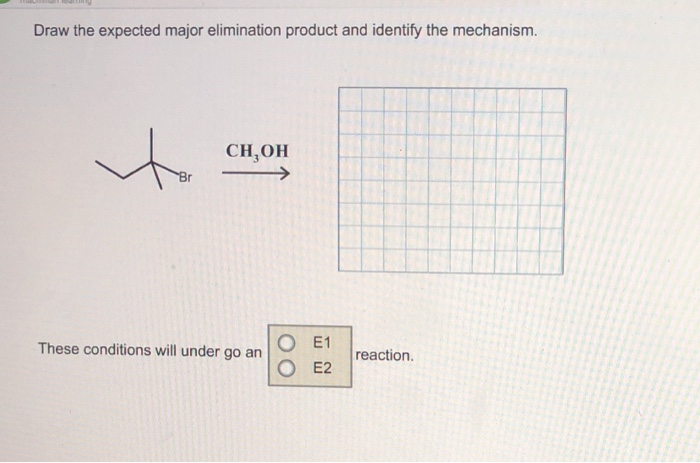

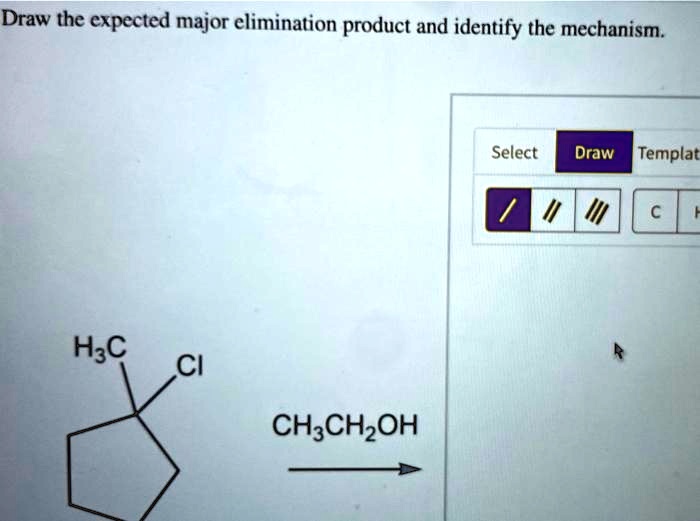

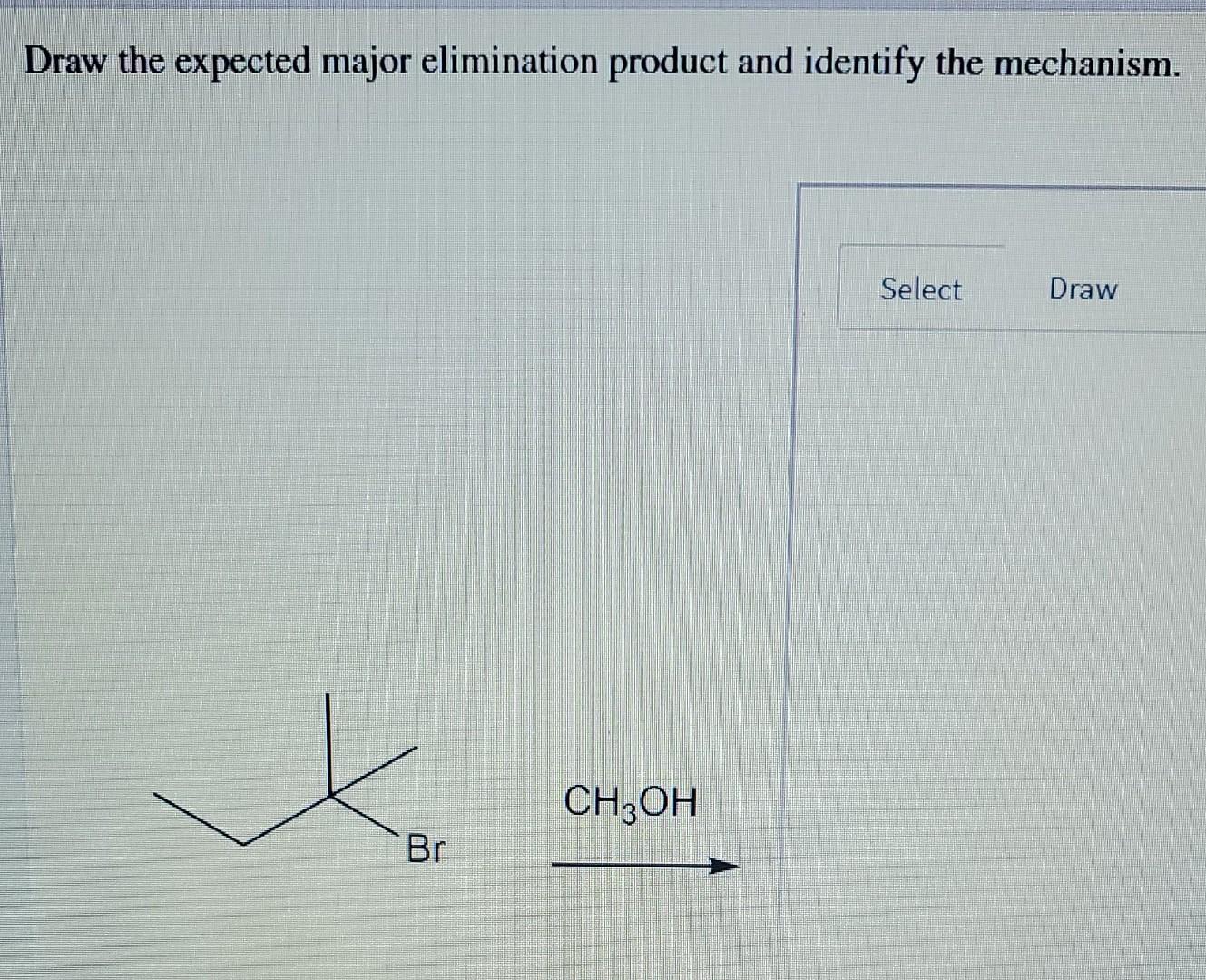

Draw The Expected Major Elimination Product And Identify The Mechanism

Okay, so picture this: it’s late at night, I’m hunched over my chemistry textbook, fueled by questionable amounts of lukewarm coffee and the desperate hope of understanding… well, everything. My eyes are practically glued to a diagram of this molecule, a big ol’ thing with a bunch of carbons and hydrogens and a tantalizing hint of a double bond about to pop into existence. Suddenly, a wild thought hit me: how does this even happen? It’s like watching a magic trick where you see the rabbit disappear, but you have no clue about the sleight of hand. That, my friends, is where we’re diving into today: the expected major elimination product and the mechanism behind it all. Because let's be real, understanding how things break apart is just as fascinating (and sometimes more chaotic!) than watching them form.

You know, it's funny how we often focus on building things up in chemistry, creating complex molecules from simpler ones. But the dismantling? The controlled demolition? That’s a whole other ballgame. And it’s crucial! Without elimination reactions, we wouldn't have the building blocks for so many other important processes. Think of it as the ultimate "reset" button for molecules. Sometimes, you just gotta shed some baggage to become something new and exciting, right?

Unpacking the "Elimination" Concept

