How Many Quantum Numbers Are Required To Specify An Orbital

Ever found yourself staring at a particularly intricate latte art design, marveling at how the barista managed to create such a specific, beautiful shape with just milk and espresso? Or maybe you’ve been captivated by the way a skilled gardener sculpts a hedge into a whimsical creature. There’s a certain magic in specificity, in the ability to pinpoint exactly what makes something… that thing. And nowhere is this magic more profound, more mind-bendingly fascinating, than in the quantum world.

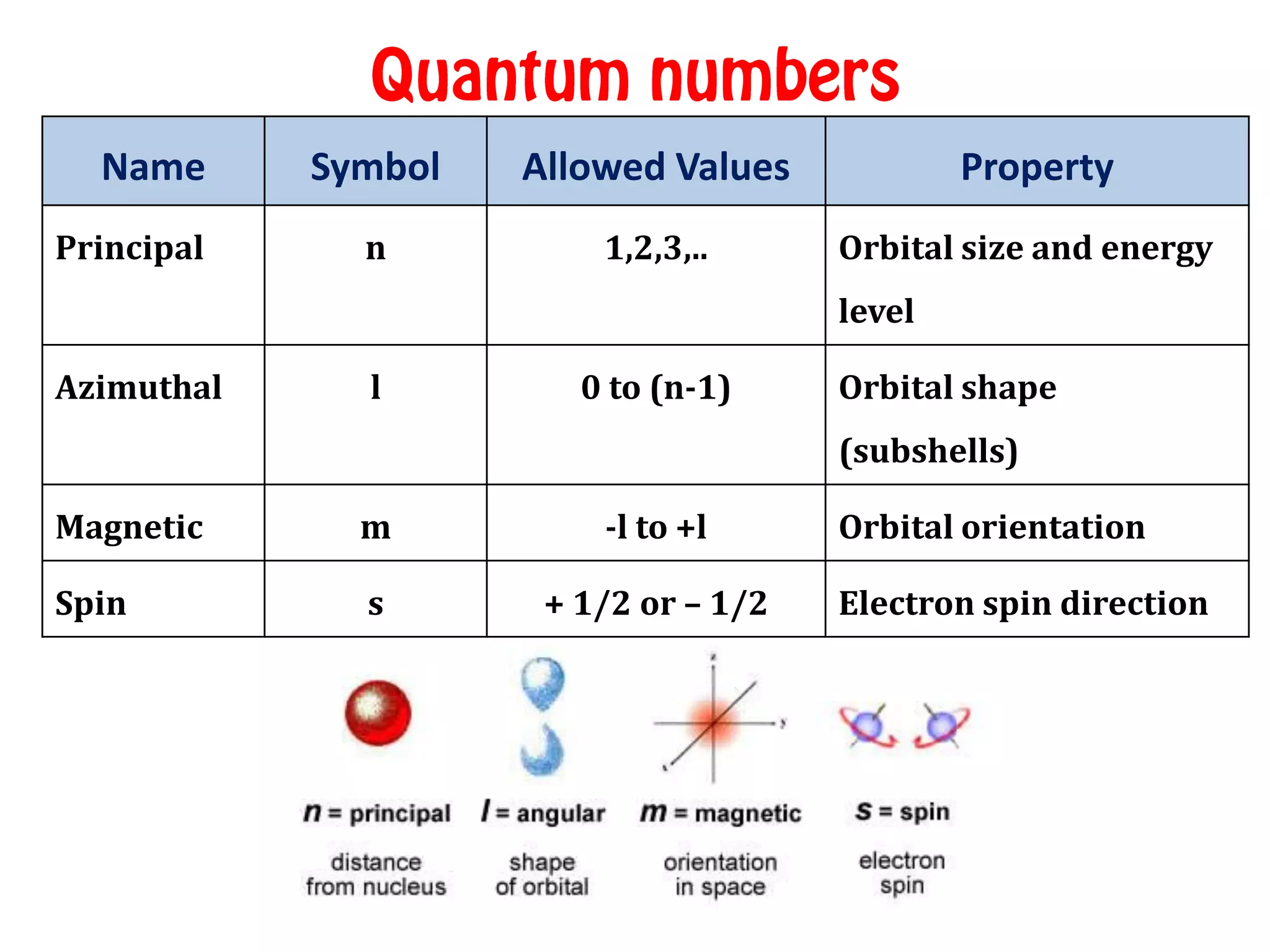

Today, we're diving into a topic that sounds a bit like something out of a sci-fi blockbuster: quantum numbers. But stick with us, because understanding these fundamental descriptors is like unlocking a secret code to the universe’s tiniest building blocks – atoms! Think of it as the ultimate minimalist guide to electron housing. And the big question we’re tackling today is: How many quantum numbers are required to specify an orbital? The answer, my friends, is a neat and tidy three. But oh, the stories those three numbers tell!

The Grand Tour of Electron Neighborhoods

Imagine electrons not as tiny billiard balls zipping around, but more like ethereal clouds of probability. These clouds, the homes where electrons reside within an atom, are called orbitals. They aren't just random spaces; they have specific shapes, sizes, and orientations. And just like you need an address – street name, city, state, and zip code – to find your way to a friend’s place, an electron needs its own set of coordinates to define its orbital. These coordinates are our quantum numbers.

Let’s break down our essential trio, one by one. Think of it as meeting your new neighbors.

