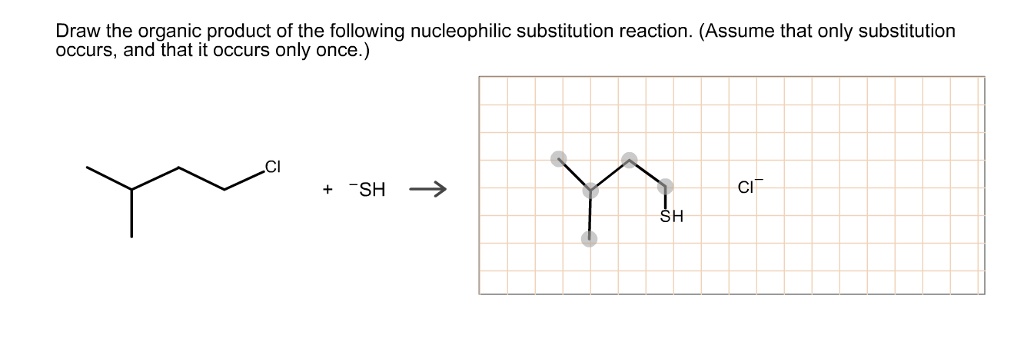

Draw The Organic Product Of The Nucleophilic Substitution Reaction

Hey there, aspiring chemists and curious minds! Ever looked at a chemical reaction and felt like you were trying to decode ancient hieroglyphics? Yeah, me too! But fear not, because today we’re diving into the wonderful world of nucleophilic substitution reactions. Think of it as a molecular dance where one player elegantly steps out, and another swoops in to take its place. Easy peasy, right?

So, what exactly is this "nucleophilic substitution" shindig? Let's break it down. We've got our nucleophile, which is basically a chemical species that's super attracted to positively charged things. They're like the life of the party, always looking for a positive vibe to hang out with. Nucleophiles are usually rich in electrons, which is why they're so eager to share the love (or, you know, the electrons).

And then we have our substrate. This is the molecule where the action is happening. It's got a part that's a bit… well, let's call it "electrophilic." This electrophilic bit is usually connected to something called a leaving group. Think of the leaving group as that awkward friend who’s always ready to bail from a party as soon as things get a little too interesting. They’re just waiting for their cue to exit stage left.

The nucleophilic substitution reaction is all about the nucleophile saying, "Hey there, electrophilic buddy! I see you've got a leaving group hanging around. Mind if I, uh, take over?" And poof, the leaving group departs, and the nucleophile happily settles in. It's like musical chairs, but with molecules and a whole lot less drama (usually!).

The Two Main Acts: SN1 and SN2

Now, like any good performance, there are different ways this molecular dance can play out. The two most common acts are called SN1 and SN2. Don't let the letters and numbers intimidate you; they just tell us how the reaction unfolds.

Let's start with SN2. The "2" here stands for "bimolecular," meaning that in the rate-determining step (the slowest step that controls how fast the whole reaction goes), two molecules are involved. It's a one-step tango! The nucleophile swoops in from the back of the substrate, directly opposite to the leaving group. As the nucleophile forms a bond, the leaving group simultaneously breaks its bond. It’s a coordinated effort, a perfectly synchronized move!

Imagine you’re a chef, and you’re trying to swap out one ingredient for another in a dish. With SN2, you’d be adding the new ingredient and removing the old one at the exact same time. No pauses, no waiting for the old ingredient to fully leave. It’s efficient, like a well-oiled kitchen!

This "backside attack" in SN2 reactions is super important because it often leads to an inversion of configuration. What does that mean? Well, if your substrate has a specific 3D arrangement (think of it like a little pyramid of atoms), the SN2 reaction will flip it upside down, like turning a glove inside out. It’s a neat little trick that tells us a lot about the mechanism!

For SN2 reactions to happen most effectively, we want our substrate to be as unhindered as possible. Think of a little primary alcohol or a methyl halide. These are like spacious dance floors where the nucleophile can easily waltz in without bumping into any bulky substituents. Tertiary substrates, on the other hand, are like crowded dance floors with bouncers – they make it really hard for the nucleophile to get in. So, less branching, more SN2 action!

We also need to consider the solvent. SN2 reactions generally prefer polar aprotic solvents. These are solvents that can dissolve our polar reactants but don't have any acidic hydrogens to interfere with our electron-rich nucleophile. Think of solvents like acetone, DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide), or DMF (dimethylformamide). They create a cozy environment for the nucleophile to do its thing without getting bogged down.

Now, let's talk about SN1.