So, what exactly is an elimination reaction? In the simplest terms, it's when you remove two atoms or groups from adjacent atoms in a molecule, usually forming a pi bond (like a double or triple bond). Think of it like this: you’ve got two people holding hands, and in an elimination reaction, they both let go, and suddenly, there’s a new connection between where their hands used to be. Pretty neat, huh?

This often happens with molecules that have a "leaving group." A leaving group is basically an atom or a group of atoms that’s just itching to depart. It’s like that one friend at a party who’s always looking for an excuse to bail. Good for them, I guess!

The most common types of elimination reactions we encounter in organic chemistry are E1 and E2. They sound a bit like secret agent codes, don't they? "Agent E1, your mission, should you choose to accept it…" But don't let the fancy names fool you. They're just different ways of achieving the same goal: getting rid of some molecular clutter and making room for a double bond.

The E1 Reaction: The "Wait and See" Approach

Let’s start with E1, the E is for Elimination, and the 1 signifies a unimolecular rate-determining step. This means the speed of the reaction depends only on the concentration of one molecule. Intriguing, right?

E1 reactions are often associated with tertiary and secondary substrates, especially in acidic conditions or with weak nucleophiles that can also act as bases. The mechanism unfolds in two distinct steps:

Step 1: Leaving Group Departs – The Carbocation is Born!

