Rutherford's Gold Foil Experiment Established That ____.

Imagine you’re trying to figure out what’s inside a tightly wrapped gift box, but you can’t peek or even shake it too hard. That was kind of the pickle scientists were in a little over a hundred years ago. They knew atoms were the building blocks of everything, like LEGO bricks for the universe, but they had no clue what those tiny bricks looked like on the inside. It was like having a whole world of information, but it was all hidden behind a really, really stubborn wrapper.

Then along came a brilliant chap named Ernest Rutherford. This guy was basically a scientific detective, and he had a hunch about how to solve the mystery of the atom. He wasn’t content with just knowing atoms existed; he wanted to see their inner workings. Think of it like wanting to know if your favorite cookie has chocolate chips all the way through, not just on the surface. He needed a way to poke and prod without actually breaking the cookie.

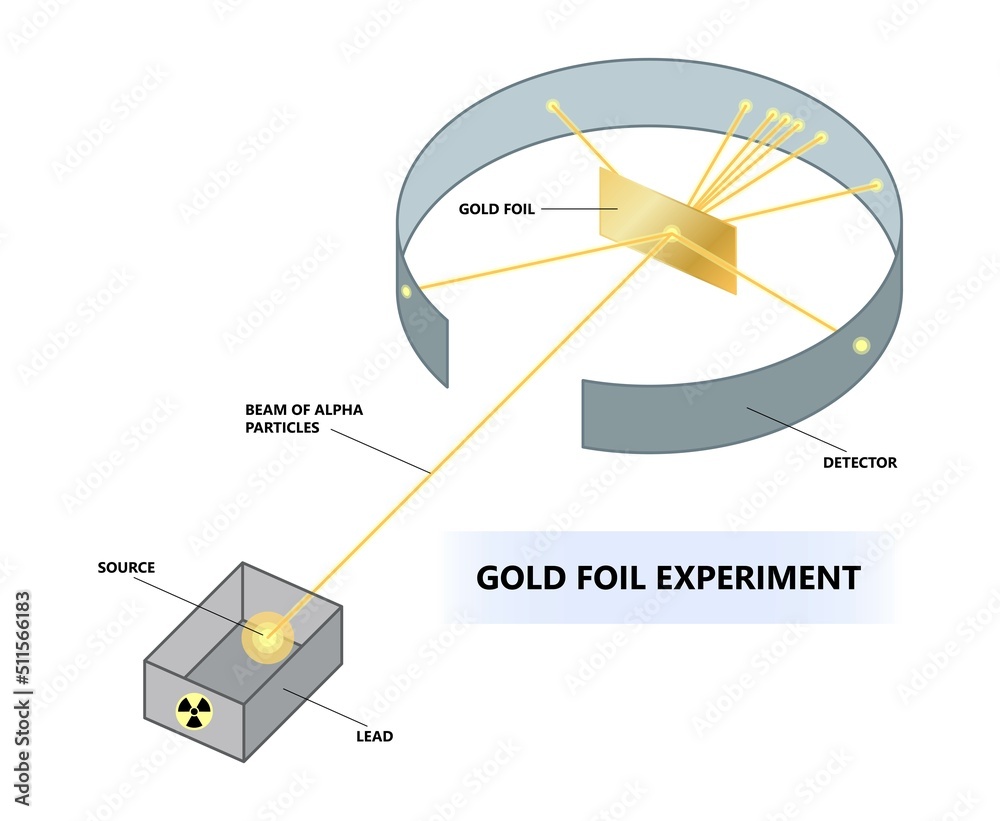

Rutherford’s big idea involved something called alpha particles. Now, these aren’t your average particles. Imagine them as super-tiny, positively-charged bullets, fired with incredible precision. He got his hands on a radioactive source – kind of like a tiny, energetic spitting machine – that conveniently spat out these alpha particles. His plan was to shoot these little bullets at something incredibly thin, something so thin you’d barely feel it if it brushed past you.

His target? A sheet of gold foil. Why gold, you ask? Well, gold is famously malleable. You can hammer it out so thin that it’s practically see-through. Seriously, the stuff is so thin it’s almost like it’s not there. It’s like trying to see through a cobweb spun by a very dedicated spider, but even thinner. This ultra-thin gold foil was perfect because Rutherford figured it would have a very, very thin layer of gold atoms for his alpha particles to interact with. He wanted to minimize the chances of a bullet bouncing off a whole bunch of atoms at once, which would be like trying to understand a single grain of sand by throwing a bowling ball at a beach.

So, Rutherford set up his experiment. He had his alpha particle spitting machine, his ridiculously thin gold foil, and then, crucially, a screen around it all. This screen was special because when one of those tiny alpha particles hit it, it would give off a little flash of light. Think of it like glow-in-the-dark paint, but much more sensitive. Every time an alpha particle smacked into the screen, FLASH! A little tiny light show.

