How Does A Corpse Decompose In A Coffin

Ever found yourself staring at the ceiling, perhaps after a particularly dramatic episode of a true crime series, and a peculiar question pops into your head? You know, one of those unusual ones that seem to emerge from the quiet corners of our minds? Today, we're diving into a topic that’s often shied away from, but is as natural as a sunrise: what exactly happens to a person when they’re tucked away in a coffin? It’s not a morbid curiosity, really, more like an exploration of nature’s grand, albeit slightly eerie, recycling program. Think of it as a fascinating, albeit slow-motion, documentary playing out beneath the earth.

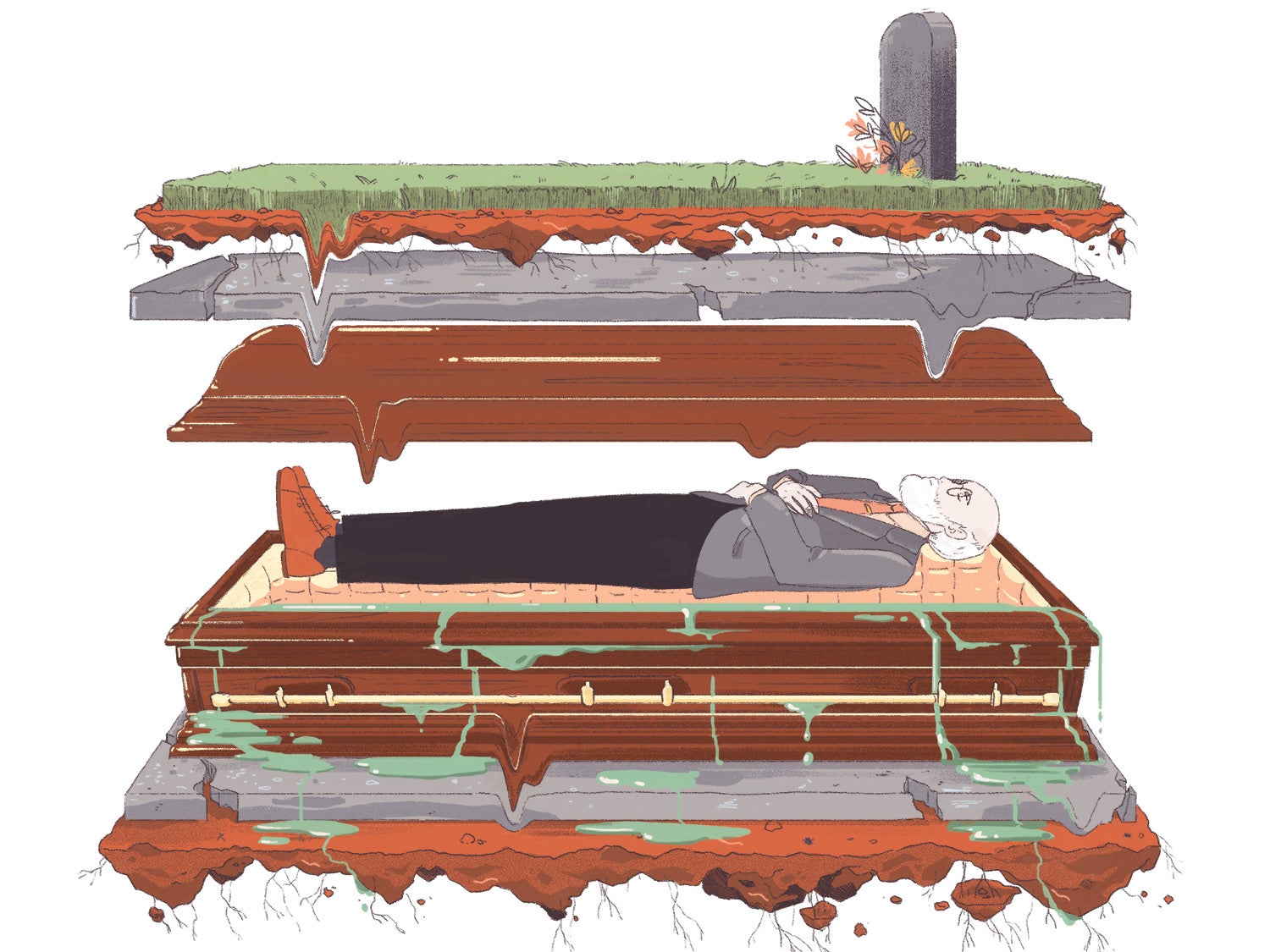

So, let's set the scene. Our dearly departed is resting peacefully in their chosen vessel, a coffin. This isn't just any box, mind you. Traditionally, coffins are made of wood – oak, pine, sometimes more elaborate options for those who fancy a bit of flair even in their final resting place. The idea is that it’s a protective shell, a final sanctuary. But nature, as it always does, has its own plans, and they don't always align with keeping things perfectly preserved.

The Unseen Workforce: Microbes to the Rescue (Sort Of)

The moment life exits the body, a remarkable transformation begins. It’s not a sudden explosion of decay, but a gradual, intricate process driven by an army of microscopic helpers: bacteria and other microorganisms. These tiny organisms, present both inside and outside our bodies, are the true protagonists of decomposition. They’re the unsung heroes of nutrient cycling, and frankly, they’re incredibly efficient at their job.

Initially, the body’s own digestive system, which is packed with bacteria, starts the breakdown process from within. Think of it as the internal cleanup crew getting to work. These bacteria, no longer kept in check by a living immune system, begin to feast on the cells and tissues. This is why, soon after death, you might notice some bloating – it’s the gases produced by these microbial activities.