This is the slow, rate-determining step. The leaving group, bless its heart, just decides to pack its bags and leave. It takes its bonding electrons with it, creating a positively charged carbon atom – a carbocation. Imagine your molecule is a tightly-knit group of friends, and one of them just suddenly moves to another city without much warning. The remaining friends are left feeling a bit… unbalanced.

This carbocation is an intermediate. It’s not the starting material, and it’s not the product, but it’s a crucial stepping stone. Carbocations are generally unstable, so they don’t hang around for long. The more stable the carbocation, the easier this first step will be. Tertiary carbocations are the most stable (due to hyperconjugation, if you want to get fancy), followed by secondary, and then primary (which rarely form via E1). So, if you’ve got a tertiary or secondary alcohol that’s been protonated (meaning an H+ has attached to the oxygen, making water a better leaving group), you’re prime territory for an E1 reaction.

Step 2: Proton Removal – The Pi Bond Appears!

Once the carbocation is formed, things pick up the pace. A base (which can be the solvent itself, like water or alcohol, or another molecule present) swoops in and grabs a proton (H+) from an adjacent carbon atom. This adjacent carbon is called a beta-carbon (the carbon with the positive charge is the alpha-carbon). When the base pulls off that proton, the electrons from the C-H bond shift over to form a new pi bond between the alpha and beta carbons. Voila! We have an alkene, our elimination product.

This second step is fast because it’s driven by the formation of the stable pi bond. The base is the unsung hero here, doing the final bit of magic to complete the transformation. It’s like the stagehand who quickly rearranges the props after the main act.

The E2 Reaction: The "All at Once" Action

Now, let's talk about E2. The E is still Elimination, but the 2 means it's bimolecular. This means the rate of the reaction depends on the concentration of two molecules: the substrate and the base. This is an “all-in-one-go” kind of reaction. There are no intermediates, no lingering carbocations. Everything happens in a single, concerted step.

E2 reactions are favored by strong, bulky bases and typically occur with primary, secondary, and tertiary alkyl halides or similar compounds with good leaving groups. Think of a really enthusiastic friend who tackles a task with you, from start to finish, no breaks. That's E2!

The Concerted Mechanism: A Dance of Departure and Formation

In an E2 reaction, the base attacks a beta-proton simultaneously as the leaving group departs and the pi bond forms. It’s a beautifully coordinated effort. The base and the leaving group are essentially on opposite sides of the molecule, and they perform a sort of molecular ballet.

For the E2 reaction to proceed efficiently, there’s a crucial geometrical requirement: the beta-hydrogen and the leaving group must be in an anti-periplanar arrangement. What on earth does that mean? It means they need to be in the same plane, but on opposite sides of the C-C bond, with about 180 degrees between them. Think of it like trying to pass a baton in a relay race; it’s much easier when you’re both facing the same direction and can smoothly pass it. If they aren't anti-periplanar, the reaction might be slower or might not happen at all.

The strength of the base is key here. Strong bases are much better at abstracting that beta-proton, initiating the whole chain reaction. Sterically hindered bases (bulky ones) are often preferred because they are less likely to act as nucleophiles and attack the alpha-carbon (which would lead to a substitution reaction, SN2). They are just better at sniffing out and grabbing those accessible beta-hydrogens.

Predicting the "Expected Major Elimination Product": Zaitsev vs. Hofmann

Alright, so we know how these reactions happen. But what about what they make? This is where things get a little bit like a choose-your-own-adventure story. Sometimes, a molecule can eliminate in more than one way, leading to different possible alkene products. We usually want to know which one will be the major product.

This is where two important rules come into play: the Zaitsev’s Rule and the Hofmann’s Rule. They sound like characters from a vintage detective novel, don’t they? “Ah, Inspector Zaitsev, what have we here?”

Zaitsev's Rule: The Most Substituted Alkene Wins!

Generally, elimination reactions tend to favor the formation of the more substituted alkene. This is Zaitsev’s Rule. A more substituted alkene has more alkyl groups attached to the double bond carbons. For example, a trisubstituted alkene is more stable than a disubstituted alkene, which is more stable than a monosubstituted alkene.

