What Part Of The Pig Is Gammon: Complete Guide & Key Details

I remember the first time I encountered gammon. It was at a rather posh Christmas dinner, the kind where the crackers have ridiculously tiny puzzles inside and everyone wears their most festive, slightly-too-tight jumper. My plate arrived, piled high with all the usual suspects – roast potatoes, Brussels sprouts (yes, I’m one of those people who actually enjoys them), and then… this glistening, slightly pink, cured pork. It looked like a fancy ham, but the waiter called it gammon. I blinked. "Is it... related to ham?" I asked, feeling a bit like I was asking if a poodle was related to a wolf.

The waiter, bless his heart, gave me a look that said, "Oh, you sweet summer child," and launched into a brief explanation. But honestly, my brain was already halfway to the dessert table. It wasn't until later, rummaging through cookbooks and, let’s be honest, a few late-night internet rabbit holes, that I truly started to unravel the mystery of gammon. And let me tell you, it’s a bit more fascinating than just "fancy ham."

So, What Exactly is Gammon? Let's Get Down to Brass Tacks (or Pork Cuts, if you will!)

Alright, so gammon isn't just a fancy word for ham. That’s the first crucial bit of information I want to lodge in your brain. Think of it like this: ham is a broad category, and gammon is a very specific, often delicious, member of that family. In essence, gammon is the hind leg of a pig that has been cured. Simple, right? Well, as with most things involving delicious cured meats, there's a little more nuance.

The key here is the curing process. This is what transforms a raw pork leg into the glorious, slightly salty, often subtly sweet gammon we know and love. This curing typically involves a combination of salt, and often other preservatives like nitrates and nitrites, and sometimes sugar. The process can be done in a few ways: dry-curing (rubbing the meat with a salt mixture) or wet-curing (immersing it in a brine solution).

Now, you might be thinking, "Wait a minute, isn't that what they do to ham too?" And you’d be almost right! The distinction, often a subtle one and sometimes debated fiercely by purists (you know the type, the ones who will lecture you on the proper way to butter toast), lies in the cut of meat and, crucially, the weight.

The Cut: It's All About the Leg, Baby!

So, here's where we get specific. Gammon comes from the hind leg of the pig. This is the same primal cut that produces ham. But there's a bit of a dividing line. In the UK, where gammon is particularly popular, a cut from the hind leg that weighs over 5.5 kg (around 12 lbs) is generally classified as a ham. Anything below that weight, but still from the hind leg and cured, is typically considered gammon.

Why the weight distinction? Honestly, it's a bit of a historical and commercial thing. It helps to differentiate between the larger, whole hams often sold for roasting and the smaller, more manageable cuts that are perfect for frying or grilling. Think of it as a culinary categorisation, a way to help butchers and consumers alike understand what they're buying and how best to cook it.

So, if you buy a cured hind leg of pork from the butcher and it’s under that 5.5kg mark, chances are you’ve got yourself some gammon. If it’s a behemoth, it’s probably a ham. But don't stress too much about it; the core principle remains: it’s a cured hind leg of pork.

The Curing Process: The Secret Sauce (or Salt!)

As I touched on, the curing is what elevates a simple pork leg into gammon. This isn't just about adding flavour; it's also about preservation. Historically, curing was a vital method of keeping meat edible for longer periods, especially before modern refrigeration. Salt draws out moisture, making it harder for bacteria to thrive, and nitrates/nitrites (which also contribute to that lovely pink colour and distinct flavour) further inhibit bacterial growth.

There are two main methods:

- Dry Curing: This is where the salt and curing agents are rubbed directly onto the surface of the pork leg. It’s a slower process, allowing the flavours to penetrate deeply. Think of the traditional, air-dried hams you see hanging in Spanish delis – that’s the spirit of dry-curing.

- Wet Curing (Brining): This involves submerging the pork leg in a salty liquid, often with added sugars, spices, and flavourings. This method is generally quicker and results in a more evenly distributed flavour and moisture throughout the meat. This is probably the most common method for supermarket gammon.

The choice of curing method can affect the final texture and flavour of the gammon. Dry-cured gammon might be firmer and more intensely flavoured, while wet-cured gammon tends to be juicier and milder. Both are delicious in their own right, of course!

Gammon Steaks vs. Gammon Joints: Let's Not Get Confused!

This is another area where people sometimes get a little muddled. You’ll often see "gammon steaks" in the supermarket. These are, as the name suggests, slices cut from a larger gammon joint. They’re incredibly convenient for quick meals, usually fried or grilled and served with an egg (the classic combo, right?).

A gammon joint, on the other hand, is the whole, cured hind leg (or a substantial portion of it) that you might roast. So, while both are gammon, one is pre-portioned for speed, and the other is for a more traditional roast dinner experience.

It’s important to note that sometimes, "ham" is used interchangeably for these cured pork products, especially in different regions or countries. But in the UK context, the distinction, however fuzzy, is there. And hey, we’re here to explore the nuances!

What Makes Gammon Different from Ham? A Deeper Dive

Okay, so we know the weight and cut are key differentiators, but what about the flavour and texture? Generally speaking, gammon tends to be saltier and more intensely flavoured than a typical cooked ham. This is due to the curing process being more pronounced for the cuts that fall into the gammon category. It's designed to be quite robust.

Ham, especially a larger roasted ham, is often a bit milder and can be sweeter, sometimes glazed with honey or mustard. Gammon, while it can be glazed, often shines with its inherent cured flavour. Think of it as gammon being the bold, punchy cousin, and ham being the more refined, subtly elegant one.

Texture-wise, gammon can be a little firmer than some hams, especially if it’s been dry-cured. But it’s still wonderfully tender and succulent when cooked correctly. And let’s not forget the delicious fat cap that often accompanies a gammon joint – it renders down beautifully, adding incredible flavour and moisture to the meat.