Outside the body, the environment also plays a role. If the coffin is sealed airtight, the decomposition might proceed a little differently, often leading to a process called anaerobic decomposition, which occurs in the absence of oxygen. If there are small openings or the coffin is more porous, aerobic decomposition, with oxygen present, might occur, often at a slightly faster pace. The moisture content of the soil and the ambient temperature are also huge influencers. It’s a bit like a slow-cooker, where temperature and moisture dictate how quickly things get tender… er, broken down.

The Stages of a Very Slow Fade-Out

While the timeline can vary wildly depending on environmental factors, decomposition generally progresses through several distinct stages. It’s like a natural, albeit somber, lifecycle playing out.

1. Algor Mortis (The Cooling Down): Immediately after death, the body starts to cool down to match the surrounding temperature. This is the first noticeable change, a physical sign that the body’s internal furnace has been extinguished. It’s a gentle return to the ambient temperature of the room or the grave.

2. Rigor Mortis (The Stiffening Up): This is perhaps the most well-known stage. A few hours after death, the muscles in the body stiffen. Think of it as a temporary, involuntary post-mortem yoga session. This stiffness typically lasts for about 24 to 48 hours before gradually dissipating as the muscles begin to break down. It’s a fascinating, albeit temporary, state of rigidity.

3. Livor Mortis (The Pooling of Blood): As circulation stops, gravity takes over. Blood settles in the lowest parts of the body, causing a purplish-red discoloration. This is particularly noticeable on the back if the person is lying on their back. It's a visible manifestation of gravity’s ongoing influence, even after life has departed.

4. Bloating and Active Decay (The Microbial Party): This is where the real microbial action kicks in. As mentioned, bacteria begin to break down tissues, producing gases. This leads to swelling and distention of the body. The skin might start to discolor, and a distinct odor might become noticeable. This is when the truly transformative part of decomposition begins, often accompanied by the appearance of insects, if they can access the body, acting as nature’s tiny scavengers.

5. Advanced Decay (Breaking It Down): In this stage, the soft tissues are largely liquefied and broken down. The body cavity may collapse, and what remains are primarily bones, cartilage, and tougher tissues like skin and hair. The initial breakdown is complete, and the process of returning to basic elements continues.

