The Relationship Between Loci And Linkage That Morgan Described Is

Imagine a detective story, but instead of a stolen jewel, the mystery is about how traits get passed down from parents to their kids. That’s kind of what we’re diving into today, and it’s all thanks to a super smart scientist named Thomas Hunt Morgan. He wasn't just staring at spreadsheets; he was observing tiny fruit flies, and what he found totally changed how we think about genes.

So, what’s this big idea about loci and linkage? Let’s break it down without getting too bogged down in fancy jargon. Think of your genes like a giant instruction manual for building you. These instructions are written on long strands called chromosomes.

Now, each specific instruction, like the one for eye color or wing shape in our fruit fly friends, has its own special spot on a chromosome. This spot? That’s what scientists call a locus (plural: loci). You can think of it like a specific page and line number in that instruction manual. So, the locus for eye color is on chromosome X, let’s say on page 5, line 3. The locus for wing shape might be on page 10, line 7.

Makes sense, right? So, loci are just the addresses of our genes on the chromosomes. Easy peasy. But here’s where it gets really juicy, and why Morgan’s work was such a blast to discover:

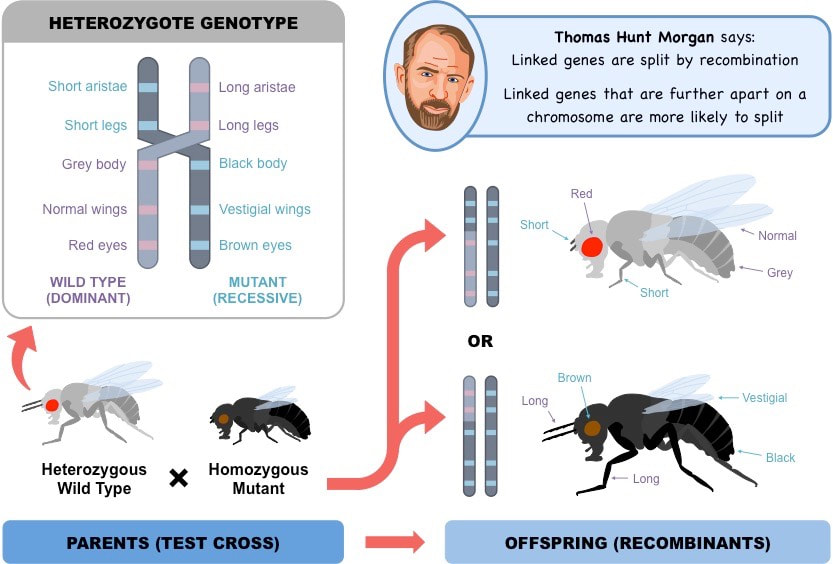

What if two different instructions, two different genes, are located really, really close to each other on the same chromosome? Like, imagine they’re on the same page and line in our instruction manual. Or even better, they’re right next to each other on the same line!

This is where linkage comes in. When genes are close together on the same chromosome, they tend to get inherited together. It's like they're best buddies, holding hands as the chromosomes get passed down from parent to offspring. So, if one gene for, say, a certain hair color is linked to a gene for a specific nose shape, you’re more likely to see both those traits appear together in the next generation.

Thomas Hunt Morgan was studying these little guys called fruit flies. Why fruit flies? Well, they reproduce super fast, have lots of offspring, and their genetics are pretty straightforward to observe. Plus, they’re kind of cute in a quirky, fly-like way!