The "1" in SN1 stands for "unimolecular." This means that in the rate-determining step, only one molecule is involved. This act has two steps, and it's a bit more of a slow-burn romance. First, the leaving group gracefully exits the substrate all by itself. This leaves behind a positively charged species called a carbocation. Think of the carbocation as a lonely heart, looking for some company.

This carbocation formation is the slow step, the bottleneck of the reaction. Once the carbocation is formed, it’s highly reactive and quickly attacked by the nucleophile in a second, fast step. It's like the leaving group took its sweet time to leave, and then bam, the nucleophile jumps in as soon as there's an opening!

Unlike SN2, where the nucleophile has to attack from the back, with SN1, the nucleophile can attack the carbocation from either side. This is because the carbocation is planar, meaning it's flat. So, the nucleophile can approach from the top or the bottom. This often leads to a racemic mixture, where you get a 50/50 mix of both possible stereoisomers (the original configuration and its mirror image). It’s like getting a surprise package with two different but equally valid options!

SN1 reactions are favored by tertiary substrates. Remember our crowded dance floor analogy for SN2? Well, for SN1, those bulky groups actually help! They stabilize the carbocation that forms. The more electron-donating groups around the positive charge, the happier that carbocation is. Think of it as a group of friends rallying around someone who's feeling a bit down.

The leaving group also plays a crucial role. A good leaving group is one that's stable on its own once it leaves. Halides (like Cl-, Br-, I-) are generally good leaving groups. Hydroxide (OH-) is a terrible leaving group, but if it gets protonated (gets a hydrogen attached), it turns into water (H2O), which is an excellent leaving group! So, sometimes a little pH adjustment can make a big difference.

And what about the solvent? SN1 reactions love polar protic solvents, like water or alcohols. These solvents help to stabilize both the carbocation intermediate and the leaving group as they separate. They're like the supportive friends who are there for both halves of the breakup!

Let's Get Drawing! Putting Theory into Practice

Okay, theory is great, but the real fun (and sometimes the real head-scratching) comes when we actually have to draw the organic product. Don't worry, it's not as scary as it sounds. We'll go through it step-by-step.

Step 1: Identify Your Players

First things first, you need to identify the nucleophile and the substrate in the reaction equation. The nucleophile is usually the species with a negative charge or lone pairs of electrons (remember, they love positive charges!). The substrate is the molecule that has the leaving group attached. The leaving group is usually a halogen (like Cl, Br, I), a tosylate, or sometimes water (after being protonated).

Example: Let's say you have an ethyl bromide (CH3CH2Br) reacting with hydroxide ion (OH-).

- Nucleophile: OH- (It's got a negative charge and lone pairs!)

- Substrate: CH3CH2Br (Bromine is the leaving group here.)

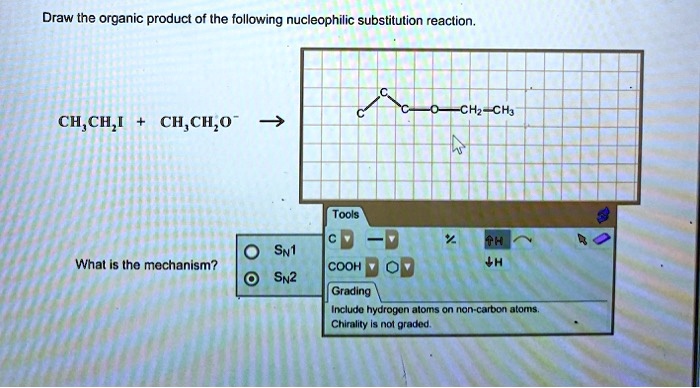

Step 2: Determine the Reaction Mechanism (SN1 or SN2?)

This is where your knowledge of substrate structure, leaving group ability, and solvent comes in handy. Ask yourself:

- Is the substrate primary, secondary, or tertiary?

- Is the leaving group a good one?

- What's the solvent?

Let's stick with our ethyl bromide and hydroxide example. Ethyl bromide is a primary substrate. Primary substrates generally favor SN2. Hydroxide is a strong nucleophile, and if we assume a polar aprotic solvent (which is common for strong nucleophiles like OH- in SN2), then SN2 is our likely winner!

Now, what if we had tert-butyl chloride ( (CH3)3CCl ) reacting with water?

- Nucleophile: H2O (Water can act as a nucleophile, though it's weaker than OH-).

- Substrate: (CH3)3CCl (Chlorine is the leaving group).

Tert-butyl chloride is a tertiary substrate. Tertiary substrates, especially with weaker nucleophiles like water, favor SN1. Water is also a polar protic solvent, which further supports SN1. So, for this one, we're going with SN1.

Step 3: Execute the Nucleophilic Attack (and Draw!)

