Metallic Character Decreases From Left To Right In A Period

Okay, so you know how sometimes you're at a potluck, and everyone brings something, right? You've got your super flaky, buttery croissants that just melt in your mouth – those are your metals. They're all eager to share, to give away their deliciousness, just like they're ready to give away their electrons. Easy peasy, happy to oblige.

Then, as you move down the table, you get to the stuff that's… well, not quite as outgoing. Maybe it's a really firm, slightly chewy bread. It's still pretty agreeable, but it's not quite as quick to be the star of the show. Think of these as the elements a little further along in the potluck, still friendly, but not desperate to share the limelight (or their electrons).

And then you get to the end of the table. You've got your super-dense, maybe a little bit crusty, sourdough. This bread is a bit of a hoarder. It holds onto its goodness, its texture, its very essence with a fierce grip. It's not giving anything away easily. It's practically saying, "Nope, this is mine." These are your non-metals. They're not mean, just… self-contained. They like to keep their electrons close to their chest, thank you very much.

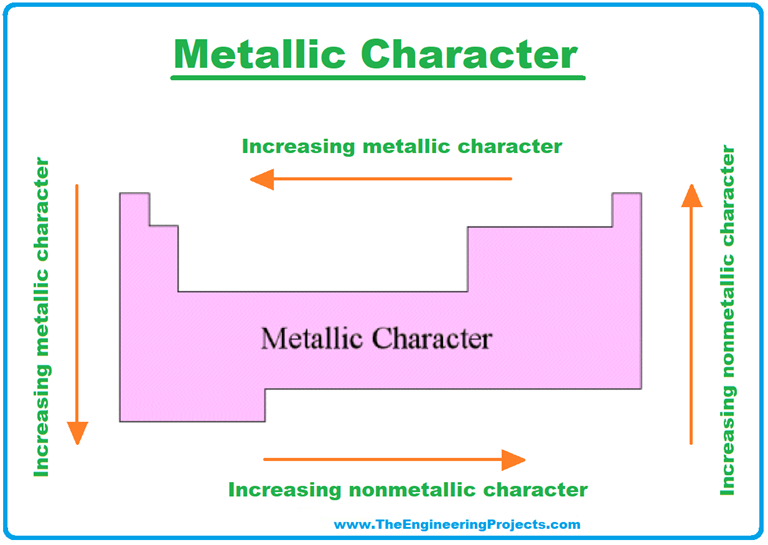

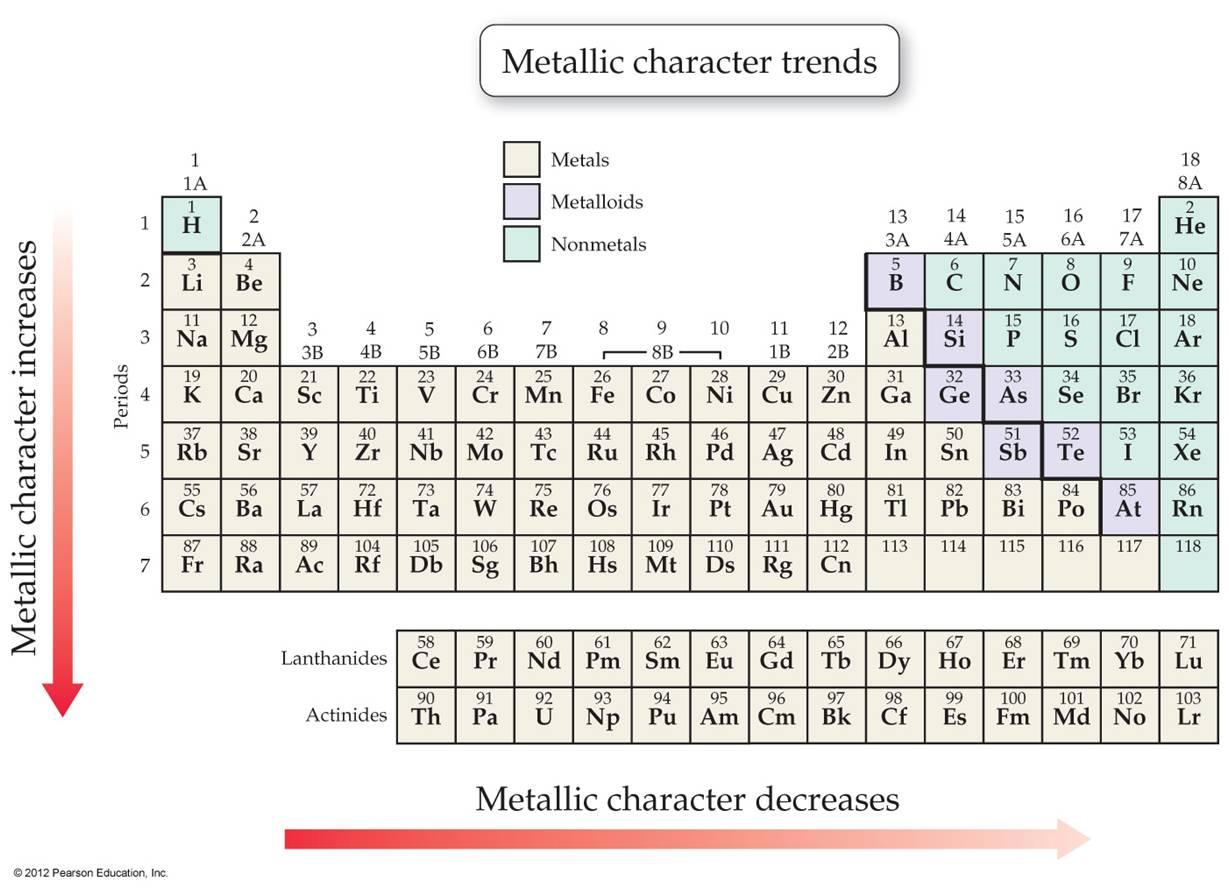

This whole potluck scenario, believe it or not, is a bit like what happens in the world of chemistry, specifically when we talk about metallic character. It's basically a fancy way of saying how much an element is like a friendly, outgoing metal. And just like at our imaginary potluck, this characteristic tends to change as you move across a row, or a period, on the periodic table.

Imagine the periodic table as a giant, well-organized buffet. You've got your rows, which we call periods, and your columns, called groups. When we're talking about metallic character decreasing from left to right within a period, we're essentially talking about a progression from the "super generous with the butter and flaky bits" types of elements to the "hold onto my crust like it's gold" types.

The Left Side: The Electron Givers

The elements on the left side of a period are your classic metals. Think of things like sodium (Na) and potassium (K). These guys are like that friend who always insists on paying for everyone's coffee, even when you tried to grab your wallet. They have this inherent desire to shed an electron, to be helpful, to form a positive ion. It's their jam. They're happy to be oxidized, as the chemists like to say, which just means they're readily giving up those precious electrons.