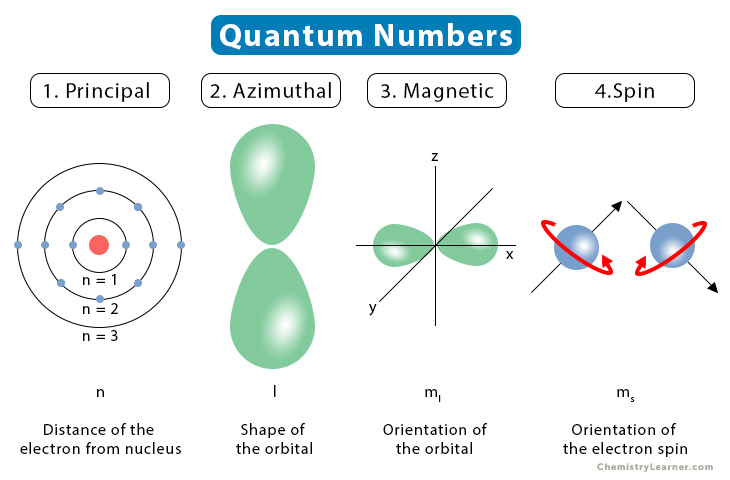

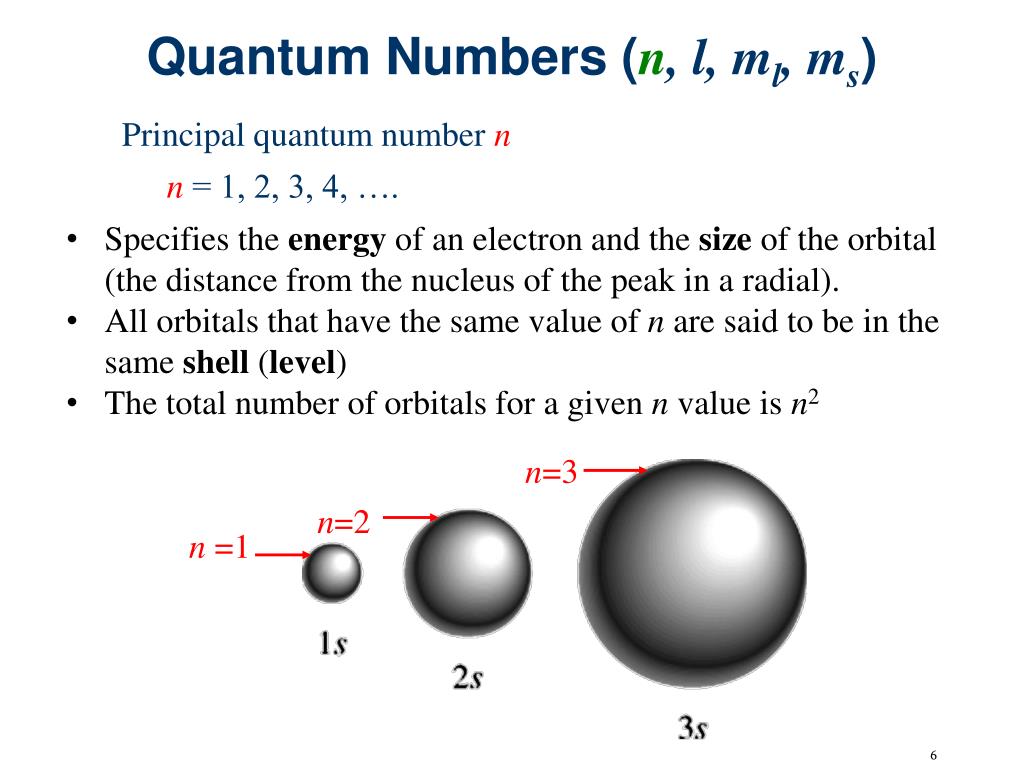

The Principal Quantum Number (n): The Size of the Block

Our first quantum number, the principal quantum number, denoted by a little 'n', tells us about the energy level and the average distance of an electron from the nucleus. It's like the general neighborhood. 'n' can be any positive integer: 1, 2, 3, and so on. The higher the value of 'n', the larger the orbital, the further away the electron is on average from the nucleus, and the higher its energy.

Think of it like selecting a floor in a skyscraper. 'n=1' is the ground floor, cozy and close. 'n=2' is the second floor, a bit bigger and further up. 'n=3' is the penthouse suite, vast and with an incredible view (of the nucleus, that is!). So, if you’re talking about an electron in the first energy shell (n=1), you’re describing a very different space than one in the fifth energy shell (n=5).

Fun Fact: In the early days of quantum mechanics, these energy levels were often visualized as distinct orbits, like planets around the sun. While that model has evolved, the concept of discrete energy levels remains fundamental!

