The Transmembrane Domain Of An Integral Membrane Protein

You know, I was just staring at a picture of a cell the other day. You’ve seen those diagrams, right? The ones that look like a slightly sad, deflated beach ball surrounded by a bunch of squiggly lines? Anyway, this particular diagram had these little… things… embedded in its outer wall. They looked like tiny, stylized door handles, or maybe even weird protein pretzels. And it got me thinking. How do these things, these integral membrane proteins, actually stay put in the cell membrane? It's not like they're glued in, and they’re definitely not just floating around aimlessly. They’re integral, meaning they’re a fundamental part of the membrane's structure and function. And the key to their persistence, I discovered, lies in this incredibly cool, and let’s be honest, a little bit weird, part of them called the transmembrane domain.

Think about it. The cell membrane is basically a lipid bilayer. It's a double layer of fatty molecules, like a greasy sandwich. Now, if you tried to stick a regular old protein, the kind that hangs out in the watery cytoplasm, into this greasy environment, it would probably just get rejected. It’d be like trying to dunk a water balloon into a vat of oil – it just wouldn’t mix. The parts of a protein that like water (hydrophilic) would want to avoid the oily membrane, and the parts that like oil (hydrophobic) would be fine, but the whole thing would probably just… fall apart.

But integral membrane proteins are different. They’re built for this oily environment. They have these special sections, these transmembrane domains, that are perfectly adapted to be embedded within the lipid bilayer. It’s their way of saying, "Hey, membrane, we belong here!"

The "Grease-Proof" Section

So, what makes these transmembrane domains so special? Well, it all comes down to their chemistry. You see, the inside of the cell membrane is incredibly hydrophobic. It’s all about those fatty acid tails of the phospholipids. They’re designed to repel water, which is why the membrane acts as such a good barrier, keeping the inside of the cell separate from the outside. Now, imagine trying to build something that can happily sit in this oily wonderland without being pushed out.

That’s where the transmembrane domain shines. Instead of having lots of charged or polar amino acids, which would interact with water, these regions are packed with hydrophobic amino acids. Think of amino acids like Alanine, Valine, Leucine, and Isoleucine. These guys have got those nice, non-polar side chains that just love to hang out with other non-polar things, like those lipid tails. They're like the ultimate hydrophobic buddies.

So, when an integral membrane protein is being made, and it needs to find its home in the membrane, these hydrophobic regions of its transmembrane domain will naturally gravitate towards the lipid bilayer. It's a matter of thermodynamics, really. The system as a whole becomes more stable when these hydrophobic bits are tucked away in the membrane, away from the watery environment.

It’s kind of like how oil and water don’t mix. If you have a molecule with both oily and watery parts, the oily parts will try to clump together to avoid the water, and the watery parts will do the same. The transmembrane domain is the protein's way of having a big, oily "clump" that just fits perfectly into the oily membrane.

Not All Transmembrane Domains Are Created Equal (But They All Get the Job Done)

