The Unpaired Nucleotides Produced By The Action Of Restriction Enzymes

Hey there, science curious friend! Ever heard of those fancy little molecular scissors called restriction enzymes? They're like the ultimate bouncers at the DNA club, only letting in the "right" sequences. And when they do their job, sometimes, they leave behind a little something… a little something that’s kind of like a tiny, dangling party favor. We’re talking about unpaired nucleotides, and trust me, they’re more interesting than they sound!

So, imagine DNA as a super-long, perfectly paired ladder. You’ve got your A’s always with T’s, and your C’s always with G’s, right? It's like a perfectly balanced relationship. But restriction enzymes? They're not always about perfect symmetry. Sometimes, they're more like the friend who accidentally rips a page out of a book, leaving a little bit sticking out. It’s not a mistake, per se, just a consequence of their… enthusiastic cutting.

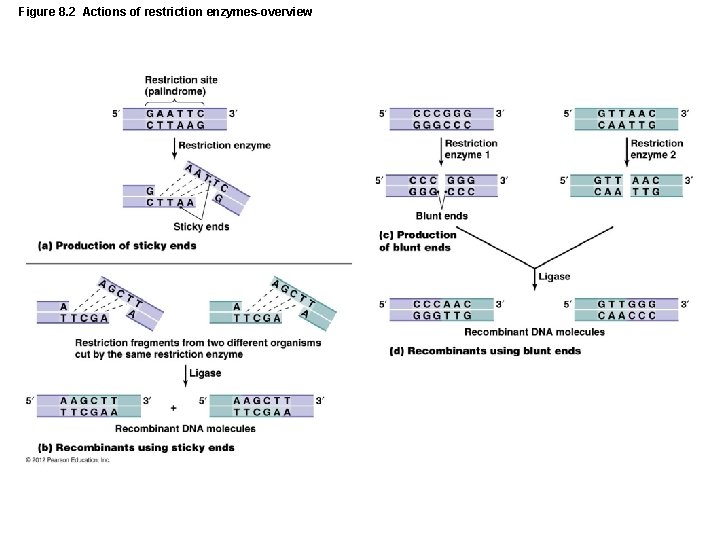

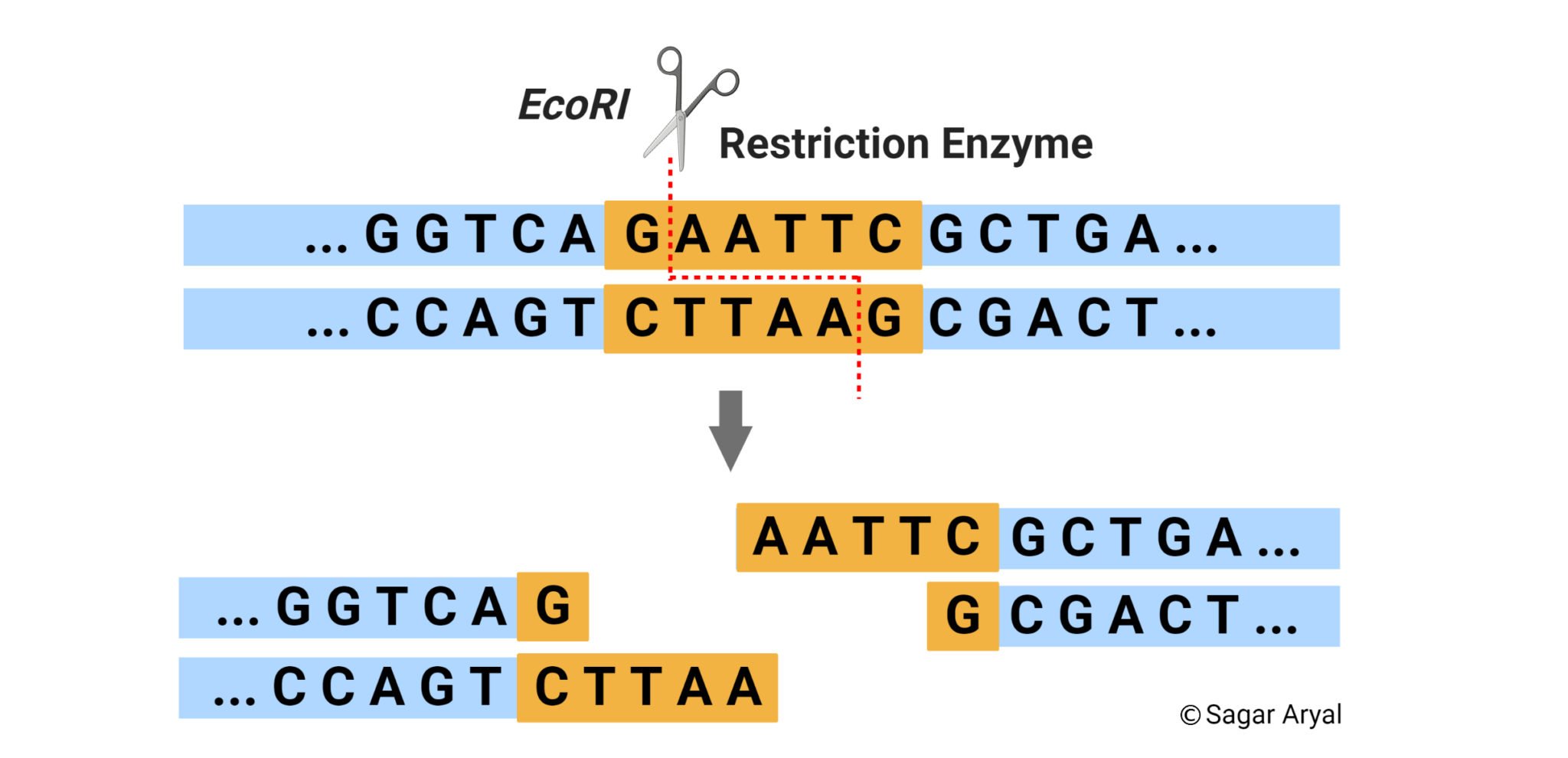

These enzymes are super specific. They recognize a particular sequence of DNA, like a secret handshake. Let's say our restriction enzyme, let's call him "Rick," only cuts when he sees the sequence "GATC". Now, DNA isn't just floating around willy-nilly. It's double-stranded. So, Rick sees "GATC" on one strand, and directly opposite it, he sees "CTAG" (because C always pairs with G, and T with A).

Here's where the fun begins! Rick doesn't cut straight across the ladder like a neat little guillotine. Oh no. Rick is a bit more… artistic. He'll often make his cuts in a staggered fashion. Imagine Rick cutting between the G and the A on one strand, and then a little further down, between the T and the C on the other strand. It's like he’s giving the DNA a little shimmy before he splits it.