It's like they're at the buffet and they see a plate of something amazing, but it's a bit far to reach. So, they just hand a piece over to someone closer. "Here, you take it! I'm good." This electron-giving business makes them highly reactive, often in a way that's really useful. Think of how metals conduct electricity – they're basically channeling those freely moving electrons, like a highway of tiny, energetic delivery trucks.

They're the life of the party, always ready to mingle and share. This willingness to give away electrons is the hallmark of metallic character. They're electropositive, meaning they tend to have a positive charge when they form compounds, because they’ve lost their negative electron friends. It’s like they’re shedding baggage and feeling lighter, ready to embrace a new, positively charged identity.

So, if you’re looking for an element that's going to be super eager to donate, super malleable, and super conductive, you're going to want to hang out on the far left of any given period. These are your true blues of the metallic world, your absolute champions of electron-sharing.

Moving Towards the Middle: A Bit More Reserved

Now, as you start to inch your way towards the middle of the period, things get a little more… nuanced. Elements here aren't quite as gung-ho about giving away electrons. They're not completely opposed to it, but they're not actively seeking opportunities to do so either. Think of it as moving from someone who insists on buying you lunch to someone who says, "Oh, you want to split the appetizer? Sure, sounds good."

They might participate in electron exchange, but they're a bit more discerning. They might even be open to sharing an electron, rather than outright giving it away. This is where you start to see elements that can act as both metals and non-metals, the so-called metalloids. They're the Switzerland of the chemical world, trying to play nice with everyone.

Their metallic character is diminished. They're not as prone to forming positive ions. Instead, they might engage in covalent bonding, where electrons are shared, rather than ionic bonding, where they're transferred. It's like they're saying, "Let's both chip in and buy this thing together," instead of, "Here, I'll get it for you."