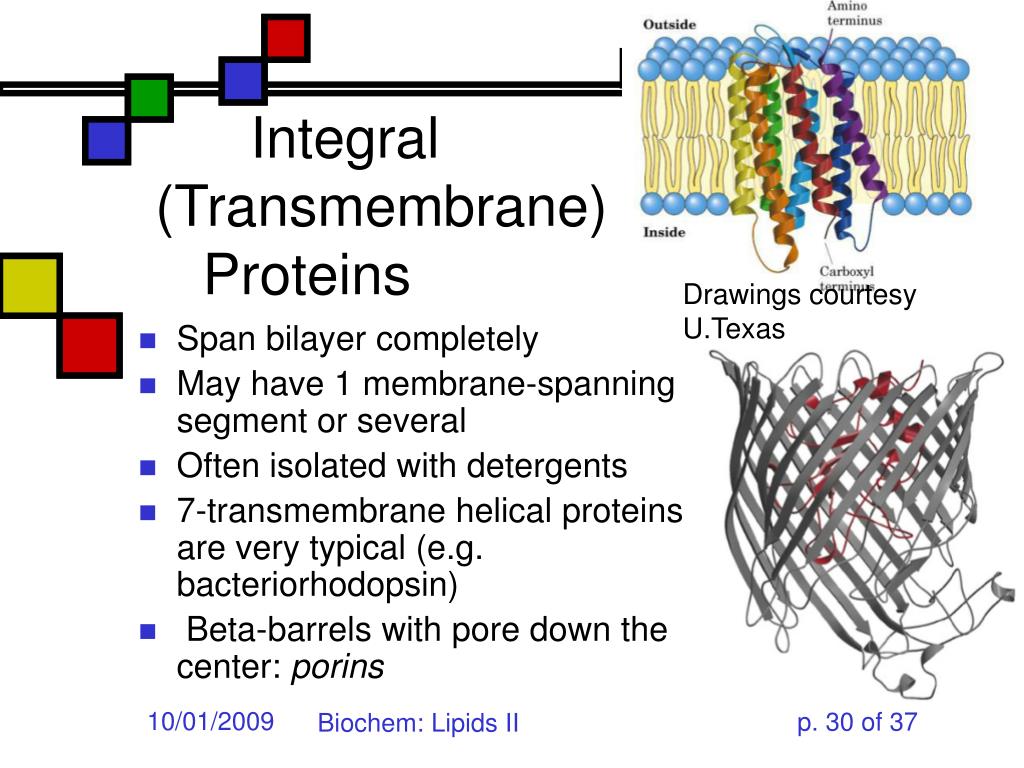

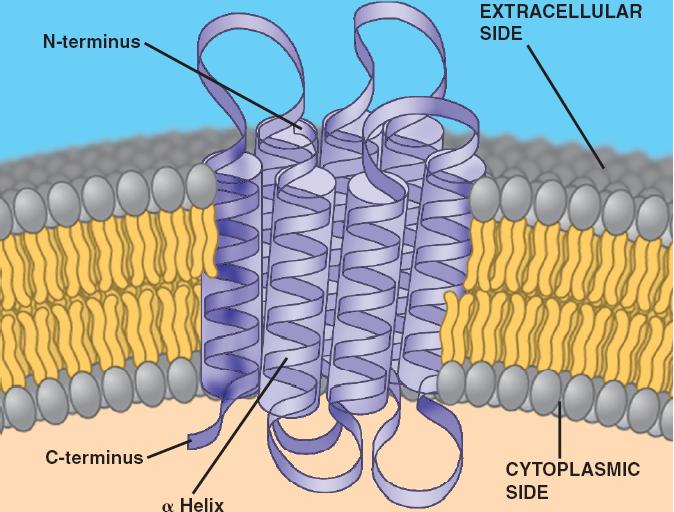

Now, while the core principle is the same – hydrophobic amino acids for a hydrophobic environment – there are different ways these transmembrane domains can be structured. The most common type, and the one you’ll see in many textbooks, is the alpha-helical transmembrane domain. Imagine a coiled-up spring. That’s kind of what an alpha-helix looks like. In this structure, the hydrophobic side chains of the amino acids stick out from the helix, facing outwards towards the lipids. It’s a really efficient way to span the membrane.

Then you have beta-barrel transmembrane domains. These are a bit more unusual, often found in proteins that span the outer membrane of bacteria, or in things like porins (which act as channels for small molecules). Instead of a single helix, a beta-barrel is formed by a sheet of beta-strands that fold up into a barrel shape. The outside of this barrel is hydrophobic, interacting with the lipids, while the inside can be lined with more polar amino acids to form a channel through the membrane. Pretty neat, huh?

But the key takeaway is the hydrophobicity. Whether it’s an alpha-helix or a beta-barrel, the parts that are in the membrane have to be good at interacting with lipids. It's their ticket to staying put.

The Protein's "Anchor"

So, why is this transmembrane domain so important, beyond just keeping the protein in place? Well, it acts as a crucial anchor. Imagine you have a boat. The anchor is what keeps it from drifting away. Similarly, the transmembrane domain anchors the rest of the protein within or across the membrane. The parts of the protein that stick out into the cytoplasm or the extracellular space are where a lot of the protein's action happens – binding to other molecules, catalyzing reactions, or transporting substances.

Without that strong anchor, these functional parts would be useless if the protein kept on moving around or falling out of the membrane. The transmembrane domain provides the stability needed for the protein to do its job. It's like the foundation of a house – you need a solid base for everything else to function properly.

