In The Cells Of Some Organisms Mitosis Occurs Without Cytokinesis

Okay, so picture this: you're at a swanky biological party, and everyone's mingling, having a grand old time. The cell is the star of the show, and it's about to do the most mind-blowing dance move ever. We're talking about mitosis, the cell's way of making an exact copy of itself. Think of it as a cellular cloning convention. But sometimes, this party gets a little… weird.

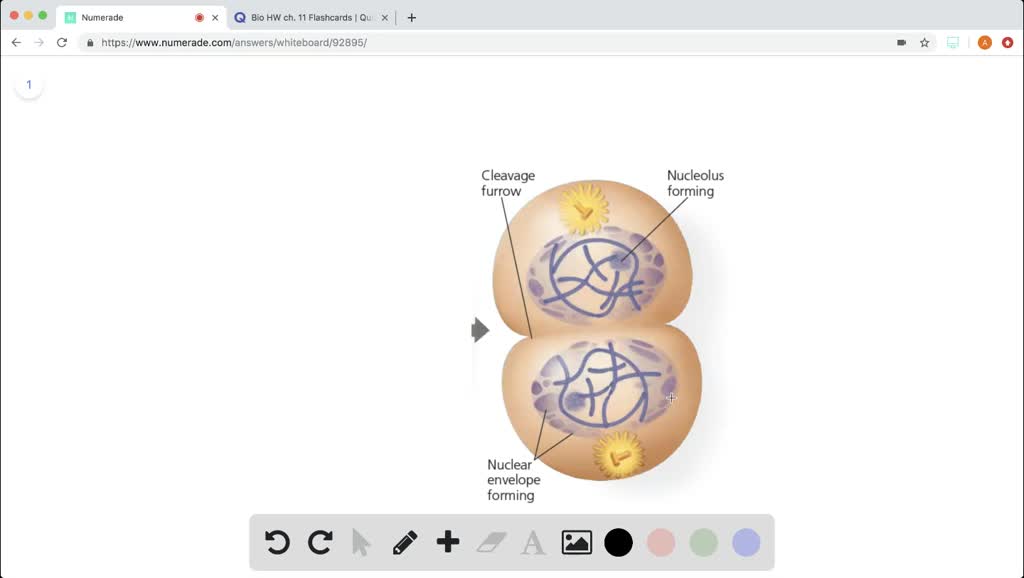

Usually, after the main event – the nuclear division, where all the chromosomes do a synchronized split – the cell throws another party called cytokinesis. This is where the cell literally pinches itself in two, like a tiny, overenthusiastic balloon animal sculptor, creating two perfectly identical daughter cells. It’s the grand finale, the confetti drop, the celebratory "ta-da!" of cell division.

But, and here's where things get hilariously awkward, sometimes, just sometimes, the cell forgets the second part of the act. It's like the DJ plays the last song, the lights come up, but nobody leaves the dance floor. The nucleus divides, boom! Two new sets of chromosomes, ready to party in their own little kingdoms. But the cell itself? It stays one big blob. No pinching. No splitting. Just a cell with two nuclei. Can you imagine the awkward silence?

This phenomenon, my friends, is called mitosis without cytokinesis. It's the biological equivalent of ordering a two-topping pizza and then realizing you only got the dough and the cheese. You've got the components, but the whole experience is just… incomplete. Or, maybe it's like getting a perfectly wrapped present, shaking it, and realizing it’s still one giant package, but inside, there are two distinct gift tags. What do you do with that?

Now, you might be thinking, "That sounds like a biological blooper reel! What kind of organisms are these messy dividers?" Well, prepare to be surprised. This isn't some fringe, experimental stuff. It happens in a whole bunch of places, from the microscopic to the… well, the still pretty microscopic, but important! For instance, think about those tiny but mighty organisms that make up a big chunk of the ocean's plankton – the dinoflagellates. They’re notorious for this. They’re like the rock stars of the microscopic world, dividing their genetic material like it's nobody's business, but sometimes, they get so caught up in the genetic groove that they forget to separate. Oops!

And it’s not just the tiny guys. Some fungi, the unsung heroes (or villains, depending on your perspective) of decomposition and deliciousness, also get in on this multinucleated action. Imagine a mushroom cell that's decided to have a boardroom meeting with itself, but instead of two CEOs, it’s got two whole sets of directors running the show within the same company walls. It's a multitasking marvel or a recipe for internal conflict, depending on your interpretation.

Then there are plants. Oh, the plants! Certain plant tissues, especially during development, can exhibit this. It’s like a plant cell deciding, "You know what? Today, we're going to be a communal living situation for nuclei." Instead of building a new wall to separate the two new nuclear families, they just let them coexist. It's the ultimate in open-plan living, but for chromosomes.

So, why on earth would a cell do this? What's the evolutionary advantage of being a binucleated blob?

Well, sometimes, it's about speed. If an organism needs to reproduce really quickly, like when conditions are just right and they need to seize the moment (think of it as a biological "carpe diem!"), skipping cytokinesis can save precious time. It's like deciding to have a quick buffet lunch instead of a sit-down three-course meal. Get the nutrients in, then worry about the etiquette later.

Other times, it’s about efficiency. Having multiple nuclei within a single cell can sometimes lead to faster or more robust responses to environmental changes. It's like having a super-powered cell with multiple brains, all contributing to decision-making. Imagine one nucleus handling photosynthesis instructions while another is busy coordinating defense mechanisms. It’s a cellular task force!

And let's not forget the sheer coolness factor. Some organisms have evolved to require this state. Certain algae, for example, will happily exist as multinucleated cells for part of their life cycle. They’re not messing up; they’re doing it right for them. It’s like a species of bird that has evolved to have three wings instead of two. It might look odd to us, but it’s perfectly functional for them.

Consider the human body. While most of our cells are busy being perfectly singular and law-abiding, there are whispers, or more accurately, scientific studies, suggesting that even in us, multinucleation can happen under certain circumstances. For instance, during bone healing, cells called osteoclasts can fuse together, creating a massive, multinucleated cell that's excellent at breaking down bone. So, in a way, these messy dividers are part of our own repair crew!

It’s also a fascinating tool for researchers. Scientists can deliberately induce multinucleation in lab settings to study how cells function with multiple nuclei or to create specialized cell lines. It’s like having a special effects department for biology, allowing them to create "monster cells" for observation.

So, the next time you’re admiring a beautifully divided cell under a microscope, remember that there’s a whole other world of cellular shenanigans happening out there. A world where the nucleus divides, but the cytoplasm is too busy to catch up. It's a testament to the bizarre, brilliant, and sometimes downright hilarious ways life finds to keep going, to reproduce, and to simply be. It's a reminder that even in the tiniest corners of the universe, things don't always follow the script. And honestly, isn't that a lot more interesting?

It's a biological party where the guest of honor has duplicated, but the venue hasn't quite figured out how to split yet. And that, my friends, is just another day in the wild, wonderful world of cellular biology.