What does this staggered cut produce? You guessed it! After Rick makes his snip-snip, you end up with two pieces of DNA. And each of those pieces now has a little bit of single-stranded DNA sticking out, like a single, lonely sock that lost its mate. These are our unpaired nucleotides. They’re also sometimes called "sticky ends" because, well, they’re a bit sticky and love to pair up with something complementary!

Think about it: one piece of DNA now ends with, say, a single adenine (A) hanging off. The other piece ends with a single thymine (T) hanging off, right where the cut happened. They’re now exposed and ready to mingle. It’s a bit like after a concert, where everyone’s mingling outside, looking for someone to talk to.

These sticky ends are the magic behind a lot of cool molecular biology techniques. Why? Because they're designed to find their perfect match. If you have a DNA strand ending with an "A" overhang, it will preferentially pair up with another DNA strand that has a "T" overhang right there. It's like a biological dating app, where the enzymes have already done the initial matching work!

The "Sticky" Business

So, Rick, our enzyme friend, has these sticky ends. Why are they called "sticky"? It's because they have this tendency to anneal, or stick, to other DNA fragments that have complementary sticky ends. This is incredibly useful in the lab. Imagine you want to insert a specific gene into a piece of DNA. You can use a restriction enzyme that cuts both your gene of interest and your DNA "backbone" in a way that creates complementary sticky ends.

Once they have those complementary sticky ends, the two pieces of DNA are drawn to each other. It’s a bit like magnets, but with bases! The A on one end is attracted to the T on the other, and the C to the G. This initial pairing is driven by hydrogen bonds, the same kind of weak bonds that hold the entire DNA double helix together.