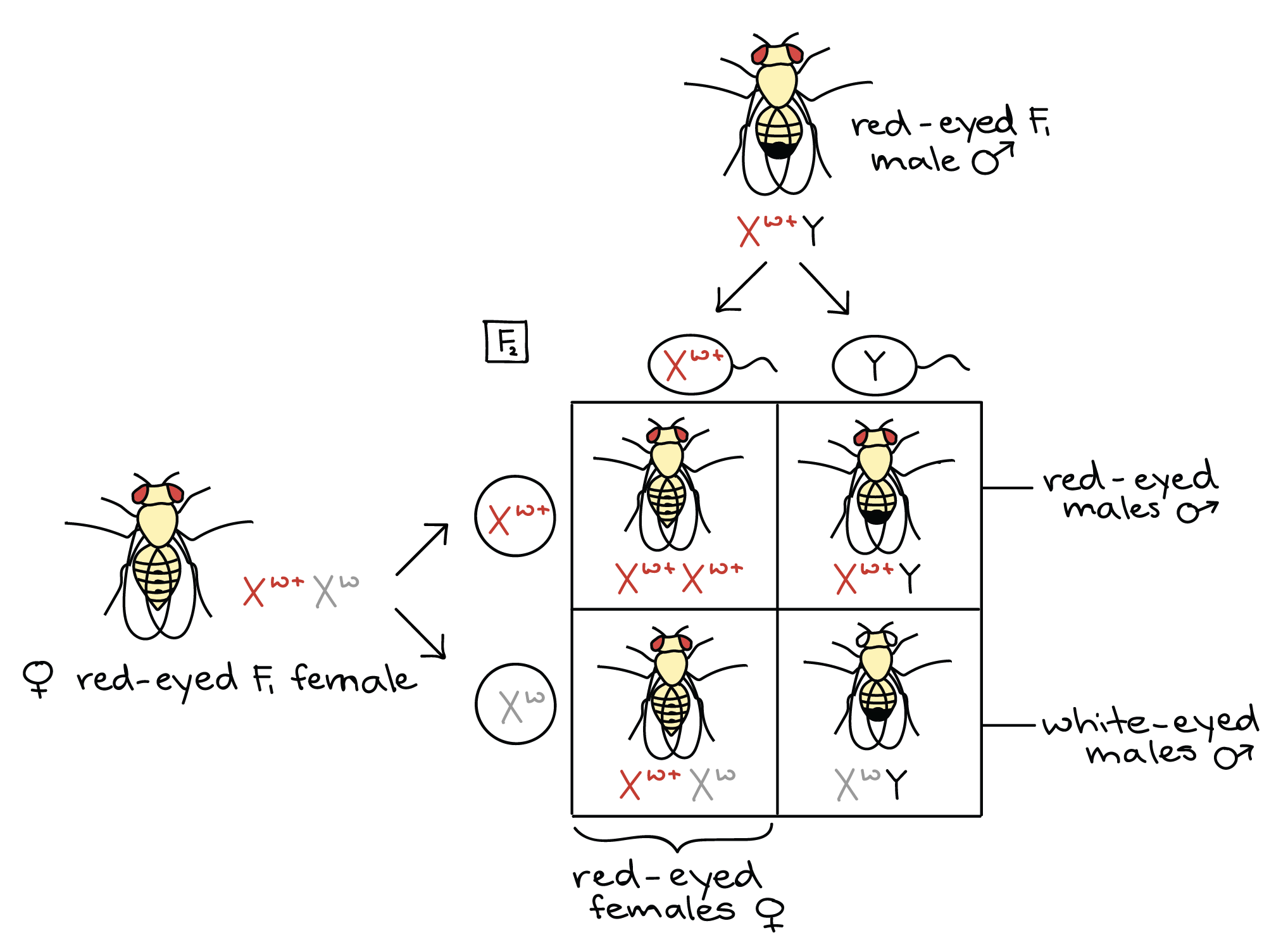

He noticed that certain traits in fruit flies always seemed to pop up together. For example, if a fly had a specific eye color mutation, it also seemed to have a mutation in its wing structure. He started thinking, "Hmm, could these genes be physically located near each other on the same chromosome?" This was a groundbreaking idea because, at the time, people thought genes just sort of shuffled around independently.

Morgan’s experiments showed that genes weren't just floating around randomly. They were organized on chromosomes, and their physical proximity mattered. This discovery was like finding a treasure map for how inheritance worked. Instead of just knowing that traits were inherited, he started showing us how and where on the chromosome these traits lived.

What makes this so entertaining is the detective work involved. Morgan and his team weren't just passively observing; they were actively crossing different strains of fruit flies and meticulously recording the results. They were looking for patterns, for deviations from the expected, and those deviations were the clues that pointed towards linkage.

