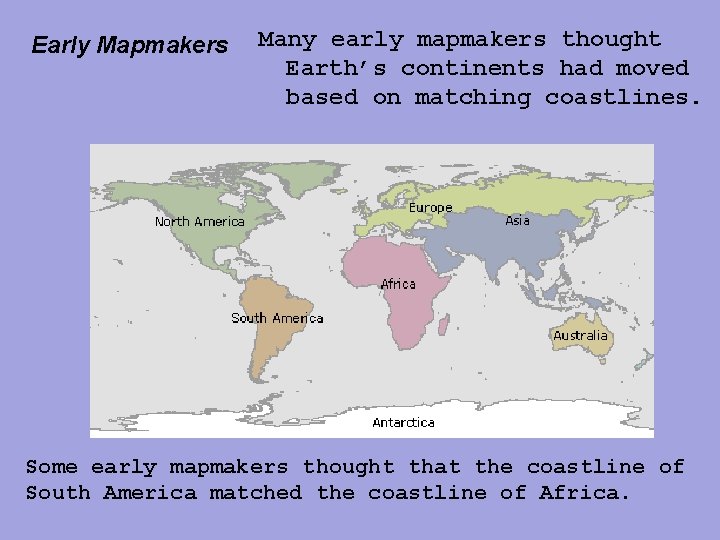

Many Early Mapmakers Thought Earth's Continents Had Moved Based On

Hey there, fellow Earthlings! Ever looked at a map and thought, "Wow, these continents look like they could fit together like puzzle pieces"? Turns out, you're not alone! For a long time, people have been noticing this weird continental jiggle, and it's pretty mind-blowing to think about how early thinkers were already scratching their heads about it.

It's like, imagine you have a bunch of giant Lego bricks scattered around your room. You might start to wonder, "Did these things just randomly land here, or were they put down in a specific order?" That's kind of the feeling early mapmakers and thinkers must have had when they gazed upon the Earth's landmasses.

So, what's the big deal? Well, for centuries, the prevailing idea was that the continents were pretty much fixed. They were just… there. Like mountains or oceans, they were part of the unchanging scenery of our planet. But then, things started to shift. Pun intended, of course!

The "Aha!" Moments

One of the most famous sparks of this idea comes from the 16th century, and it's all thanks to a dude named Abraham Ortelius. He was a cartographer, basically a map-making wizard, and he created these incredibly detailed maps that were super popular. As he was drawing and studying coastlines, he must have had this recurring thought:

"Wait a minute… look at the coast of South America. And then look at the coast of Africa. Doesn't that look like a really good match?"

It's like finding two socks that are almost identical, but one is a little bit stretched out. Ortelius wasn't the first person to notice this, mind you. Ancient Greeks and Romans had their own observations about shorelines. But Ortelius really laid it out there, suggesting in his writings that these landmasses might have been "torn apart by earthquakes and floods."

Think about that for a second. He's not talking about tiny little shifts. He's talking about massive, cataclysmic events that would have ripped continents apart. Pretty dramatic, right? It’s like imagining your living room furniture suddenly rearranging itself overnight without you even noticing the noise.

It's All About the Edges

The real fascination for these early thinkers was the shape of the continents. They weren't just looking at rough outlines. They were seeing these intricate, interlocking edges. It was like looking at the coastline of Brazil and then the coastline of West Africa and realizing they had these complementary curves.

Imagine you’re a detective, and you find a broken piece of a vase. You then find another piece, and as you bring them together, they fit perfectly. That’s the kind of visual evidence these early mapmakers were seeing with the continents. It wasn't just a vague resemblance; it was a remarkably snug fit.

It made them question: what if these continents were once connected? What could have happened to separate them? This was a radical thought in an era where geological time was not well understood, and the Earth was often seen as a more static creation.

Beyond Just the Edges: Other Clues

But it wasn't just about the coastlines fitting together. Other curious observations started to pop up that supported this "moving land" idea.