Practical Tip: When you hear about an element being in a particular "period" on the periodic table, you're essentially looking at the principal quantum number of its outermost electrons. For example, elements in Period 3 (like sodium or chlorine) have their valence electrons in the n=3 energy level. It’s a subtle connection that makes the periodic table even more elegant!

The Azimuthal Quantum Number (l): The Shape of the House

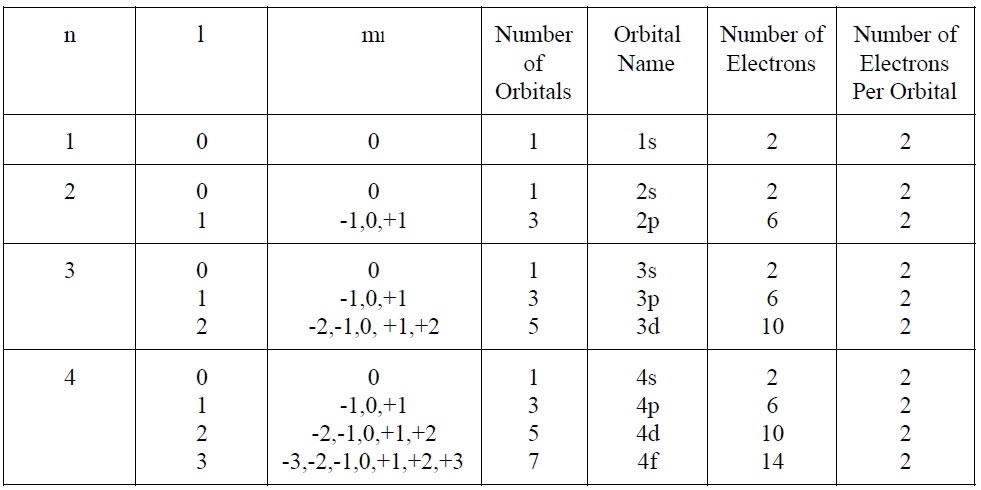

Next up is the azimuthal quantum number, symbolized by 'l'. This little guy is crucial because it defines the shape of the orbital. Unlike the principal quantum number, 'l' has a range of values that depend on 'n'. For a given 'n', 'l' can take on values from 0 up to (n-1).

Now, the numbers themselves aren't the most intuitive labels for shapes, so chemists and physicists have given them letters:

- l = 0 is called an s orbital. These are spherical. Imagine a perfect, perfectly round balloon.