These elements are like the quiet, dependable folks at the party. They're not going to hog the dance floor, but they're definitely willing to chat and participate. Their electron behavior is a bit of a mixed bag, reflecting their position between the outgoing metals and the introverted non-metals. They're the wallflowers who are also surprisingly good conversationalists.

The Far Right: The Electron Hoarders

And then you arrive at the far right of the period. Welcome to the land of the non-metals! These are your halogens (like fluorine, F, and chlorine, Cl) and your noble gases (like neon, Ne, and argon, Ar). These elements are the polar opposite of our electron-giving metals. They are clingy. They are electron-avid.

Imagine going to that potluck, and the person at the end of the table has this amazing, perfectly golden piece of pie. You ask for a slice, and they just… hold it tighter. They're not going to give it away. In fact, they're probably eyeing your plate, wondering if they can snag a crumb from you. These are your non-metals.

They have a really strong attraction for electrons. They want to gain electrons to achieve a full outer shell, which makes them nice and stable. This is their ultimate goal, their chemical nirvana. They're not about giving; they're about taking (or, more accurately, attracting and holding onto). This strong pull on electrons is called electronegativity, and it's sky-high on the right side of the period.

So, the metallic character here is practically non-existent. It's like asking a cat to fetch your slippers – it's just not in their nature. These elements tend to form negative ions because they've snagged extra electrons. They're the ones who are always looking to complete their electron set, to feel whole and stable. They're the ultimate hoarders, but in a way that makes them chemically very interesting.

And the noble gases? They're like the people at the party who brought their own perfectly sealed container of snacks and are just enjoying them quietly in the corner, not interacting with anyone else's food. They already have a full set of electrons, so they're super stable and have virtually no metallic character. They're the ultimate introverts, content in their own electron-filled bubbles.

Why Does This Happen? The Nuclear Pull

So, what's the reason behind this gradual shift from generosity to hoarding as you move across a period? It all comes down to the nucleus, the central part of an atom, and the number of protons it has. As you move from left to right across a period, the number of protons in the nucleus increases.

Think of the nucleus as a really popular celebrity. The more famous (more protons) they are, the more attention (positive charge) they can command. This stronger positive charge in the nucleus has a greater pull on the electrons orbiting around it. The electrons, with their negative charge, are attracted to this stronger nuclear pull.

This increased attraction means that the outermost electrons are held more tightly. They can't just waltz off and join another atom as easily. For the metals on the left, the nucleus's pull is just strong enough to make them willing to part with an electron to get away from the nucleus's influence and feel more stable. But as you move to the right, the nucleus's grip tightens, making it much harder to pry those electrons loose.

It’s like a magnet. A weak magnet can barely hold onto a paperclip. A super-strong magnet can hold onto a whole stack of them. As you move across a period, the "magnet" of the nucleus gets stronger, and it holds onto its "paperclips" (electrons) more tenaciously. This increasing nuclear attraction is the fundamental reason why metallic character decreases.

The electrons in the inner shells act like a shield, but as the number of protons increases, the effective nuclear charge experienced by the valence electrons also increases, making them harder to remove. This subtle but powerful force dictates the chemical personality of the elements.

Putting It All Together: The Periodic Trend Party

So, the next time you're looking at the periodic table, you can imagine it as a grand party, with elements on the left being the super generous hosts, practically shoving appetizers (electrons) into your hands. As you move towards the right, the hosts become more reserved, then a little bit pickier about who they share with, and finally, on the far right, you have the guests who are meticulously guarding their own snacks and aren't keen on sharing at all.

This trend of decreasing metallic character from left to right in a period is one of the most fundamental and useful patterns in chemistry. It helps us predict how elements will behave, what kinds of compounds they'll form, and why certain materials are used for specific purposes. It’s the cosmic recipe for how the world is built, atom by atom.

It’s a neat little way to think about the abstract world of atoms and electrons. They’re not just random points on a chart; they have personalities, tendencies, and a whole lot of underlying order. And understanding these trends, like the gradual fading of metallic character, gives us a peek into that order, making the universe just a little bit more understandable, and dare I say, even a little bit cooler.

So next time you see a shiny piece of metal, a crunchy piece of bread, or even just a conversation about atoms, you can wink and know that you're witnessing a little bit of that left-to-right, metallic character magic in action. It’s a beautiful, predictable dance, played out on the grand stage of the periodic table.