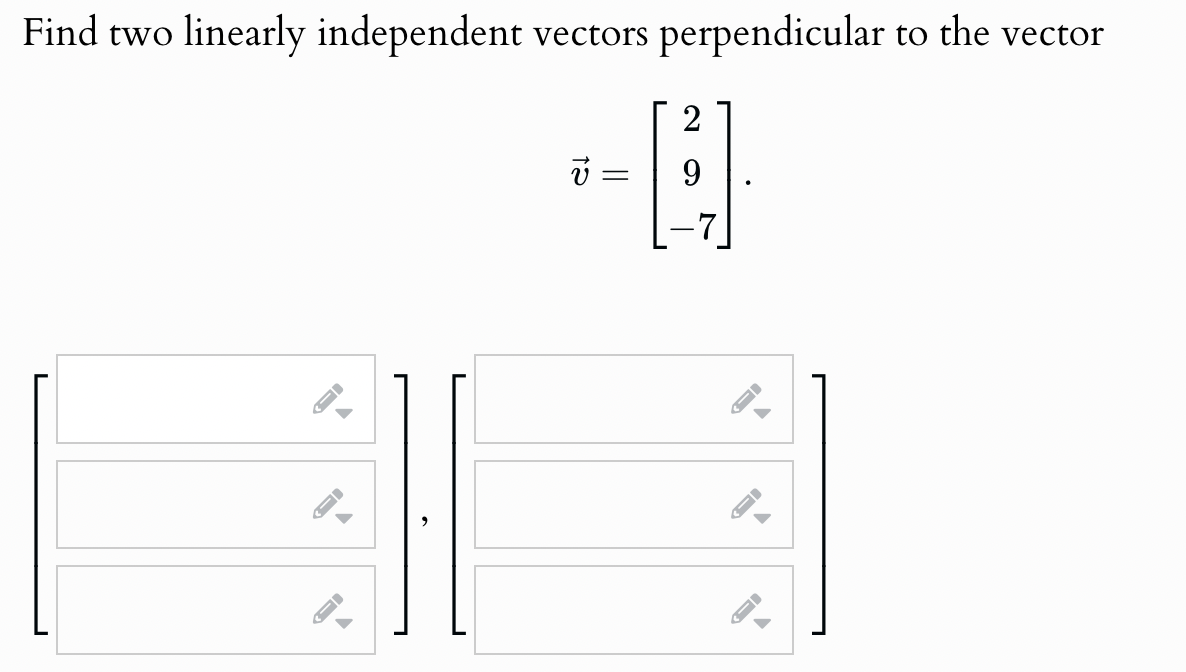

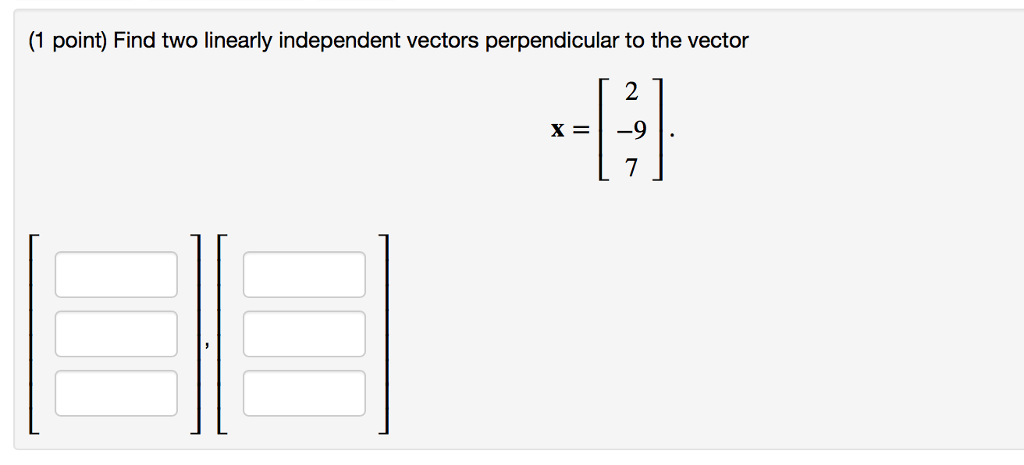

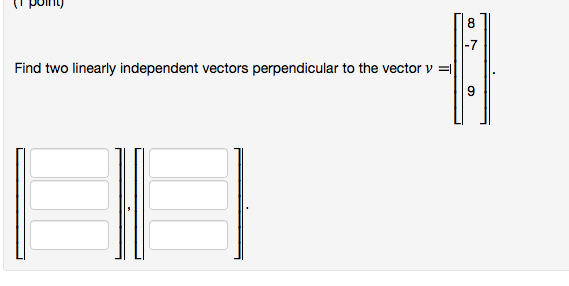

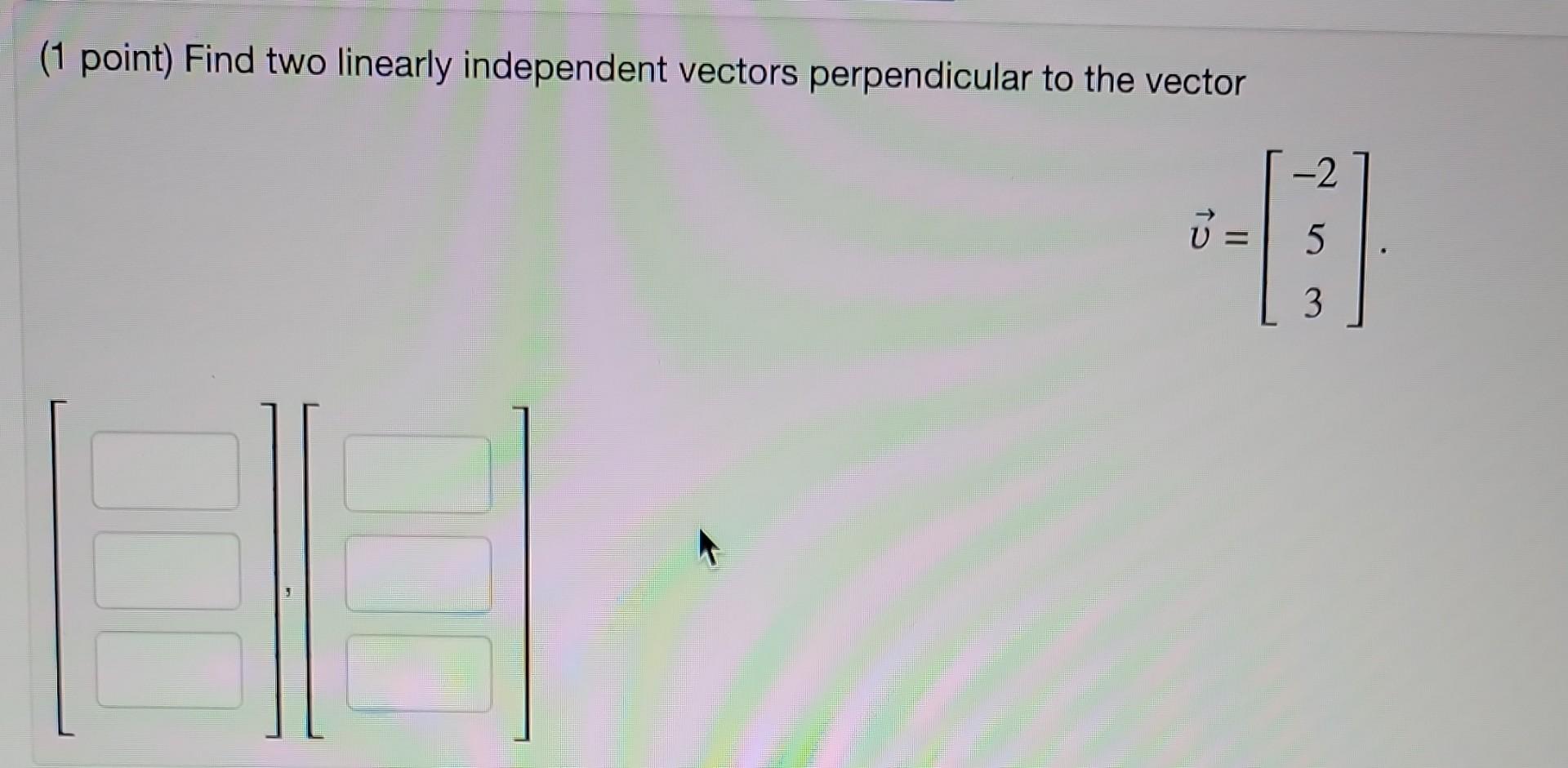

Find Two Linearly Independent Vectors Perpendicular To The Vector

Okay, picture this. You've got a vector. Just one. It's like that one friend who's always the center of attention at a party. Let's call this guy Vector A. He's got direction, he's got magnitude, he's living his best vector life. And you're standing there, maybe with a slightly bewildered expression, thinking, "So, what now?"

Well, my friends, get ready for a little mathematical secret I'm about to spill. It’s not exactly common knowledge, not something your grandma would casually drop over tea. But it's true. You can actually find two other vectors that are totally chilling, completely perpendicular to our pal Vector A. And not just any old perpendicular vectors. Oh no. These are linearly independent ones. Fancy words, I know, but basically, they're not copies or twins of each other. They're their own unique snowflakes in the vector world.

Think of Vector A as a really enthusiastic chef pointing directly at a specific ingredient on a massive buffet. Everyone else is looking where he's pointing. Now, we want to find two people on that buffet line who are facing completely the opposite direction of the chef, but also facing in directions that are different from each other. They're not even looking at the same side of the buffet. They're in their own little perpendicular worlds.