Think about ion channels, for example. These proteins have to form a pore through the membrane to let specific ions pass. The transmembrane domain forms the walls of this pore, and it’s the hydrophobic nature of these walls that helps to create the environment for ion transport. If those walls weren't hydrophobic and anchored in the membrane, the channel wouldn't be able to do its job of selectively letting ions through.

Beyond Simple Anchoring: Signaling and Structure

But the transmembrane domain isn’t just a passive anchor. In many cases, it plays a more active role. It can be involved in protein-protein interactions within the membrane. Imagine two integral membrane proteins needing to work together. Their transmembrane domains might interact with each other, helping to form protein complexes. This is crucial for a lot of cellular processes, like signal transduction, where a signal from outside the cell needs to be relayed inside.

Sometimes, the transmembrane domain itself can even be involved in signaling. Certain stimuli can cause changes in the conformation of the transmembrane domain, which can then trigger changes in the rest of the protein, leading to a cellular response. It's like a little sensor that's embedded in the membrane.

And let's not forget the structural role. Integral membrane proteins, with their transmembrane domains, are integral to the very structure of the cell membrane. They contribute to its fluidity, its stability, and its ability to form specialized domains within the membrane. They're not just passengers; they're builders.

The "Edge" Problem: Transmembrane Domains and Their Boundaries

Now, here’s a little detail that always blows my mind. The transmembrane domain has to transition from being in the greasy lipid bilayer to being in the watery cytoplasm or extracellular space. How does that happen without the protein just falling apart? It’s all about the amino acids at the edges of the transmembrane domain.

These "boundary" amino acids are often a bit more polar than the core hydrophobic ones. They act as a sort of bridge, gradually easing the protein from the hydrophobic environment of the membrane to the hydrophilic environment outside. It's a clever design, isn't it? Like a perfectly engineered ramp.

This transition is also where we find the signals that tell the cell machinery where to insert the protein into the membrane in the first place. It's a complex choreography!

A World of Integral Proteins: Diversity and Function

The diversity of integral membrane proteins is staggering. We have:

- Receptors: These proteins bind to signaling molecules (like hormones) on the outside of the cell and transmit that signal inside. Their transmembrane domains are key for anchoring them and sometimes for mediating the conformational change that signals transduction.

- Transporters: These proteins move specific molecules across the membrane, either passively or actively. Think of glucose transporters or ion pumps. Their transmembrane domains often form the channels or gates for these molecules.

- Enzymes: Some enzymes are embedded in the membrane and catalyze reactions right there.

- Adhesion molecules: These proteins help cells stick to each other or to the extracellular matrix. Their transmembrane domains are critical for this stable connection.

And the number of transmembrane domains a protein has can vary too! Some proteins just have one, spanning the membrane once. Others, like many transporters and receptors, have multiple transmembrane domains, weaving back and forth like a complex tapestry. This multi-spanning arrangement allows for more intricate channel formation or receptor activation.

Consider a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR). These are some of the most studied proteins in our bodies. They typically have seven transmembrane alpha-helices. This arrangement creates a pocket on the extracellular side for ligand binding and a conformational change on the intracellular side that activates a G-protein. The transmembrane domains are absolutely central to this entire signaling cascade!

The Implications for Science and Medicine

Understanding the transmembrane domain is not just a neat biological puzzle; it has huge implications for science and medicine. Many drugs work by targeting integral membrane proteins. If you can understand how these proteins are embedded in the membrane, and how their transmembrane domains contribute to their function, you can design better drugs to modulate their activity.

For instance, many drugs for conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes, and even certain cancers target membrane receptors or transporters. The design of these drugs often involves considering how they will interact with the transmembrane domain and the surrounding lipid environment. It's about getting the drug to the right place and making it interact with its target effectively.

Also, mutations in the genes encoding integral membrane proteins can lead to a variety of diseases. These mutations can affect the folding, insertion, or function of the transmembrane domain, disrupting normal cellular processes. Studying these mutations helps us understand disease mechanisms and potentially develop new therapies.

It’s a fascinating field, and the humble transmembrane domain, this seemingly simple hydrophobic segment, is at the heart of so much of it. It’s the unsung hero, the silent anchor, the essential link that allows these vital proteins to do their jobs within the dynamic, ever-changing landscape of the cell membrane. So, the next time you see one of those cell diagrams, give a little nod to those embedded proteins and their amazing transmembrane domains. They’re the ones holding the fort!