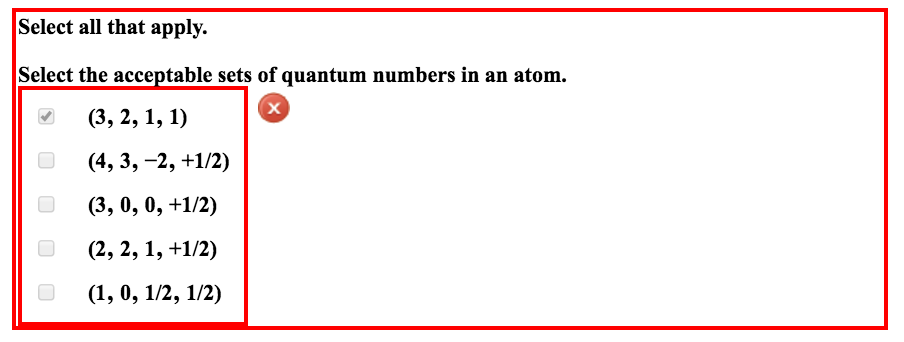

Select The Acceptable Sets Of Quantum Numbers In An Atom

Ever wondered what makes atoms, the tiny building blocks of everything, tick? It’s not just random buzzing! Atoms have a surprisingly organized internal life, and understanding it is like unlocking a secret code to the universe. If you’ve ever been curious about how electrons arrange themselves within an atom, then you’re in for a treat! We’re about to dive into the fascinating world of quantum numbers, which are basically the atom's personal addresses for its electrons. Think of it as a fun scavenger hunt where we learn how to find these elusive subatomic particles. It's not just for scientists in labs; grasping these concepts can give you a whole new appreciation for the magic that happens at the smallest scales, from the colors of a sunset to the way your phone works.

The Atom's Digital Fingerprint: Unpacking Quantum Numbers

So, what exactly are these quantum numbers? Imagine an atom as a multi-story building, and electrons are the residents. To find any resident, you need their apartment number, floor, and even the specific room they're in. In the atomic world, these "addresses" are provided by four special numbers: the principal quantum number, the angular momentum quantum number, the magnetic quantum number, and the spin quantum number. Each electron in an atom has its own unique set of these four numbers, a bit like a digital fingerprint that tells us where it lives and how it behaves.