This might sound like a superpower, right? Finding vectors that are best buds with perpendicularity and individuality. It's like having a secret handshake for the geometric elite. We’re not trying to be difficult, we're just trying to understand the neighborhood our vector lives in. We want to map out the cool spots that are not where Vector A is pointing. It's like saying, "Alright, Vector A, you do your thing. We're going to go over here and do our own thing, and we're going to make sure we're not even remotely in your line of sight."

Now, the actual "how" of it is where things get a little… hands-on. It’s not like you can just look at Vector A and poof two perpendicular buddies magically appear. You actually have to do some calculations. It involves a bit of tinkering, a dash of cleverness, and maybe a small sacrifice to the math gods (just kidding… mostly).

Let's say Vector A is represented by some numbers. For example, if we're talking about 3D space, Vector A might look something like (x, y, z). Our mission, should we choose to accept it, is to find two vectors, let's call them Vector B and Vector C, such that Vector B is perpendicular to Vector A, and Vector C is also perpendicular to Vector A. And, crucially, Vector B and Vector C themselves are not pointing in the same direction or the exact opposite direction. They’re doing their own thing, independently.

It’s a bit like being a detective. You've got your prime suspect, Vector A, and you're looking for accomplices who are operating on completely different wavelengths, but also in a way that’s at a right angle to your suspect's operations. You're trying to find the guys who are totally out of sync with the main act, but still… in the same play, so to speak.