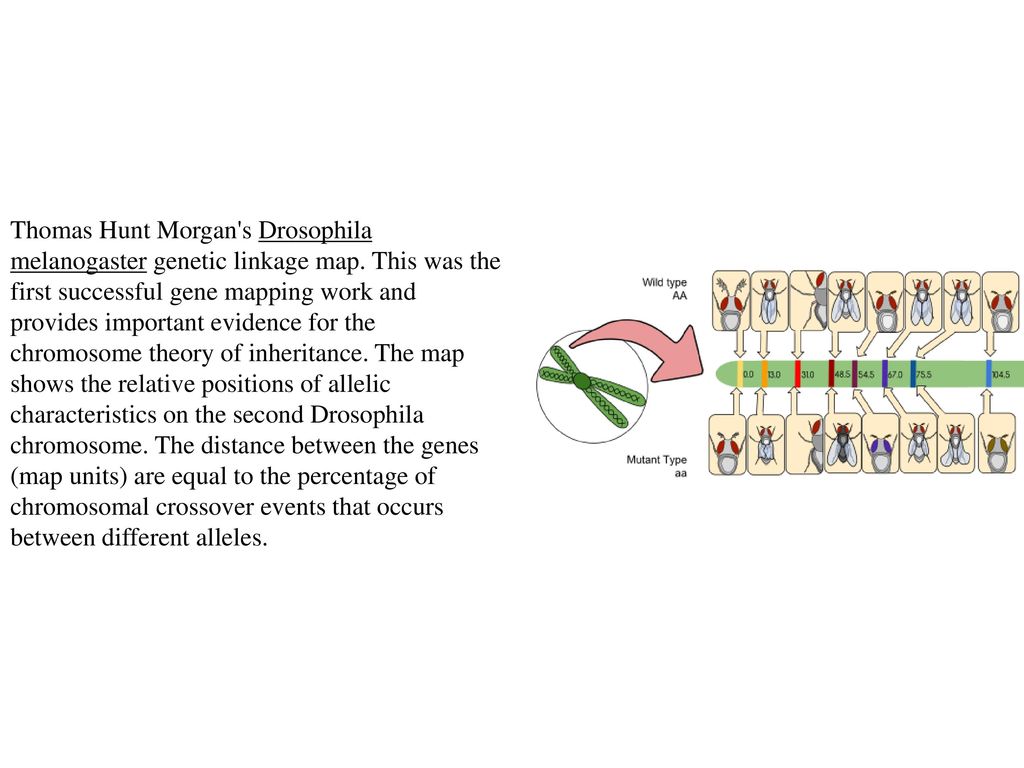

Think about it: they were basically drawing maps of the fruit fly chromosomes, figuring out the order of genes and the distances between them. It was like building the first-ever genetic roadmaps! And the tool they used to figure out these distances? It’s called recombination. Sometimes, during the process where chromosomes are passed down, they can swap small segments of DNA. This is like a little mix-and-match. The farther apart two genes are on a chromosome, the more likely it is that a swap will happen between them, breaking their linkage. But if they're super close, that swap is less likely to occur right in the middle of them.

So, Morgan could see how often traits got separated. If they were rarely separated, he knew they were tightly linked, meaning they were probably right next to each other. If they were separated more often, he knew there was a bit more "real estate" between them.

This is what makes Morgan's contribution so special. He didn't just confirm that genes existed; he showed us they had physical locations and that these locations influenced how they were inherited. He gave us the concept of gene mapping. We could start to predict, with a certain degree of accuracy, how likely it was that certain traits would be passed down together.

It’s a bit like understanding that if you want to grab two specific books from a bookshelf, it’s much easier if they're right next to each other than if they're at opposite ends. Morgan's work provided the foundation for understanding this “closeness” of genes on chromosomes.

So, next time you hear about genetics, remember Thomas Hunt Morgan and his buzzing fruit flies. He turned the abstract idea of inheritance into a tangible, map-able reality. It’s a story of observation, deduction, and the incredible power of looking closely at the smallest of creatures to understand the biggest of biological mysteries. It’s a tale that still resonates today in everything from understanding inherited diseases to developing new crops!