6. Skeletal Remains (The Final Form): Eventually, all the soft tissues will decompose, leaving behind the skeleton. Even bones, over a very long period and under the right conditions, will eventually break down and return to the earth. It’s the ultimate statement of nature’s complete cycle of renewal.

The Coffin’s Role: Barrier or Accelerator?

Now, you might be thinking, “But what about the coffin? Doesn’t it keep everything in place?” Well, yes and no. A sealed, non-porous coffin can slow down decomposition by limiting the entry of oxygen and moisture, and also by keeping potential scavengers out. However, it doesn't stop the internal processes driven by the body's own microbes. In some cases, a tightly sealed coffin can even lead to a more potent buildup of gases and liquids, a phenomenon sometimes referred to as "liquefaction."

Traditional wooden coffins, on the other hand, are generally more porous and will eventually allow moisture and air to enter, facilitating a more "natural" decomposition process. This is why in some cultures, the focus is on natural materials that will break down along with the body, aiding in its return to the earth. Think of wicker coffins or those made from sustainable woods; they're designed with this natural cycle in mind.

Cultural Touches: From Embalming to Green Burials

Our relationship with death and decomposition is, of course, deeply intertwined with culture and tradition. In many Western societies, embalming has been a common practice. This process involves replacing bodily fluids with a preservative solution, significantly slowing down decomposition. It allows for open-casket funerals and viewing the deceased looking much as they did in life. It’s a way of offering comfort and a sense of closure through preservation.

However, there's a growing movement towards green burials, which embrace natural decomposition. These methods often involve biodegradable shrouds or simple wooden coffins, placed directly in the earth without embalming. The goal is to minimize environmental impact and to facilitate a more direct return to nature. It’s a fascinating shift, reflecting a desire to be more in sync with the earth’s natural rhythms.

Interestingly, historical practices varied greatly. Ancient Egyptians, of course, are famous for their elaborate mummification, a highly advanced form of preservation. In contrast, many ancient cultures practiced simple internment, allowing nature to take its course with minimal interference. It’s a reminder that our current practices are just one chapter in a very long human history of dealing with mortality.

Fun Facts You Might Not Have Known

Did you know that insects play a crucial role in decomposition? Flies are often among the first to arrive, laying eggs that hatch into maggots, which are voracious eaters of decaying flesh. This is why forensic entomologists can use the types and life stages of insects found on a body to estimate time of death! It’s like a tiny, morbid detective agency at work.

And what about those bones? While they seem incredibly durable, even bones will eventually decompose. The rate depends heavily on the soil conditions, moisture, and pH levels. In very dry, alkaline conditions, bones can be preserved for an exceptionally long time, while in acidic or very moist environments, they can break down much faster. It’s a testament to the varied power of the earth.

The smell of decomposition, often described as pungent or sweet and sickly, is due to a mix of compounds, including putrescine and cadaverine. These are produced as proteins break down. While unpleasant to us, they’re a signal to nature's cleanup crew – a rather potent invitation to feast!

Consider the concept of adipocere, also known as corpse wax. In very wet, anaerobic conditions, body fats can transform into a soap-like substance. It's a preservation process that can keep a body recognizable for a surprisingly long time, almost like a natural, albeit unsettling, wax figure.

A Gentle Reminder of Life’s Cycle

Thinking about decomposition, while perhaps not a topic for casual dinner conversation, ultimately brings us back to a fundamental truth: we are all part of a grand, ongoing cycle. Our existence, however long or short, contributes to the vibrant tapestry of life on Earth. The nutrients released from our bodies, after our time here is done, go on to nourish new life, from the smallest microbes to the grandest trees.

It’s a humbling and, in its own way, beautiful thought. It reminds us that life and death are not opposing forces, but rather two sides of the same coin. And in that gentle, inevitable process of returning to the earth, there's a quiet dignity and a profound connection to the world around us. So, the next time you find yourself pondering life’s mysteries, perhaps you can appreciate the extraordinary, unsung work happening beneath the surface, a testament to nature’s eternal renewal. It’s a gentle nudge to live fully, appreciate the present, and perhaps, leave a positive trace behind, however small.