Why is this the case? It’s all about stability. The more alkyl groups there are attached to the double bond, the more hyperconjugation can occur. Hyperconjugation is a stabilizing interaction where the electrons in adjacent sigma bonds (like C-H or C-C bonds) can overlap with the empty p-orbital of the carbocation (in E1) or the pi system of the alkene. It’s like giving the molecule a little extra energetic support. So, nature tends to go for the most stable option, the most substituted alkene.

This is usually the outcome with smaller, less hindered bases and under conditions favoring E1 reactions. In E2, Zaitsev products are often favored with strong, unhindered bases like ethoxide (EtO-) or hydroxide (OH-).

Let’s say you have a molecule where you can form a double bond between carbon 1 and 2, or between carbon 2 and 3. If the double bond between 1 and 2 results in a more substituted alkene (meaning more carbons are attached to carbons 1 and 2), that’s likely to be your Zaitsev product.

Hofmann's Rule: The Less Substituted Alkene Takes the Crown!

However, there are exceptions to every rule, and Zaitsev’s Rule is no different. Sometimes, the less substituted alkene is the major product. This is Hofmann’s Rule. This typically happens when you have bulky, sterically hindered bases or with certain leaving groups. Think of a really large, clumsy base trying to get into a crowded space. It might prefer to grab an easier-to-reach proton on a less substituted carbon.

Common culprits for favoring Hofmann elimination are bases like potassium tert-butoxide (KOtBu) or amines like DBU (1,8-Diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene). These bases are so big that they struggle to access the more hindered beta-hydrogens. They’ll go for the proton on the carbon with fewer alkyl substituents, leading to the less substituted alkene as the major product.

Also, certain leaving groups, like ammonium salts or sulfonium salts, are better leaving groups when deprotonated from less substituted positions, which can also lead to Hofmann products. So, if you’re using a big, intimidating base, keep an eye out for the Hofmann product!

Putting It All Together: A Hypothetical Scenario

Let’s try a quick example to solidify this. Imagine we have 2-bromobutane. We want to react it with a base.

If we use a strong, unhindered base like sodium ethoxide (NaOEt) in ethanol, we are likely looking at an E2 elimination (because it’s a strong base). Now, where can the double bond form? We have beta-hydrogens on carbon 1 and carbon 3.

- Elimination between C1 and C2 would give but-1-ene (monosubstituted).

- Elimination between C2 and C3 would give but-2-ene (disubstituted).

According to Zaitsev's Rule, the more substituted alkene is favored. But-2-ene is disubstituted, while but-1-ene is monosubstituted. Therefore, but-2-ene would be the major product. (Note: But-2-ene can exist as cis and trans isomers, and the trans isomer is generally more stable and thus favored). The mechanism would be E2, with the ethoxide ion abstracting a proton from either C1 or C3, simultaneously pushing out the bromide ion and forming the double bond. Since C3 is less hindered and leads to the more substituted alkene, it will be the preferred site of deprotonation, leading to but-2-ene as the major product.

Now, what if we used a bulky base, like potassium tert-butoxide (KOtBu), in tert-butanol? Again, we’re likely looking at an E2 elimination. However, this time, our bulky base will have trouble accessing the proton on C3, which is adjacent to two carbons. It will much more readily grab the proton from C1, which is only attached to one carbon.

In this case, the elimination between C1 and C2 becomes favored, leading to but-1-ene as the major product, following Hofmann’s Rule. The bulky tert-butoxide ion simply can’t get around to the more crowded C3 to snatch that proton.

The Takeaway Message

So, there you have it! The world of elimination reactions, from the step-by-step process of E1 to the all-in-one dance of E2. And the art of predicting the major product, whether it’s the Zaitsev’s rule favoring the most substituted alkene or the Hofmann’s rule tipping the scales towards the least substituted, depending on the base and sometimes the leaving group.

It’s a bit like being a chemist-detective. You examine the clues – the structure of the molecule, the strength and size of the base, the reaction conditions – and then you deduce the most likely outcome. It’s not always straightforward, and sometimes you get a mixture of products, but understanding these fundamental principles gives you a powerful tool for predicting what will happen.

So next time you see a molecule with a good leaving group and a potential for alkene formation, don't just stare blankly! Think about the mechanism. Is it E1 or E2? What kind of base is it? And then, channel your inner Zaitsev or Hofmann to predict that glorious, expected major elimination product. Happy eliminating!