The idea was simple: shoot the alpha bullets at the gold foil and see where they ended up on the screen. Most of the time, they were like little energetic toddlers who’d run straight through an open doorway. They’d zip right through the gold foil without a hitch, hitting the screen on the other side. This was exactly what Rutherford and his colleagues expected. They figured atoms were like fuzzy, spread-out clouds of positive charge with electrons (which are negatively charged) floating around in them. So, they thought the alpha particles, being positive, would just kind of push through this diffuse cloud, maybe get nudged a little, but mostly carry on their merry way.

But then, things got weird. Like, really weird. Imagine you’re throwing tiny ping pong balls at a giant, fluffy pillow. You’d expect most of them to go right through, maybe sink in a little. But what if, every now and then, one of those ping pong balls shot back at you? That’s the kind of bizarre outcome Rutherford observed.

A small fraction of the alpha particles, and this is the mind-blowing part, were deflected. Not just a little nudge, but some were sent flying off at crazy angles. And then, the ultimate shocker: a tiny, tiny handful of them, maybe one in 8,000, actually bounced straight back. It was like throwing that ping pong ball at the fluffy pillow and having it rebound and smack you right in the forehead.

Rutherford himself famously described it as being as "inconceivable as if you fired a 15-inch shell at a piece of tissue paper and it came back and hit you." Can you picture that? It’s the stuff of absolute disbelief! It’s like expecting your cat to ignore a laser pointer dot, and instead, it leaps across the room, catches the laser pointer, and brings it back to you, demanding belly rubs. Utterly unexpected.

This completely threw their original understanding of the atom out the window. The fuzzy cloud model just couldn’t explain why these positively charged bullets were being violently repelled or even sent on a round trip. It was like trying to explain how a ghost could knock over a vase – the existing rules just didn't apply.

So, what was going on? Rutherford and his team, after scratching their heads and probably having a good few cups of tea, started to piece it together. They realized that the atom couldn’t be a fuzzy, diffuse cloud. Instead, the vast majority of the atom must be empty space. Think of it like a huge, empty stadium. Most of the space inside is just air.

But somewhere, smack dab in the middle of this stadium, there had to be something incredibly small, incredibly dense, and positively charged. This was the atomic equivalent of a tiny, but super-heavy, bowling ball sitting at the center of that empty stadium. When the alpha particles, with their positive charge, got close to this central, positively charged core, they experienced a powerful repulsive force. It was like two magnets with the same poles trying to push each other away, but on a microscopic scale and with a lot more oomph.

This tiny, dense, positively charged center of the atom was what Rutherford named the nucleus. It was like finding the hidden treasure chest in a pirate map that you thought was just empty beach. And here's the kicker: this nucleus, despite being where all the positive stuff and most of the atom's mass was packed, was incredibly, unbelievably tiny. It’s like finding out that the entire population of a bustling city is actually crammed into a single, tiny apartment building.

The electrons, those negative charges, were still there, but they were whizzing around this nucleus, like tiny gnats orbiting a very, very small, very powerful sun. Most of the atom, then, was this vast expanse of nothingness, the "empty space" between the nucleus and the orbiting electrons. This explained why most alpha particles zipped right through – they were just passing through the empty stadium, missing the tiny, dense nucleus and the speedy gnats.

The ones that got deflected? They were the unlucky bullets that happened to fly too close to the nucleus. The closer they got, the stronger the repulsion, and the more they got shoved off course. And the very few that bounced straight back? Those were the ones that practically hit the nucleus head-on. It was like a direct hit from a cannonball, forcing them to turn around and flee.

So, what did Rutherford’s Gold Foil Experiment establish, in a nutshell? It established that the atom has a small, dense, positively charged nucleus at its center, and that most of the atom is empty space.

This was a monumental shift in our understanding. Before this, atoms were thought of as more like plum puddings, with the positive charge spread out and the electrons embedded in it. Rutherford’s experiment, with its surprising deflections, showed that the atom wasn't a uniform blob at all. It was more like a miniature solar system, with a central sun (the nucleus) and planets (the electrons) orbiting it, with a whole lot of space in between.

It’s like going from thinking your house is just a big, slightly lumpy wall, to realizing it’s actually got a tiny, super-heavy furnace in the middle, and the furniture is all just floating around it at a distance. Suddenly, everything makes more sense, even though it’s also a bit mind-boggling.

This discovery was so important because it provided the foundation for all subsequent atomic physics. It paved the way for understanding how atoms interact, how elements behave, and even how we harness nuclear energy. It’s the bedrock of so much of modern science, all thanks to a bunch of tiny bullets, some super-thin gold, and a very observant scientist who wasn’t afraid to question what everyone else thought they knew. It’s a great reminder that sometimes, the most profound discoveries come from paying attention to the unexpected flukes, the tiny deviations from the norm, much like noticing a single oddly colored M&M in a bag of plain ones and wondering why it's there.