons, a ratio of 1.58. Uranium-238 has 92 protons and 146 neutrons, a ratio of 1.59. Uranium-235 has 92 protons and 143 neutrons, a ratio of 1.55.

When you calculate the average neutron numbers for these elements, taking into account their natural abundances, it gets a bit involved. But the general principle holds: the further down and to the right you go on the periodic table (towards heavier elements), the higher the neutron-to-proton ratio tends to be. This is purely a consequence of nuclear physics and the forces at play within the nucleus.

So, which element has the greatest average number of neutrons? This isn't as simple as picking the one with the highest atomic number. We need to look at elements that have isotopes with a significant number of neutrons, and then consider their natural abundance. Elements like Plutonium (Pu) and Americium (Am), while primarily synthetic, have isotopes with very high neutron counts. But the question implies naturally occurring elements.

Among the naturally occurring elements, elements at the very end of the stable and near-stable part of the periodic table are the prime candidates. We're talking about elements like Uranium (U). Uranium-238, with its 146 neutrons for 92 protons, is the most abundant isotope of Uranium and contributes significantly to its average neutron count. When you factor in the slightly less abundant Uranium-235 (143 neutrons), the average number of neutrons per Uranium atom is quite high.

Let's get a bit more specific with numbers, because, you know, nerdy fun! For Uranium (atomic number 92), the naturally occurring isotopes are predominantly U-238 (99.274% abundance) and U-235 (0.720% abundance). U-238 has 92 protons and 146 neutrons. U-235 has 92 protons and 143 neutrons. The average number of neutrons is approximately: (0.99274 * 146) + (0.720 * 143) = 144.94 + 102.96 = 247.9. That's the total number of nucleons. To get the average number of neutrons, we subtract the protons: 247.9 - 92 = 155.9. Wait, that's not right. My quick calculation was for total nucleons. Let's re-calculate the average neutrons:

Average neutrons = (0.99274 * 146) + (0.720 * 143) = 144.94 + 102.96 = 247.9. This is the average mass number. The average number of neutrons is the average mass number minus the atomic number: 237.026 (average atomic mass) - 92 (protons) = 145.026 neutrons on average for Uranium.

Let's compare this to Thorium (atomic number 90). The most common isotope is Thorium-232, which is essentially 100% abundant in nature. Thorium-232 has 90 protons and 142 neutrons. So, the average number of neutrons for Thorium is 142.

What about Lead? The most abundant isotope is Lead-208 (52.4%). It has 82 protons and 126 neutrons. Lead-207 (22.1%) has 82 protons and 125 neutrons. Lead-206 (24.1%) has 82 protons and 124 neutrons. Lead-204 (1.4%) has 82 protons and 122 neutrons. Average neutrons for Lead: (0.524 * 126) + (0.221 * 125) + (0.241 * 124) + (0.014 * 122) = 66.024 + 27.625 + 29.884 + 1.708 = 125.241 neutrons on average for Lead.

Okay, so it's looking like Uranium is a strong contender, with an average of around 145 neutrons. What about elements beyond Uranium that are still found in trace amounts naturally, like Plutonium? Plutonium-244 is found in extremely minute quantities in nature. It has 94 protons and 150 neutrons. If we were to consider such trace elements, they would push the average even higher.

However, when we usually talk about naturally occurring elements, we're referring to those present in detectable quantities. In that context, Uranium, with its high abundance of U-238 (which has a very high neutron count) and its position at the end of the natural periodic table, emerges as the likely winner for the greatest average number of neutrons.

It’s a fascinating interplay of nuclear stability and the sheer brute force required to keep a nucleus of so many protons together. Those neutrons are the unsung heroes of the heavy elements, providing the necessary bulk and binding energy. So, the next time you see Uranium on the periodic table, remember it’s not just about the 92 protons; it’s also about the significant entourage of neutrons that allow it to exist at all.

And there you have it! A little bit of atomic physics trivia to spice up your day. Who knew that the humble neutron could lead us on such an epic journey across the periodic table? It's a good reminder that even the smallest things can have the biggest impact, and that sometimes, the most interesting answers are found in the most unexpected places. Now, if you'll excuse me, I think I need to go find a more impressive science fact for my niece. Perhaps something involving black holes?