Identifying The Important Intermolecular Forces In Pure Compounds

Hey there, science curious folks! Ever wonder what makes water… well, water? Or why oil and water are such BFFs that they refuse to mix? It’s not just some mystical magic happening in those molecules. Nope, it’s all about the invisible hugs they give each other – we’re talking about intermolecular forces. Sounds a bit technical, right? But honestly, it’s one of the coolest things about chemistry, and once you get the hang of it, you'll see the world a little differently.

Think of it like this: molecules are tiny little building blocks, and they’re not just floating around solo. They actually interact. They’re attracted to each other, or sometimes they might gently push each other away. These interactions, these “intermolecular forces,” are the real reason why different pure compounds behave the way they do. They dictate everything from whether something is a solid, liquid, or gas at room temperature, to how sticky it is, or even how easily it evaporates. Pretty neat, huh?

So, how do we figure out which of these invisible forces are the important ones in a pure compound? It’s like being a detective, but instead of clues, we’re looking at the structure of the molecules themselves. The shape and the distribution of charges within a molecule are the big giveaways. It’s all about the tiny electrical attractions and repulsions between adjacent molecules.

The Big Three (and a Little Extra!)

When we talk about the "important" intermolecular forces, we're usually focusing on a few main players. They have some fancy names, but let's break them down like we're unpacking a new gadget.

London Dispersion Forces (The "Every Molecule Ever" Hug)

First up, we have London Dispersion Forces, sometimes called van der Waals forces. Now, you might be thinking, "Okay, this is going to be complicated." But here's the really cool part: every single molecule experiences these forces. Yes, you heard that right. Even seemingly simple, neutral molecules have them.

How does this work? Well, electrons in an atom or molecule are constantly buzzing around. At any given instant, the electrons might be a little more on one side than the other, creating a temporary, weak imbalance of charge – a little temporary dipole. This temporary dipole can then nudge the electrons in a neighboring molecule, inducing a similar temporary dipole. And voilà! A weak attraction is born. It’s like two people bumping into each other by accident and then sharing a quick, awkward smile. These forces are generally quite weak, but if you have a lot of molecules, or very large molecules, these little nudges can add up and become significant.

Think about how much different gases there are. Helium, for instance, is super light and its atoms are tiny. The London Dispersion Forces between helium atoms are incredibly weak, which is why helium stays a gas even at very low temperatures. Contrast that with something like iodine, which is a solid at room temperature. Iodine molecules are much larger, with more electrons, leading to stronger London Dispersion Forces that can hold them together in a solid state.

Dipole-Dipole Forces (The "Kind Of Charged" Connection)

Next, we’ve got Dipole-Dipole Forces. These forces are a step up in strength from London Dispersion Forces and happen in molecules that have a permanent dipole. What's a dipole? It's like a molecule having a "positive end" and a "negative end" all the time, not just for a fleeting moment. This happens when atoms in a molecule have different electronegativities (their "pull" on electrons).

Imagine a molecule like hydrogen chloride (HCl). Chlorine is much more electronegative than hydrogen, so it pulls the shared electrons closer to itself. This gives the chlorine end a slightly negative charge (δ-) and the hydrogen end a slightly positive charge (δ+). Now, these molecules are like tiny magnets, with their positive ends attracted to the negative ends of their neighbors. It’s a more stable and stronger attraction than the temporary ones from London Dispersion Forces.

These forces are crucial in substances like acetone (the stuff in nail polish remover). Acetone molecules have a polar carbonyl group (C=O), meaning there’s a permanent dipole there. This allows for significant dipole-dipole interactions, which makes acetone a liquid at room temperature and allows it to dissolve other polar substances.

Hydrogen Bonding (The "Super-Duper" Attraction)

And now, for the rockstar of intermolecular forces: Hydrogen Bonding! This is a special, extra-strong type of dipole-dipole interaction. It’s not a chemical bond in the sense of atoms being chemically joined together, but it's a lot stronger than typical dipole-dipole forces.

Hydrogen bonding occurs when a hydrogen atom is bonded to a highly electronegative atom, specifically oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), or fluorine (F). This creates a very strong partial positive charge (δ+) on the hydrogen. This highly positive hydrogen is then strongly attracted to a lone pair of electrons on a nearby electronegative atom (O, N, or F) of another molecule.

Think of water (H₂O). Oxygen is super electronegative, and it's bonded to two hydrogens. This makes the hydrogens very positive and the oxygen very negative. These water molecules then form a beautiful network of hydrogen bonds with each other. It's like a group of friends holding hands really tightly. This is why water has such a high boiling point for its small size, why ice floats (those hydrogen bonds create an open structure), and why water is such a good solvent for so many things. Without hydrogen bonding, life as we know it would be very different!

Another great example is ammonia (NH₃). The nitrogen atom is highly electronegative, and the hydrogens bonded to it participate in hydrogen bonding. This makes ammonia a liquid at room temperature, even though it’s a gas under normal conditions without these strong attractions.

So, How Do We Know Which is "Important"?