This is the fun part where we actually draw the product. It depends on whether it's SN1 or SN2.

For SN2 Reactions:

Remember the backside attack and inversion of configuration? You’ll need to draw the nucleophile replacing the leaving group, but with the opposite stereochemistry if the carbon is chiral. If the carbon isn't chiral, it’s simpler!

Going back to our ethyl bromide and hydroxide example (SN2):

- The bromide (Br) leaves.

- The hydroxide (OH-) attacks from the back.

- The product will be ethanol (CH3CH2OH).

If we consider stereochemistry (let's imagine the carbon attached to Br was chiral, which it isn't in this simple case, but for illustration): If the Br was on a wedge, the OH would come in on a dash, and vice-versa.

Visualizing it: Imagine the carbon atom as a hub. The leaving group (Br) is attached to one spoke. The nucleophile (OH-) comes in from the opposite spoke, pushing the other spokes (the rest of the molecule) around, like a hand turning a wheel or an umbrella in the wind.

For SN1 Reactions:

First, draw the carbocation that forms after the leaving group departs. Then, draw the nucleophile attacking that carbocation.

Using our tert-butyl chloride and water example (SN1):

- The chloride (Cl) leaves, forming a stable tertiary carbocation: (CH3)3C+.

- The water molecule (H2O) attacks the positive carbon.

- This forms an intermediate where the oxygen of water is bonded to the carbon and still has its two hydrogens and a positive charge on the oxygen.

- Finally, another water molecule (or the solvent) will deprotonate the oxygen (take away one of the hydrogens), leaving behind tert-butyl alcohol: (CH3)3COH.

Remember the racemic mixture? If the carbocation carbon were chiral, the nucleophile could attack from either side, giving you a mix of both stereoisomers. If you're asked to draw the product and it's a chiral center, you'll often draw both enantiomers or indicate that a racemic mixture is formed.

Visualizing it: The leaving group just poofs away. Then, the nucleophile (even a neutral one like water) sees the positive charge and is attracted. It’s like the lonely carbocation is holding up a “Help Wanted” sign, and the nucleophile answers the call.

Step 4: Double-Check Your Work!

Before you declare victory, take a moment to review. Did you:

- Identify the correct nucleophile and leaving group?

- Choose the appropriate mechanism (SN1 or SN2)?

- Draw the nucleophile replacing the leaving group?

- Consider stereochemistry if applicable?

- Make sure all atoms have a full valence shell (or the correct charge)?

It’s always a good idea to count your atoms before and after the reaction to make sure nothing’s gone missing. Sometimes, a sneaky little atom might try to escape!

A Few More Fun Details to Spice Things Up

We've covered the basics, but there are always nuances in chemistry, right? For instance, sometimes you can have both SN1 and SN2 pathways happening simultaneously, especially with secondary substrates. It’s like a choose-your-own-adventure novel for molecules!

Also, remember that strong bases are usually good nucleophiles, but sometimes they can also act as bases, leading to an elimination reaction instead of substitution. It's like a competitor showing up to the dance and trying to start a whole different kind of party! So, context is key.

And the leaving group! A really, really good leaving group makes substitution much more likely. Think of things like tosylates (OTs) and mesylates (OMs) – they are superstars at leaving. They are basically anions that are very stable on their own, so they’re happy to take off.

Sometimes, the "nucleophile" might look a bit unassuming, like an alcohol or even water. These are weaker nucleophiles and tend to favor SN1 reactions, especially if the substrate is prone to forming a stable carbocation. They’re not as aggressive as something like OH- or CN-.

When you’re drawing, don’t be afraid to use wedges and dashes to show the 3D structure. It’s what makes organic chemistry so visually interesting!

And if you get stuck, go back to the core principles. What’s attacking what? What’s leaving? Is the environment conducive to a one-step or a two-step process? These questions are your compass.

The Big Picture and a Smile

So, why is all this important? Because nucleophilic substitution reactions are everywhere in organic chemistry! They’re fundamental to making new molecules, from the medicines that heal us to the materials that build our world. Understanding them is like getting a master key to unlock countless chemical transformations.

Don’t get discouraged if you don’t get it perfectly the first time. Chemistry is a journey, not a destination. Every reaction you draw, every mechanism you figure out, is a step forward. Each correct product you draw is a small victory, a testament to your growing understanding and your ability to think like a molecule.

Keep practicing, keep observing, and most importantly, keep that curiosity alive. The world of organic chemistry is full of amazing discoveries waiting for you to uncover them. So go forth, draw those products with confidence, and remember that you’re not just drawing molecules; you’re visualizing the elegant dance of chemistry. And that, my friends, is pretty darn cool. Keep smiling, keep learning, and happy drawing!