Mendel Performed Hybridizations By Transferring Pollen From The

Okay, so imagine this: you're a serious scientist, right? Like, a proper scientist with lab coats and maybe even a ridiculously large pair of spectacles. You're trying to figure out how things get passed down from parents to kids. Not human kids, mind you, but, like, plants. You know, where does a pea plant get its green color? Why is one bean a giant and the other, well, a bit on the shy side in terms of size? It’s a bit like trying to guess what your own kids will look like. Will they have your nose? Your mom’s eyes? Or a hilarious combination of both that makes you chuckle every time you see them in the mirror?

Well, back in the day, this monk named Gregor Mendel was doing exactly that. And honestly, bless his heart, he didn't have fancy DNA sequencers or even a microscope that could show you much beyond a blurry blob. He had… peas. Lots and lots of peas. And a whole lot of patience. Seriously, you have to admire the dedication. I get antsy waiting for a kettle to boil, and he was out there, probably with a tiny paintbrush, playing Cupid for pea plants. Can you picture it? Mendel, humming a little tune, carefully dabbing pollen from one pea flower onto another. It’s so wonderfully… analog, isn't it?

This whole process, this deliberate act of shuffling the genetic deck, is called hybridization. And Mendel was, like, the OG of it all. He wasn't just randomly sticking stuff together and hoping for the best. Oh no. He was a scientist. He was meticulous. He chose specific traits to study, like pea color (yellow versus green) and pea shape (round versus wrinkled). Why these? Because they were distinct. There wasn't any fuzzy middle ground, you know? It was either one or the other, which, let’s be honest, makes the math a whole lot easier. Imagine trying to figure out inheritance if your pea plants were all shades of "kinda yellowish-greenish-not-quite-roundish." Chaos!

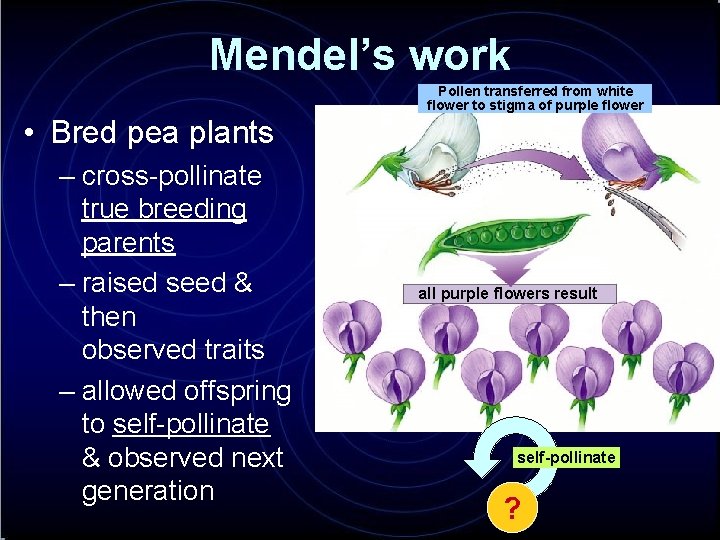

So, what exactly was he doing when he was transferring that pollen? Think of pollen as the male part of the plant's reproductive system. It carries the genetic information – the blueprints, if you will – from the "father" plant. Mendel’s job was to take that pollen and introduce it to the "mother" plant, specifically to its stigma, which is the receptive part of the female reproductive organ. It’s like a very, very slow, very botanical dating app. He’d carefully snip off the stamens (the pollen-producing parts) of the plant he wanted to be the "mother" so it couldn't self-pollinate. This was crucial, because he wanted his chosen cross, his intentional mix, and not some surprise visitor showing up unannounced.

Then, with his tiny brush, he’d collect pollen from the "father" plant. He’d make sure it was good, healthy pollen. No wilted stuff for Mendel. He was all about quality control. And then, with the gentle touch of a surgeon (or maybe a very nervous baker decorating a cake), he'd transfer that pollen to the waiting stigma. It’s a delicate dance, a whispered promise of new life, all happening on a microscopic level. And he did this for thousands of plants. Thousands! My hands would be cramping just thinking about it. My patience would have evaporated faster than dew on a hot day. But Mendel… he just kept going.

Why was this so revolutionary? Before Mendel, people generally believed in something called blending inheritance. The idea was that traits from parents just mixed together like paint. So, if you bred a tall plant with a short plant, you'd get a medium-height plant. Simple, right? And it made a kind of intuitive sense. But Mendel’s experiments showed this wasn’t the whole story. Not even close.