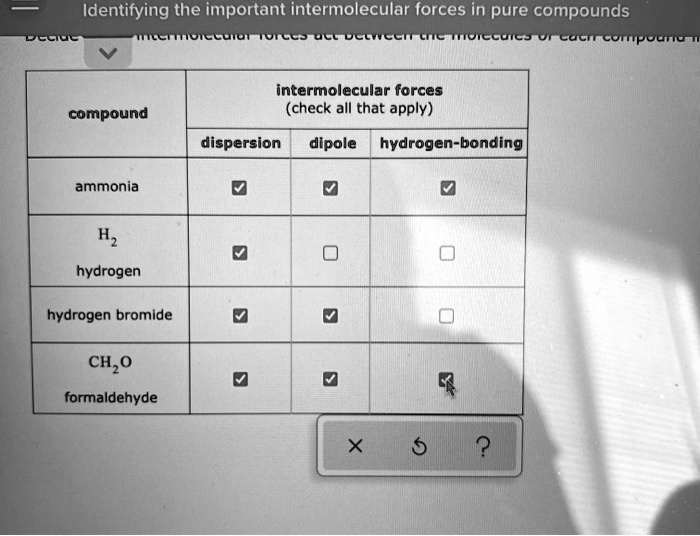

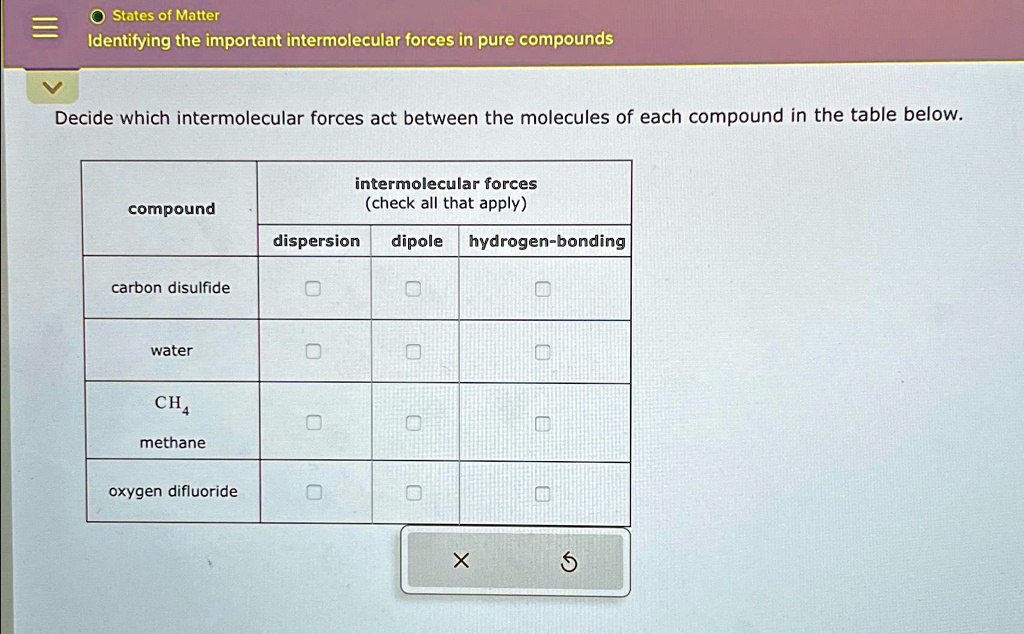

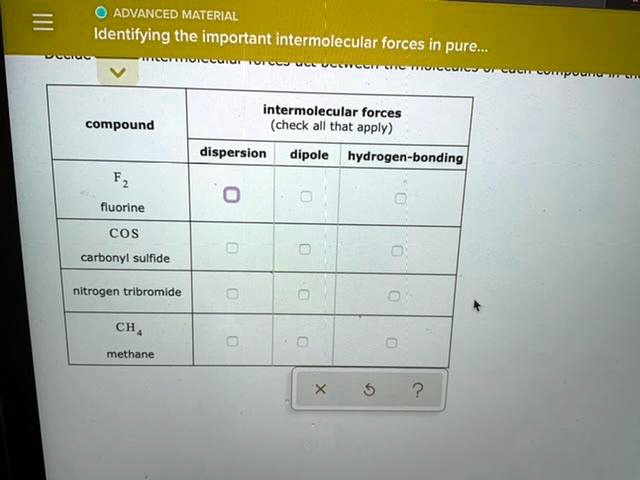

The key to identifying the important intermolecular forces in a pure compound lies in understanding the polarity of its molecules. Is the molecule symmetrical, even if it has polar bonds? If so, the individual bond polarities might cancel out, and the molecule might be nonpolar. In this case, London Dispersion Forces will be the dominant (and often only) intermolecular force.

If the molecule has an uneven distribution of electron density, resulting in permanent positive and negative ends (a dipole), then Dipole-Dipole Forces will be present, in addition to London Dispersion Forces. Remember, London Dispersion Forces are always there!

And if the molecule has hydrogen atoms directly bonded to oxygen, nitrogen, or fluorine, and those electronegative atoms have lone pairs of electrons available, then you're likely to have significant Hydrogen Bonding. This will usually be the strongest force at play.

It’s like a hierarchy. All molecules have London Dispersion. Polar molecules add Dipole-Dipole. Molecules capable of Hydrogen Bonding get that extra, powerful attraction on top. The stronger the intermolecular forces, the more energy it takes to overcome them – and that translates directly to physical properties like boiling point, melting point, and viscosity.

So, next time you’re looking at a substance, whether it’s water, sugar, or even the air you breathe, remember those invisible molecular hugs. They’re not just abstract concepts; they’re the architects of the physical world around us, making everything from a puddle to a cloud behave in its own unique way. It's a subtle dance, but it's happening all the time, and it's pretty darn cool to be able to see it!