- l = 1 is called a p orbital. These are dumbbell-shaped, with two lobes. Think of a peanut, or those classic cartoon weights.

- l = 2 is called a d orbital. These have more complex shapes, often like cloverleaves.

- l = 3 is called an f orbital. These are even more intricate, with multiple lobes and nodal surfaces.

So, if n=1, the only possible value for l is 0 (since 1-1=0). This means there’s only one type of orbital in the first energy level: a spherical 1s orbital. Simple!

But when we get to n=2, 'l' can be 0 or 1. This gives us both a 2s orbital (spherical) and three 2p orbitals (dumbbell-shaped). This is where things start to get interesting, as different shapes mean different ways electrons can be distributed in space.

Cultural Reference: Think about interior design. The principal quantum number is like deciding to buy a house. The azimuthal quantum number is like choosing the style of the house – modern, Victorian, minimalist? Each style has a different aesthetic and function, just like s, p, d, and f orbitals have different shapes and spatial distributions.

Fun Fact: The labels s, p, d, and f originally came from spectral lines observed from elements. 's' for sharp, 'p' for principal, 'd' for diffuse, and 'f' for fundamental. Pretty neat how observations from the past laid the groundwork for our current understanding!

The Magnetic Quantum Number (ml): The Orientation in Space

We've got the size and the shape. Now, what about the orientation? Enter the magnetic quantum number, represented by 'ml'. This number tells us the orbital’s orientation in three-dimensional space. For a given value of 'l', 'ml' can take on integer values from -l to +l, including 0.

Let's connect this to our shapes:

- For an s orbital (l=0), the only possible value for ml is 0. This makes sense, as a sphere has no preferred orientation in space. It looks the same from every angle.

- For a p orbital (l=1), ml can be -1, 0, or +1. This corresponds to the three dumbbell-shaped p orbitals. They are oriented along the x, y, and z axes of a coordinate system. So, you have a px orbital, a py orbital, and a pz orbital.

- For a d orbital (l=2), ml can be -2, -1, 0, +1, or +2. This gives us five distinct d orbitals, each with a specific spatial orientation.

So, if you're talking about the 2p orbitals (n=2, l=1), you have three distinct orbitals because ml can be -1, 0, and +1. Each of these three orbitals has the same shape (dumbbell) and the same energy (in the absence of external magnetic fields), but they are oriented differently in space.

Practical Tip: When discussing chemical bonding, particularly in organic chemistry, the orientation of orbitals is paramount. The way p orbitals overlap along different axes dictates the geometry of molecules and the types of bonds formed (like sigma and pi bonds). It’s why a carbon atom can form such a variety of complex structures!

Fun Fact: The 'magnetic' in magnetic quantum number comes from the historical observation that in the presence of a magnetic field, spectral lines would split into multiple lines. This splitting was explained by the different spatial orientations of the orbitals interacting with the magnetic field.

Putting It All Together: The Atomic Address

So, to pinpoint a specific orbital, we need to know the values of n, l, and ml. These three numbers, working in harmony, give us the complete "address" of an electron's probabilistic home within an atom.

Let's take an example. An orbital described by n=2, l=1, and ml=0 is the "2pz" orbital. It's in the second energy shell (n=2), it's a p-shaped orbital (l=1), and it's oriented along the z-axis (ml=0).

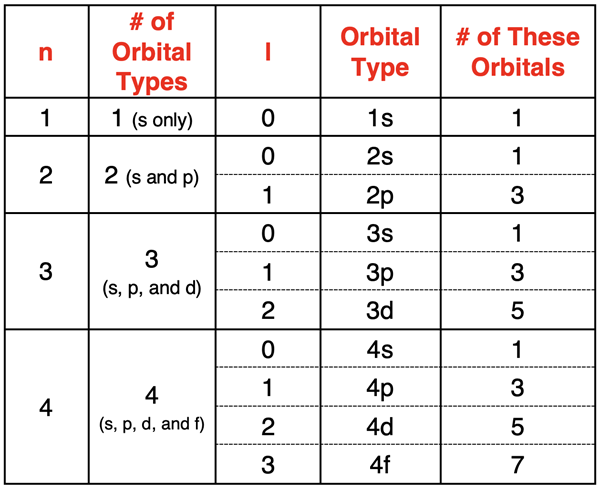

Here's a little table to summarize how many orbitals of each type exist:

- n=1: l=0 (1s orbital). Total: 1 orbital.