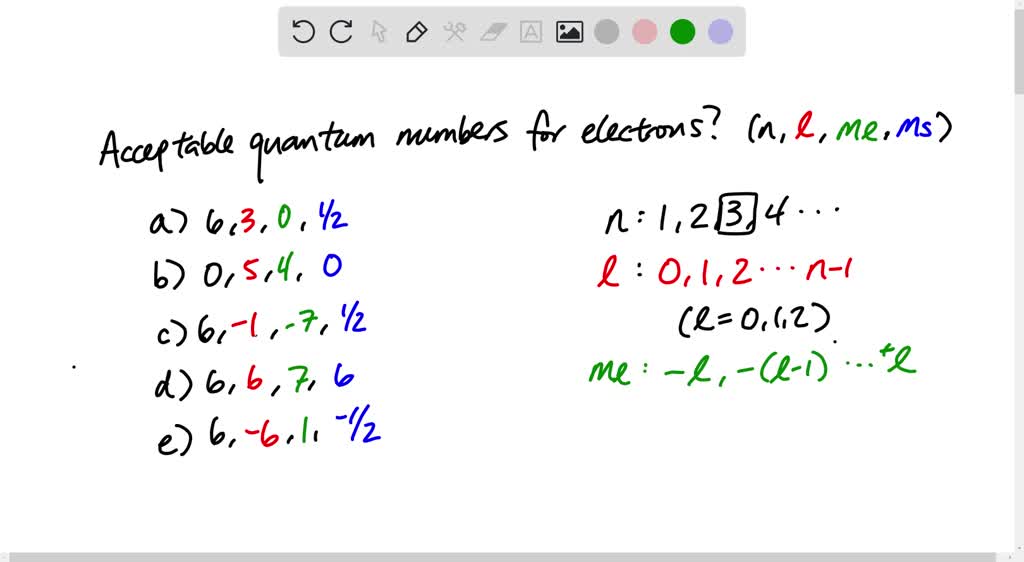

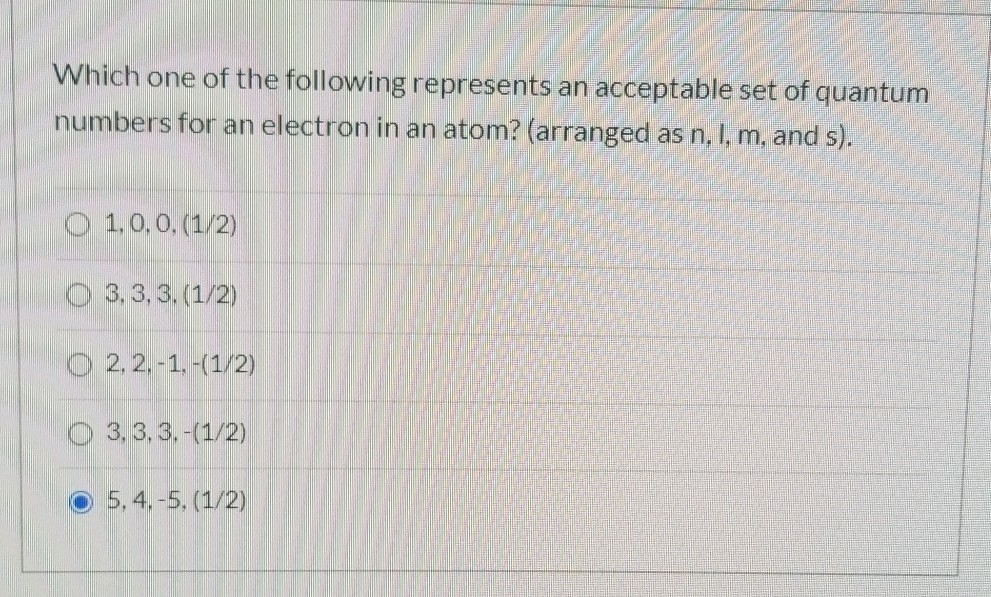

The principal quantum number, often symbolized by a lowercase ‘n’, tells us the main energy level an electron is in. Think of it as the floor number in our atomic apartment building. Higher numbers mean higher energy levels and, generally, electrons further away from the atom's nucleus. So, an electron with n=1 is on the lowest energy floor, closest to home base, while an electron with n=3 is on a higher, more energetic floor.

Next up is the angular momentum quantum number, represented by ‘l’. This number describes the shape of the electron's orbital, which is the region around the nucleus where the electron is most likely to be found. For a given energy level (n), l can take values from 0 up to n-1. We often use letters to represent these shapes: l=0 corresponds to an 's' orbital, which is spherical; l=1 corresponds to a 'p' orbital, which is dumbbell-shaped; l=2 corresponds to a 'd' orbital, with more complex shapes; and l=3 corresponds to an 'f' orbital, with even more intricate forms. It’s like saying an electron lives on the third floor (n=3) and has a spherical room (l=0, an 's' orbital).

Then we have the magnetic quantum number, denoted by ‘ml’. This number specifies the orientation of an orbital in space. For a given value of l, ml can range from -l to +l, including 0. For example, if an electron is in a 'p' orbital (l=1), there are three possible orientations: ml = -1, 0, +1. These are often described as the px, py, and pz orbitals, like three different rooms on the same floor, each pointing in a different direction. This is crucial because electrons in different orientations of the same subshell have the same energy.

Finally, there's the spin quantum number, symbolized by ‘ms’. Electrons are not just passive residents; they also spin! This spin creates a tiny magnetic field. The spin quantum number tells us the direction of this spin, which can be either 'up' or 'down'. We typically represent these as +1/2 and -1/2. This is a fundamental property, and it's responsible for a lot of the subtle behaviors of atoms. It's like each resident having a personal trait that helps distinguish them from others on the same floor and in the same type of room.

The Rules of the Game: Why Not All Combinations are Allowed

Now, for the fun part – figuring out which sets of these four quantum numbers are acceptable. Nature has some strict rules, and the most important one here is the Pauli Exclusion Principle. This principle states that no two electrons in an atom can have the exact same set of all four quantum numbers. This is why each electron needs its unique "address"! It means that in any given orbital (defined by n, l, and ml), you can only fit a maximum of two electrons, and they must have opposite spins (one +1/2 and one -1/2).

So, when we're asked to select acceptable sets of quantum numbers, we're essentially checking if a proposed set of four numbers violates any of these rules. For instance, if we have a set where n=2, l=2, ml=0, and ms=+1/2, we'd immediately know it's unacceptable. Why? Because the principal quantum number n=2 only allows for angular momentum quantum numbers l=0 and l=1. An l value of 2 is not permitted when n is 2.

Let's look at another example: n=1, l=0, ml=0, ms=+1/2. Is this acceptable?

- n=1 is fine.

- For n=1, l can only be 0 (since l goes from 0 to n-1). This is okay.

- For l=0, ml can only be 0 (since ml goes from -l to +l). This is okay.

- ms can be +1/2 or -1/2. This is okay.

Consider this set: n=3, l=1, ml=2, ms=-1/2.

- n=3 is fine.

- For n=3, l can be 0, 1, or 2. So, l=1 is fine.

- For l=1, ml can be -1, 0, or +1. So, ml=2 is not acceptable.

The beauty of understanding these rules is that it allows us to predict and explain the structure and behavior of elements. It's the foundation for everything from the periodic table to chemical bonding. So, next time you look at an atom, remember it’s not just a tiny ball, but a miniature universe with its own set of rules and its own unique electron addresses!