So, to reiterate, while they are closely related (both being cured pig hind legs), the distinction usually boils down to:

- Weight: Below 5.5kg = Gammon (UK definition)

- Curing Intensity: Gammon often has a more pronounced cured flavour.

- Typical Use: Gammon steaks for frying/grilling, gammon joints for roasting.

Is this distinction always rigidly followed? Probably not. There's a lot of overlap, and marketing can be… creative. But understanding the general principles gives you a good handle on what you're purchasing.

The Wonderful World of Cooking Gammon

Now for the fun part! How do you cook this delightful cured pork? Well, you’re in luck, because gammon is remarkably versatile and forgiving. The curing means it’s already partly cooked, which makes your life a lot easier.

For Gammon Steaks: These are your go-to for a quick meal. You can fry them in a little oil or butter until they're cooked through and nicely browned. The classic pairing is, of course, with a fried egg (or two!). Some people like to score the fat cap before frying to help it crisp up. Delicious! Other options include serving with pineapple rings (a retro classic, but surprisingly good!), or in a sandwich.

For Gammon Joints: These are perfect for a Sunday roast or a special occasion. You have a few cooking methods:

- Roasting: This is the most traditional method. You can roast it in the oven, often with a little water or cider in the bottom of the roasting tin to keep it moist. Once cooked, you can remove the rind (if it has one), score the fat, and glaze it with something delicious like brown sugar, mustard, honey, or even a mixture of marmalade. Then, pop it back in the oven to caramelise that glaze. Pure magic.

- Boiling: Some people prefer to boil their gammon joint first to tenderise it before roasting or grilling. This can result in a very tender and moist finished product.

- Slow Cooker: If you're feeling lazy (no judgment here, I've been there!), a slow cooker is a fantastic way to cook a gammon joint. Just pop it in with some liquid (cider, water, or even cola – yes, cola!) and let it do its thing for several hours.

The key to cooking gammon is not to overdo it. Because it’s cured, you’re essentially just cooking it through and tenderising it, and maybe caramelising any glaze. Overcooking will result in a dry, tough piece of pork, and nobody wants that.

Serving Suggestions: Beyond the Egg

While the fried egg and gammon combination is iconic, there are so many other ways to enjoy this flavourful meat. Think about:

- Gammon Steaks: In a hearty pub-style meal with chips and peas. As part of a ploughman’s lunch. In a crusty bread roll with apple sauce.

- Gammon Joints: Sliced and served cold on a buffet table. As part of a big family roast with all the trimmings. Cubed and added to stews or casseroles.

The salty, savoury flavour of gammon pairs wonderfully with sweet elements, like apple sauce, pineapple, or glazes. It also stands up well to robust flavours, so don't be afraid to experiment with mustards, spices, and herbs.

Gammon vs. Bacon: Are We Talking About the Same Animal?

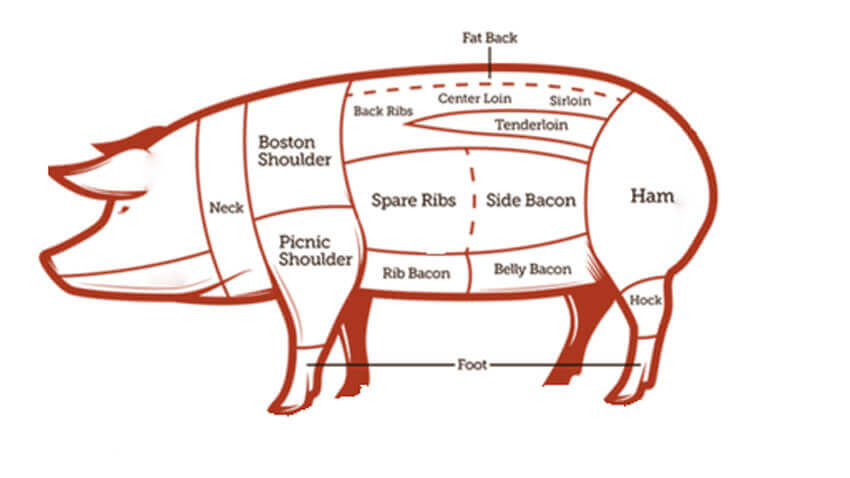

This is a question I get asked a lot, and it’s a good one! While both gammon and bacon come from pigs, they are distinctly different. Bacon is typically made from the belly of the pig, which is a much fattier cut. It’s usually cured and then smoked, which gives it that characteristic smoky flavour.

Gammon, as we've established, is from the hind leg. It has less fat overall than bacon (though it does have a lovely fat cap!) and is generally less intensely smoky, if smoked at all. The texture is also different – bacon is often crispier when cooked, while gammon can be more tender and succulent.

So, while they’re both delicious pork products, they come from different parts of the pig and are prepared differently, leading to distinct flavours and textures. You wouldn’t want to substitute gammon for bacon in a recipe that relies on the crispiness and smoky notes of bacon, and vice versa.

The Verdict: Gammon is Pretty Darn Special

So there you have it. Gammon, that slightly enigmatic, delicious cured hind leg of pork. It’s a staple in many British kitchens for good reason. It’s versatile, flavourful, and relatively easy to cook. Whether you’re a fan of the quick and easy gammon steak or the more involved gammon joint roast, there’s a way to enjoy it that suits your needs.

The next time you’re staring at a piece of cured pork in the supermarket, take a moment. Is it a big, impressive cut from the hind leg? Does it have that slightly pink hue and enticing aroma? Chances are, you’re looking at gammon. And now you know exactly what part of the pig it is and what makes it so darn tasty. So go forth, cook it, eat it, and enjoy the gloriousness that is gammon!