He observed that when he crossed, say, a plant that always produced round peas with a plant that always produced wrinkled peas, the first generation of offspring (he called these the F1 generation) all had round peas. All of them. Not a single wrinkled pea in sight. This was weird. If it was just blending, you’d expect some hint of wrinkle, some imperfection, right? But no, they were all perfectly round. It was like the "wrinkled" trait had just… disappeared. Vanished into thin air. Where did it go?

This is where the genius of Mendel’s approach really shines. He didn't just look at the F1 generation. He let those plants self-pollinate (or he’d cross them with other F1 plants) to create the next generation, the F2 generation. And then, BAM! The missing trait reappeared. In this F2 generation, he found that about a quarter of the peas were wrinkled, and three-quarters were round. Eureka! Or, as Mendel probably muttered to himself, "Ah, yes. Quite so."

This led him to his groundbreaking ideas. He proposed that instead of blending, traits were passed down in discrete units. He called these factors, but we now know them as genes. And for each gene, an organism inherits two copies, one from each parent. So, for pea shape, there’s a gene for roundness and a gene for wrinkledness. Now, here’s the kicker: these genes have different versions, called alleles. So, you can have the allele for round (let’s call it 'R') and the allele for wrinkled (let’s call it 'r').

Here’s where it gets a little mind-bendy, so lean in. If an organism has two copies of the same allele – say, two 'R's (RR) or two 'r's (rr) – it’s called homozygous. It will definitely show that trait. But if it has one of each allele – an 'R' and an 'r' (Rr) – it’s called heterozygous. And in a heterozygous state, one allele can mask the other. The allele that masks the other is called dominant, and the one that gets masked is called recessive. In the case of peas, the allele for roundness (R) is dominant over the allele for wrinkledness (r).

So, when Mendel crossed a pure-breeding round pea plant (RR) with a pure-breeding wrinkled pea plant (rr), all the F1 offspring inherited one 'R' from one parent and one 'r' from the other. They were all Rr. Because 'R' is dominant, they all appeared round. The 'r' allele was still there, lurking in their genetic makeup, but it wasn't expressed. It was like wearing a slightly drab coat over a fabulous, sequined suit – you know the suit is there, but it’s not what everyone sees.

Then, when those Rr plants reproduced, they could pass on either their 'R' allele or their 'r' allele. So, you could get an offspring that inherited 'R' from both parents (RR – round), 'r' from both parents (rr – wrinkled), or 'R' from one and 'r' from the other (Rr – round, because R is dominant). This is why, in the F2 generation, you see that classic 3:1 ratio of dominant to recessive traits. Three out of four appeared round, and one out of four appeared wrinkled. The recessive trait, which had seemed to disappear, had made its triumphant return!

This was a massive shift. It explained how traits could be passed down without just fading into a muddled mess. It showed that we have these distinct units of inheritance, and that some can be more powerful than others. It’s like having secret family recipes. Your grandmother might have a killer cookie recipe, but her neighbor has one for the most amazing pie. If your mom gets both recipes, she might find she’s naturally better at baking cookies (the dominant trait), but she still has the pie recipe in her arsenal, and she can pass that down to you too, even if she doesn't bake pies herself as often.

Mendel's work was so far ahead of its time that, sadly, it was largely ignored during his lifetime. Can you imagine spending years meticulously cross-pollinating plants, carefully recording every single outcome, and then having everyone be like, "Meh"? It’s a bit like spending ages crafting the perfect artisanal cheese only to find out everyone prefers that pre-sliced, plastic-wrapped stuff. The irony is almost unbearable.

It wasn't until decades later, in the early 1900s, that other scientists rediscovered his papers. And when they did, they were astounded. They realized that this humble monk, working in his monastery garden, had laid the very foundations of genetics. He essentially invented the field without even knowing it. He gave us the language to talk about how we inherit things, from the color of our eyes to our predisposition to liking certain foods (though that’s a bit more complex than simple Mendelian inheritance, but you get the idea!).

So, the next time you see a pea pod, or even just a particularly striking flower, take a moment to appreciate the legacy of Gregor Mendel. That simple act of transferring pollen, of carefully orchestrating genetic combinations, unlocked some of the universe’s most fundamental secrets. It's a testament to observation, patience, and the power of asking really, really good questions. And it all started with a monk, some pea plants, and a whole lot of tiny brushes. Who knew such a seemingly simple act could change the world of science forever?