Prove That The Diagonals Of The Parallelogram Bisect Each Other

Hey there, fellow explorers of the geometric realm! Ever looked at a parallelogram and just felt a sense of calm, a certain... balance? Well, that feeling isn't just in your head. Parallelograms have this really neat property that makes them special, and today, we're going to gently pull back the curtain and see why. It’s like discovering a secret handshake between the shapes!

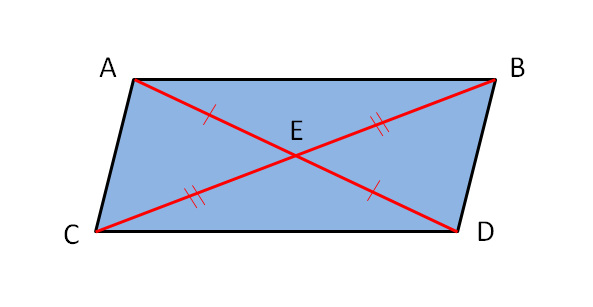

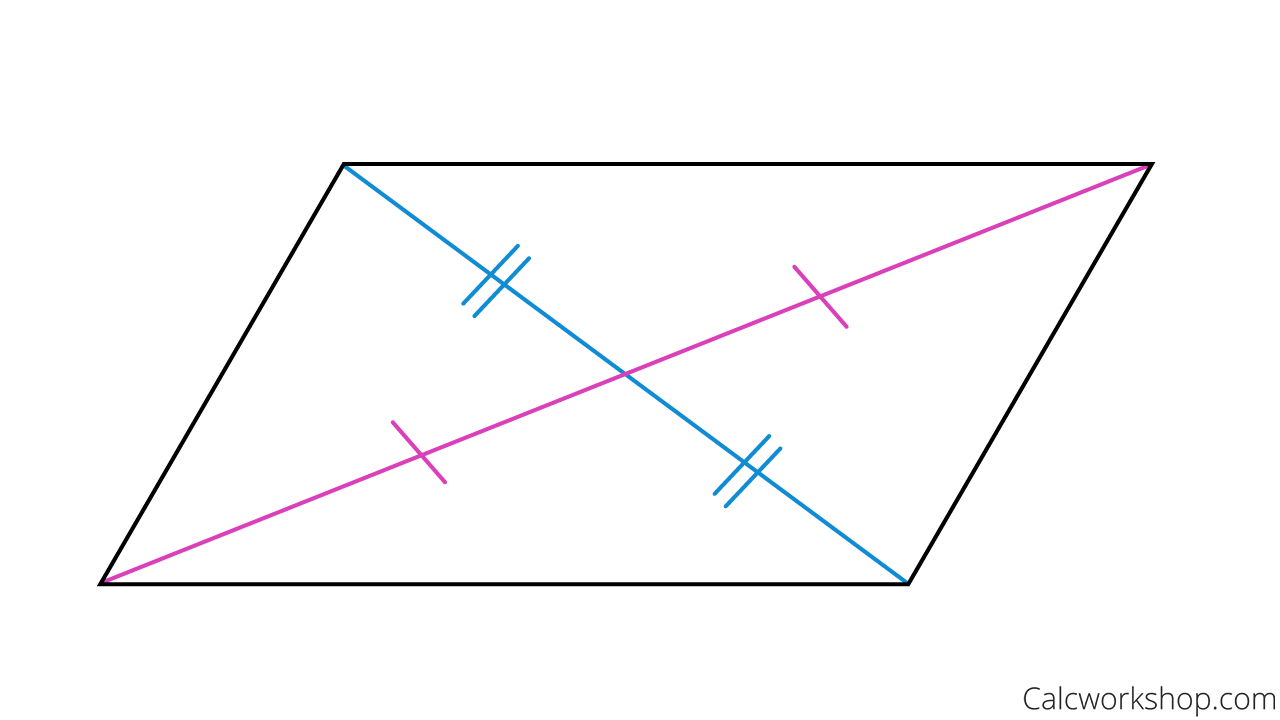

We're talking about the diagonals, those lines that stretch across the parallelogram from one corner to the opposite one. You know, the ones that look a bit like crossing swords? But instead of a duel, these swords do something much more harmonious. They actually meet right in the middle, and not just any middle, but the exact middle of both diagonals. Pretty cool, right?