- n=2: l=0 (2s orbital) and l=1 (three 2p orbitals: 2px, 2py, 2pz). Total: 1 + 3 = 4 orbitals.

- n=3: l=0 (3s orbital), l=1 (three 3p orbitals), and l=2 (five 3d orbitals). Total: 1 + 3 + 5 = 9 orbitals.

You might notice a pattern here: the total number of orbitals in a given energy level 'n' is n2. How cool is that? It's a simple mathematical relationship that emerges from the quantum rules.

The Unseen Fourth: The Spin Quantum Number

Now, here's a little twist. While three quantum numbers (n, l, ml) are needed to specify the orbital itself – its energy, shape, and spatial orientation – an electron in that orbital also has an intrinsic property called spin. This is described by the fourth quantum number, the spin quantum number (ms).

Electrons behave as if they are spinning, creating a tiny magnetic field. This spin can be in one of two directions, often referred to as "spin up" (ms = +1/2) and "spin down" (ms = -1/2). This is where the famous Pauli Exclusion Principle comes in. It states that no two electrons in an atom can have the same set of all four quantum numbers. So, in any given orbital (defined by n, l, and ml), you can have a maximum of two electrons, and they must have opposite spins.

Think of it like assigning seats in a theater. The orbital (n, l, ml) is the specific row and seat number. The spin quantum number (ms) is whether you’re sitting facing forward or backward in that seat (though for electrons, it’s more like spinning clockwise or counter-clockwise). You can only have two people in that seat, and they have to be facing opposite directions.

Fun Fact: The concept of electron spin was a theoretical prediction that was later experimentally confirmed. It’s a beautiful example of how abstract mathematical ideas can lead to profound physical discoveries!

Beyond the Numbers: A Microscopic Symphony

So, to recap, three quantum numbers (n, l, ml) are essential to specify an orbital. The fourth quantum number (ms) is needed to distinguish between the two electrons that can occupy that orbital. It’s a surprisingly elegant system that governs the behavior of atoms and molecules, and ultimately, the very fabric of our material world.

It’s like having a grand orchestra. The principal quantum number (n) sets the general section (strings, brass, percussion). The azimuthal quantum number (l) defines the instrument within that section (violin, trumpet, drum). The magnetic quantum number (ml) specifies the individual player’s position on stage. And the spin quantum number (ms) is like the unique way each musician plays their instrument, adding individual flair. Together, they create a complex, harmonious symphony.

From the humble hydrogen atom with its single electron in a 1s orbital to the intricate electron configurations of heavy elements, these quantum numbers are the invisible architects. They dictate everything from the color of fireworks (specific electron transitions) to the strength of the bonds in the water you drink.

A Reflection: Finding Your Own "Orbital"

It’s easy to get lost in the abstractness of quantum mechanics, to feel like these concepts are too far removed from our everyday lives. But isn’t there something relatable in the idea of needing specific parameters to define something unique?

Think about your own passions or hobbies. To truly excel at playing the guitar, you need to understand the nuances of fretwork (n), the different types of chords and scales (l), and the specific strumming patterns and finger placements (ml). Even within those, your personal "feel" or interpretation adds that unique touch, that "spin."

Or consider learning a new language. You start with basic vocabulary and grammar (n), then move to sentence structure and idiomatic expressions (l), and finally to pronunciation and conversational fluency (ml). Your individual voice, your cultural background, adds that final layer of uniqueness (ms).

The universe, at its most fundamental level, is about specificity and order, a beautiful dance of probability and precision. And while we may not need to calculate quantum numbers for our morning commute, understanding that such fundamental rules govern existence can offer a subtle sense of wonder. It reminds us that even in the seemingly chaotic, there’s an underlying structure, a set of rules that, when understood, reveal an astonishing depth and beauty. So, the next time you look at a complex pattern, whether it's a quantum orbital diagram or a beautifully crafted mosaic, take a moment to appreciate the numbers, the rules, and the elegant specificity that brought it into being.