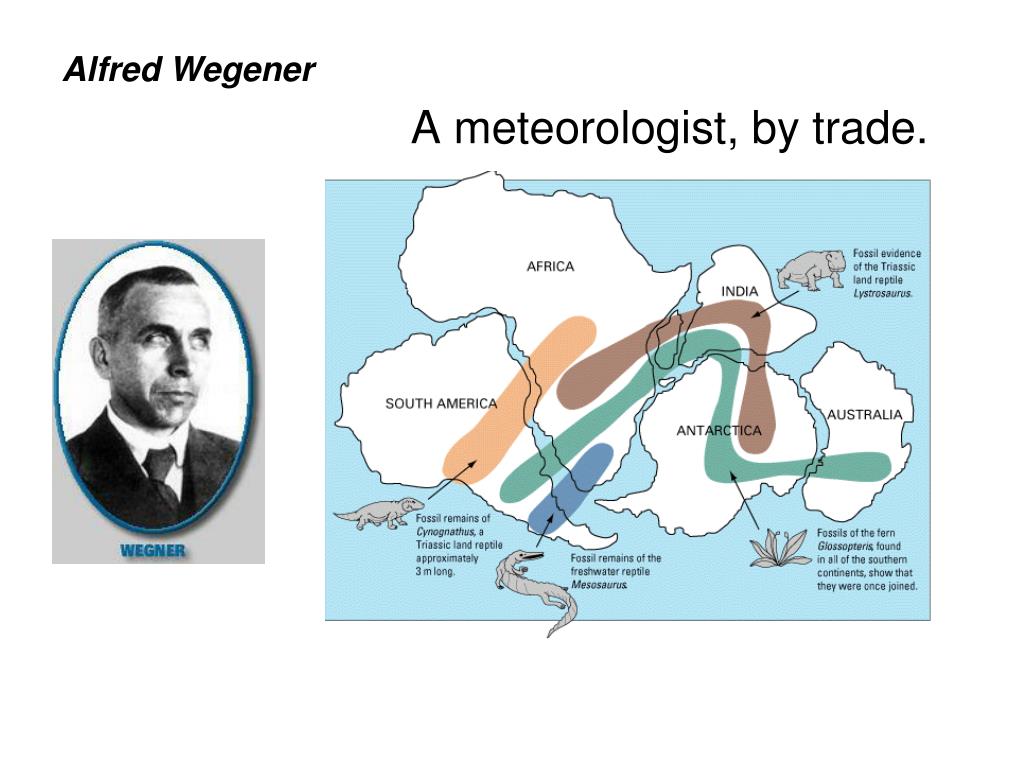

For instance, scientists and explorers started finding the same types of fossils in places that are now separated by vast oceans. Think about finding the same specific dinosaur bone in both India and Madagascar. How could that happen unless those landmasses were once closer, or even joined?

It’s like finding the same rare seashell on beaches on opposite sides of a huge lake. You’d start to think, "Okay, how did that happen? Did someone swim across with it? Or were those beaches once connected?"

This fossil evidence was a huge piece of the puzzle. It pointed towards a shared past, a time when creatures could roam freely across land that is now divided by water. And this wasn't just a few isolated cases. These matching fossils were found in various locations, making the pattern harder to ignore.

Another curious finding was the presence of similar rock formations and geological structures in widely separated regions. Imagine finding identical types of fancy marble used in two different ancient buildings on opposite sides of the world. It would make you wonder if they came from the same quarry, or if perhaps the land where those quarries existed was once closer together.

These geological parallels added more weight to the idea that the Earth's surface wasn't always the way it appeared on their maps. It suggested a dynamic history, a planet that had undergone significant transformations over time.

The "Why" Question Looms Large

Of course, even with all these intriguing clues, the big question remained: how did this happen? Early thinkers didn't have the concept of plate tectonics, which is our modern explanation. They were working with the knowledge and tools of their time, and their ideas were often based on more dramatic, visible events.

Some suggested that the Earth was a shrinking ball, and as it cooled, the surface wrinkled up, creating mountains and pushing continents around. Others imagined continents literally sinking into the ocean, making way for new landmasses to emerge. These were attempts to explain the observable evidence with the theories available.

It’s a bit like trying to fix a complex gadget with only a screwdriver and a hammer. You can make some progress, but you're missing a lot of the specialized tools. These early explanations were their "screwdrivers and hammers" for understanding continental movement.