So, how do we prove this? Now, I know "prove" can sometimes sound a bit intimidating, like you need a giant textbook and a magnifying glass. But honestly, it's more like a gentle puzzle, a bit of logical detective work. We're not going to get bogged down in super complex jargon. Think of it like figuring out a really satisfying magic trick. You see the trick, and then you understand how the magician did it. It's that kind of "aha!" moment we're aiming for.

Let's Get Our Shapes Together!

First things first, what exactly is a parallelogram? It's a four-sided shape, a quadrilateral, where opposite sides are parallel. That's the key word: parallel. Imagine train tracks – they go on forever and never touch. That's what opposite sides of a parallelogram are like. And because of this parallel-ness, the opposite sides are also the same length. It's like a perfectly matched set of twins, always the same size and always keeping their distance.

Now, let's draw one. Grab a piece of paper, or just picture it in your mind. You've got your top and bottom sides parallel, and your left and right sides parallel. Notice how the angles aren't necessarily square (like in a rectangle)? That's what gives it that charming, slightly slanty look. It’s like a tilted picture frame, but with a guaranteed geometric fairness.

Enter the Diagonals!

Okay, so we have our parallelogram. Now, let's draw those diagonals. Connect the top-left corner to the bottom-right, and then the top-right corner to the bottom-left. They’ll cross somewhere in the middle. The big question is: do they meet at their own midpoints? Does one diagonal slice the other exactly in half, and vice-versa?

Imagine you have two strings of equal length. If you lay them on top of each other and find the exact center of each, and then you could somehow attach them at their centers, that's kind of what we're expecting to happen with our diagonals. But why? Why should this specific shape, the parallelogram, behave this way?

The Magic of Congruent Triangles

Here's where the geometric detective work really kicks in. We're going to break down our parallelogram into some smaller, friendlier shapes: triangles! Remember triangles? They're the sturdy building blocks of geometry. When two triangles are congruent, it means they are absolutely identical in every way – same angles, same side lengths. Think of them as perfect twins, born from the same mold. If we can show that certain triangles within our parallelogram are congruent, we can use that to prove our diagonal-bisecting superpower.