One common trick? If Vector A is (x, y, z), and let's assume not all of x, y, or z are zero (otherwise, things get a bit dull), you can often find a simple perpendicular vector by just swapping two of the components and negating one of them. For instance, if Vector A is (1, 2, 3), a potential perpendicular buddy could be (-2, 1, 0). See what I did there? Swapped the first two, negated the first one. Easy peasy, right? Well, sometimes it’s that easy, and sometimes it requires a little more… finesse.

But here’s the real kicker, the thing that makes me think this is an underappreciated art form. You don't just find one perpendicular vector. You find two. And they have to be linearly independent. This is where it gets really fun. It’s like saying, "Okay, Vector A, you’re the leader of the band. We’re going to find two soloists who can play completely different tunes, but neither of them is even thinking about playing your tune."

It's a subtle power, really. It's the power of having options. It's the power of knowing that even when something is pointing in a very specific direction, there's a whole universe of other directions that are completely orthogonal to it, and within that universe, there's plenty of room for independent thought and action. It’s the mathematical equivalent of finding a quiet corner in a noisy room, but then finding another quiet corner that’s miles away from the first one, and neither corner is near the noisy person.

So next time you’re pondering a vector, remember Vector A. Remember that it's not alone in its directional destiny. There are always, always, at least two distinct, perpendicular paths it can’t even imagine going down. And that, my friends, is a little bit of everyday magic.