After this initial sticky-end pairing, there's still a tiny gap in the sugar-phosphate backbone. This is where another enzyme, called DNA ligase (think of it as the superglue of the molecular world), comes in. Ligase fills in that gap, permanently joining the two DNA fragments together. Voila! You've just successfully inserted your gene. It’s like building with LEGOs, but way more precise and with DNA.

It's important to remember that not all restriction enzymes produce sticky ends. Some cut straight across, creating what are called "blunt ends." Blunt ends are just as the name suggests – flat and even. They don't have any overhangs. These are like perfectly square LEGO bricks that can connect to anything, but they don't have that specific, complementary attraction like sticky ends do. While blunt-end ligation is possible, it's generally less efficient than sticky-end ligation.

Why Do Nature's Scissors Do This?

You might be wondering, "Why would these enzymes even create these unpaired bits in the first place? Isn't it messy?" Well, it turns out this is actually a pretty clever evolutionary trick! Restriction enzymes are part of a bacterial defense system called the CRISPR-Cas system (though that’s a whole other exciting topic!).

Bacteria use restriction enzymes to chop up foreign DNA, like that from invading viruses. The enzyme recognizes the viral DNA sequence and slices it up, rendering it harmless. The bacterium’s own DNA is protected because it has specific chemical tags (usually methylation) that prevent the restriction enzyme from cutting it. It's like the bacteria having their own "do not cut" list for their own DNA.

The sticky ends produced by restriction enzymes actually make it easier for the cell to degrade the foreign DNA. Once the viral DNA is cut into smaller pieces with these sticky ends, other enzymes can more efficiently break down those fragments. So, while they look like little accidents to us, these unpaired nucleotides are actually part of a sophisticated defense mechanism!

It's also worth noting that the recognition site – the specific DNA sequence that the restriction enzyme binds to and cuts – is usually a palindrome. This means the sequence reads the same forwards and backward on opposite strands. For example, "GAATTC" on one strand is "CTTAAG" on the complementary strand. When you read it from left to right on the top strand and right to left on the bottom strand, it's the same sequence. This symmetry is what allows for those beautifully staggered cuts that create the sticky ends. It’s like a perfectly symmetrical design, leading to perfectly (or imperfectly, in a good way!) symmetrical cuts.

The Power of the Overhang

So, these little unpaired nucleotides, these "sticky ends," are the unsung heroes of so many molecular biology techniques. They're the key to gene cloning, where scientists insert genes into plasmids (small, circular pieces of DNA) to study them or produce proteins. They’re crucial in DNA fingerprinting, where variations in restriction enzyme cutting patterns can identify individuals.

Think about it. Without these sticky ends, creating recombinant DNA – DNA made from different sources – would be a much clunkier process. It’s like trying to build a complex structure with only blunt-ended pieces; it’s possible, but it lacks the precision and efficiency that sticky ends provide.

The beauty is in their simplicity and their specificity. A particular restriction enzyme will always cut at the same recognition site, producing the same sticky ends. This predictability is what makes them such reliable tools for scientists. It’s like having a set of precise tools in a toolbox; you know exactly what each one will do.

And the best part? These unpaired nucleotides are not a sign of a flawed system. They are a testament to the elegance and ingenuity of biological processes. They are the result of a system that evolved to defend and adapt, and in doing so, gifted us with the ability to manipulate and understand the very building blocks of life.

So, the next time you hear about restriction enzymes, remember those little sticky ends. They might seem small and insignificant, just a few unpaired nucleotides, but they are the tiny, dangling threads that connect different pieces of DNA, paving the way for scientific discovery and innovation. They are the whispers of possibility, the invitation to create, and a beautiful reminder that sometimes, the most exciting things come from a little bit of an overhang!

And as you ponder these amazing molecular tools, I hope you’re left with a sense of wonder. The world of DNA is full of these incredible, intricate mechanisms, and even the seemingly small details, like those unpaired nucleotides, play a starring role. So, keep exploring, keep questioning, and remember that even a tiny bit of unpaired DNA can lead to something truly grand. Happy imagining!