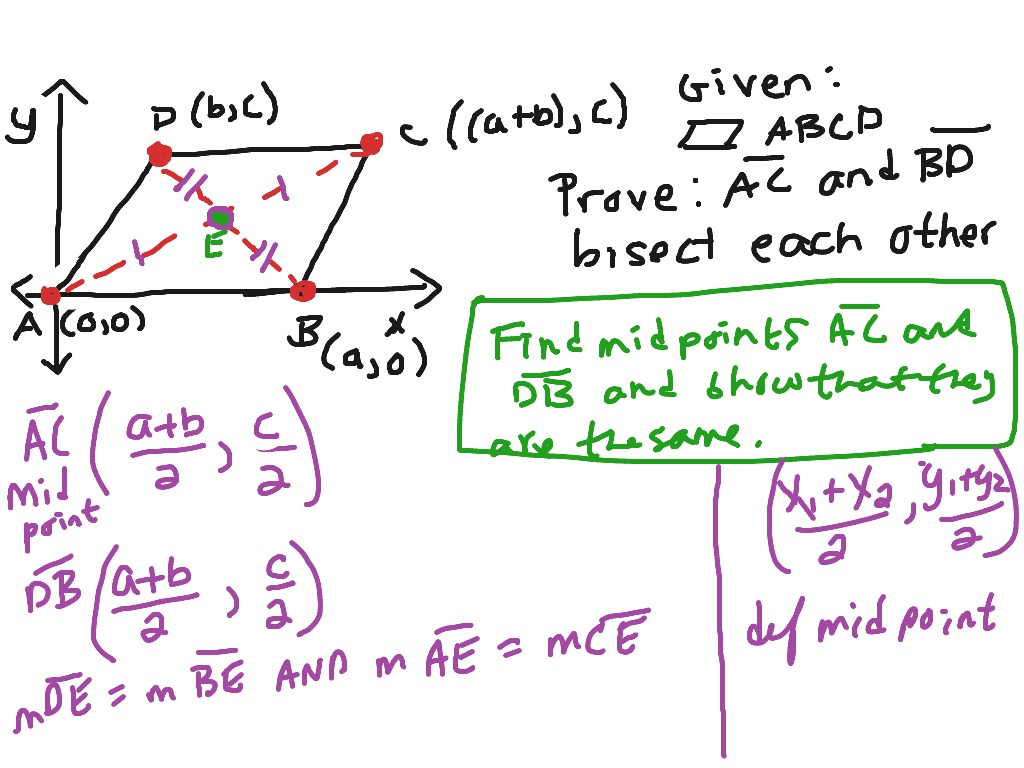

Let's look at our parallelogram, ABCD, with diagonals AC and BD intersecting at point E. Consider the two triangles, triangle ABE and triangle CDE. See them? They’re opposite each other, formed by one diagonal and two sides of the parallelogram.

What do we know about these triangles?

- We know that side AB is parallel to side DC (that's part of the definition of a parallelogram, remember?).

- We also know that side AB has the same length as side DC.

This is a great start, but it's not enough to say the triangles are congruent just yet. We need more matching bits!

Now, let's think about those parallel lines again: AB || DC. When a line crosses two parallel lines, it creates some special angle relationships. Imagine a zig-zag pattern. The angles in the "valleys" of the zig-zag are equal. These are called alternate interior angles.

So, if we look at diagonal AC crossing parallel lines AB and DC, the angle BAC (the one at corner A within triangle ABE) is equal to angle DCA (the one at corner C within triangle CDE). They're alternate interior angles!

Similarly, if we look at diagonal BD crossing parallel lines AB and DC, the angle ABD (the one at corner B within triangle ABE) is equal to angle CDB (the one at corner D within triangle CDE). More alternate interior angles!

Putting It All Together: The Proof!

So, let's recap what we've found for triangles ABE and CDE:

- Side AB = Side DC (opposite sides of a parallelogram are equal)

- Angle BAC = Angle DCA (alternate interior angles)

- Angle ABD = Angle CDB (alternate interior angles)

Now, look at what we have: we have a side and two angles in each triangle that match up perfectly. This is a classic triangle congruence rule: ASA (Angle-Side-Angle). If two angles and the included side of one triangle are equal to two angles and the included side of another triangle, then the two triangles are congruent. It's like having the same recipe and ingredients – you'll always get the same cake!

Since triangle ABE is congruent to triangle CDE, it means all their corresponding parts are equal. This is where the magic happens!

What are the corresponding sides in these congruent triangles? We've already used AB and DC. The other two pairs of corresponding sides are:

- AE = CE

- BE = DE

And there you have it! AE = CE means that point E is the midpoint of diagonal AC. It divides AC into two equal halves. And BE = DE means that point E is also the midpoint of diagonal BD. It divides BD into two equal halves.

So, the point where the diagonals intersect (point E) is the midpoint of both diagonals. They bisect each other!

Why Is This So Neat?

This property makes parallelograms so elegantly balanced. It's not just a coincidence; it's a fundamental characteristic that arises directly from the definition of a parallelogram. It's like a built-in symmetry feature.

Think about other shapes. In a kite, the diagonals are perpendicular, but one bisects the other, not both. In a general trapezoid, the diagonals don't necessarily bisect each other at all. The parallelogram is special. It's got this perfect, harmonious division happening.

It’s also a really useful fact! If you ever need to find the center of a parallelogram, you just draw the diagonals, and wherever they cross, that's your center. It's like a built-in GPS for the parallelogram's heart. It’s this quiet, reliable property that makes geometry so satisfying – the patterns are always there, waiting to be discovered.

So, next time you see a parallelogram, give it a nod. It's not just a tilted rectangle; it's a shape with a beautiful, proven secret: its diagonals are best friends who always meet in the middle, perfectly splitting each other. Isn't geometry just the coolest?