The Truth About As More Americans Disapprove, I'm Sure History Wil: Everything We Know

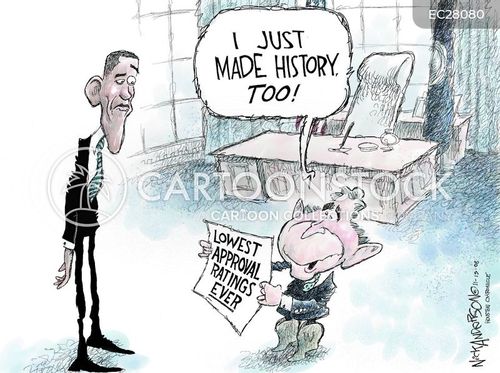

I was recently scrolling through a very online forum, you know the kind – where opinions fly faster than you can say "unverified source." Someone had posted a poll, a rather stark one, showing a significant uptick in disapproval for… well, let's just say a prominent figure or policy. The comments section immediately exploded. It was a digital tornado of takes, analyses, and predictions. And then, amidst the chaos, a phrase popped up that really snagged my attention: "As more Americans disapprove, I'm sure history will..."

And that's it. The ellipsis. The pregnant pause. It’s like a dangling participle of destiny. What will history do? Will it vindicate the disapprovers? Will it shrug them off as a fleeting moment? Will it rewrite the entire narrative? It got me thinking, really thinking, about how we, as humans, try to know history, to predict it, to shape it, even, and how often our current perceptions are a wobbly, precarious foundation for what future generations might actually deem important.

Because let's be honest, right now, we're swimming in a sea of information. Every single day, we're bombarded with news, opinions, hot takes, and analyses. It's like trying to drink from a firehose, and a lot of it is, let's face it, designed to make you feel a certain way. Especially when it comes to politics and public figures. We all have our camps, our narratives, our heroes and villains of the moment. And when a poll shows disapproval rising, it feels like a sign. A prophecy, almost. We sure history will remember this, right?

But here's the kicker, the thing that tickles my ironic bone: the further away we get from any given moment, the more that moment tends to condense, to simplify, and often, to get completely reinterpreted. What seems monumentally important, world-altering even, to us now, might be a footnote, a curious anomaly, or even a punchline to someone in, say, 2073. Ever looked back at old newspapers from 50 or 100 years ago? The front-page news of yesterday is often relegated to the back pages, or just plain forgotten, in the grand sweep of time.

Think about it. We're living through what feels like the most crucial period. Every election, every controversy, every economic shift feels like it's on the brink of changing everything. And yes, sometimes it does. But history, my friends, has a way of surprising us with its indifference to our immediate anxieties.

We tend to project our current values and understandings onto the past. We want to believe that the "right" side of history will eventually prevail. And often, it does, in some form. But the definition of "right" can shift dramatically. What was once a heroic achievement might later be seen as a grave injustice. And what was once condemned could, with enough time and a change in perspective, be re-evaluated as a necessary, albeit imperfect, step.

So, when we see that disapproval meter ticking up, and we smugly think, "History will remember this!" – who exactly is "history"? Is it an impartial judge with a perfect memory and an objective scorecard? Or is it a collective storytelling project, constantly revised and reinterpreted by the people living through it, and then by the people who come after?

Let’s dive a bit deeper into this. We're all historians in our own way, aren't we? We construct our personal histories, our family histories, and we participate in the collective historical narrative through our conversations, our social media, and our voting. And in the heat of the moment, we often want history to validate our current feelings. If we disapprove of something, we want history to tell us we were right to disapprove. It's a comforting thought, a way to feel that our present actions have lasting significance.

But the reality is far more messy. Historical consensus is a slippery thing. Consider figures who were once celebrated and later vilified, or vice versa. Think about how our understanding of slavery, colonialism, or even technological advancement has evolved. What was once seen as progress can later be revealed as exploitation. What was once considered a fringe idea can become mainstream. It’s rarely a straight line, is it?