The Long Road to Acceptance

Even with compelling observations, the idea that continents moved wasn't immediately accepted. For a long time, it was considered a bit of a fringe theory, a curiosity rather than established science. The prevailing scientific view held that continents were permanent features.

Think about it: changing your mind about something you've always believed to be true can be hard. And when that "something" is the very ground beneath your feet, it’s an even bigger leap. It required a whole lot of evidence and a shift in how people understood the planet's deep history.

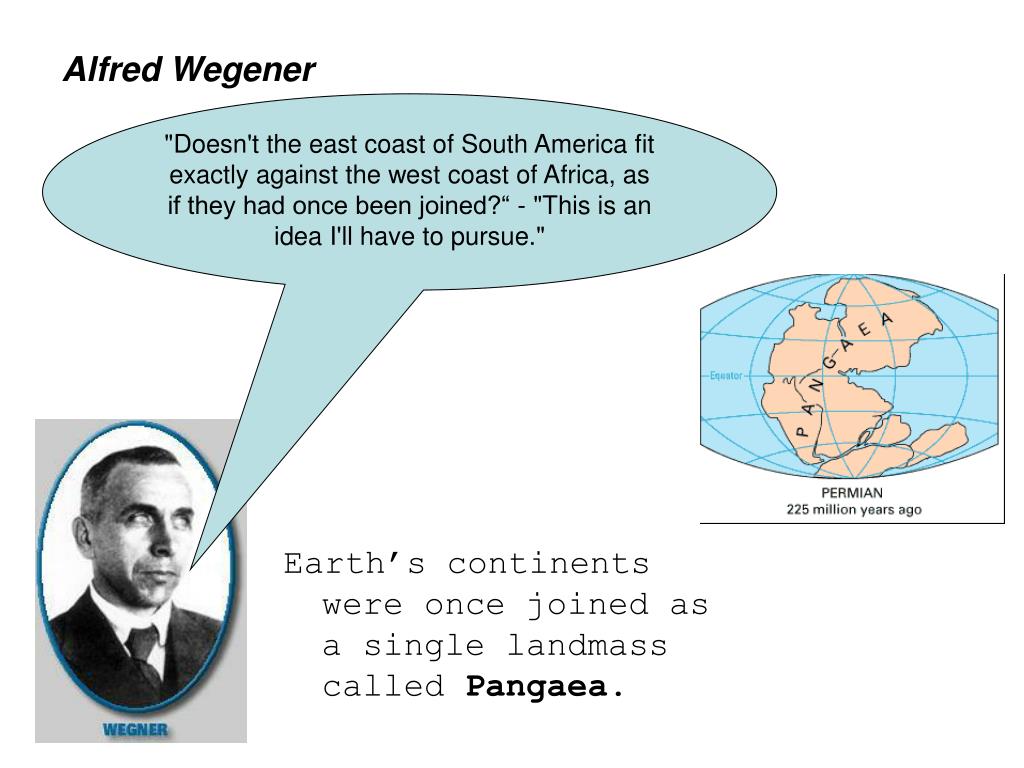

It took the work of many brilliant minds over centuries, with new technologies and more comprehensive data, to finally build the case for what we now call plate tectonics. Alfred Wegener, in the early 20th century, was a major proponent of continental drift, and while he faced a lot of skepticism, his work laid crucial groundwork.

Why It's So Cool Today

So, why is this whole early mapmaking puzzle so fascinating? Because it shows us that human curiosity and the drive to understand our world are ancient. These early mapmakers, armed with their ink, parchment, and keen eyes, were essentially early geologists and geophysicists, noticing patterns that baffled them.

It’s a reminder that scientific progress isn't always a straight line. It’s often a winding path, full of observations, hypotheses, and eventually, a more complete understanding. And sometimes, the most revolutionary ideas start with just looking at a map and saying, "Hey, something's not quite adding up here."

So next time you’re looking at a globe or a map, take a moment to appreciate those early thinkers. They were the ones who first dared to imagine our planet not as a fixed picture, but as a dynamic, ever-changing masterpiece. Pretty neat, huh?