And this is where the irony truly bites. We assume that more disapproval automatically means history will side with the disapprovers. It's a logical leap, perhaps, but not necessarily a sound one. The reasons for disapproval matter. The context matters. And the narratives that emerge decades or centuries later matter even more. History isn't just a tally of opinions; it's a story told through documents, artifacts, and, crucially, through the lens of subsequent generations.

Think about the Roman Empire. We have countless historical accounts, archaeological finds, and centuries of scholarly debate. But our understanding of Roman society, its triumphs and its failings, is constantly being refined. What was once seen as the zenith of civilization could, through a different lens, be viewed as a brutal, exploitative empire. The "truth" about Rome isn't a fixed entity; it's a continuous conversation.

And we're having that conversation right now, about our own time. The rising tide of disapproval for… well, for whatever it is that's currently drawing ire… feels significant. And it is significant, for us, now. It shapes our present, it influences our decisions, and it creates the raw material that future historians will sift through.

But here’s a thought that might make your head spin a little: What if the things we're disapproving of now are, in the long run, completely overshadowed by something else entirely? What if a technological leap, a natural disaster, or a geopolitical shift that we can’t even fathom right now completely rewrites the script, rendering our current debates quaintly irrelevant?

It's a humbling thought, isn't it? To realize that our most passionate pronouncements, our most deeply held convictions, might be viewed through a vastly different prism by those who come after us. We are, in a sense, the temporary custodians of history, shaping it with our actions and our opinions, but ultimately, it’s history that gets to decide what it keeps, what it discards, and what it reinterprets.

Consider the sheer volume of information we’re generating. Social media alone produces an unfathomable amount of data every single second. Future historians will have a treasure trove, but also a bewildering, perhaps even paralyzing, amount of noise to sift through. How will they distinguish between a fleeting meme and a genuine social movement? Between a manufactured outrage and a deeply felt grievance?

This is where the "truth" about what we know, or think we know, about history becomes so fascinating. We operate under the assumption that there's an objective truth, a definitive account waiting to be unearthed. And to some extent, there is. Facts exist. Events happened. But the meaning we ascribe to those events, the lessons we draw, and the narratives we construct are inherently subjective and fluid.

So, when more Americans disapprove, what will history do? It will probably do what it always does: it will tell a story. A story pieced together from the fragmented evidence we leave behind. It will be influenced by the prevailing ideologies of its time. It will be shaped by the questions it’s asking. And it will, most likely, surprise us with its conclusions.

Perhaps history will see our current disapproval as a crucial turning point, a moment where collective conscience finally asserted itself. Or, perhaps it will see it as a tempest in a teapot, a fascinating but ultimately minor ripple in a much larger ocean of change. Or, and this is the really intriguing possibility, it might view the entire spectacle through an entirely unexpected lens, one that we, with our immediate concerns and limited perspectives, can’t even begin to imagine.

It’s why engaging with history, real history, is so important. Not just the sanitized, simplified versions we often get, but the messy, contradictory, and evolving accounts. It teaches us humility. It teaches us that our current moment is not necessarily the absolute apex or nadir of human experience. And it reminds us that the grand narrative is still being written, and we, with our disprovals and approvals, are just one chapter.

So, next time you see a poll, and you feel that urge to exclaim, "History will remember this!" – pause for a moment. Consider the sheer, magnificent, and sometimes infuriatingly elusive nature of the historical record. We’re all participants, but history, in the end, is the ultimate editor. And its editorial decisions are rarely made in real-time, or with the benefit of our immediate, passionately held opinions.

The truth is, we think we know. We analyze, we predict, we strategize based on what we believe history will record. But what we truly know is that history is a story we’re still co-authoring, and the final draft is a long, long way from being complete. And honestly, that's kind of exciting, isn't it? It leaves room for surprises.