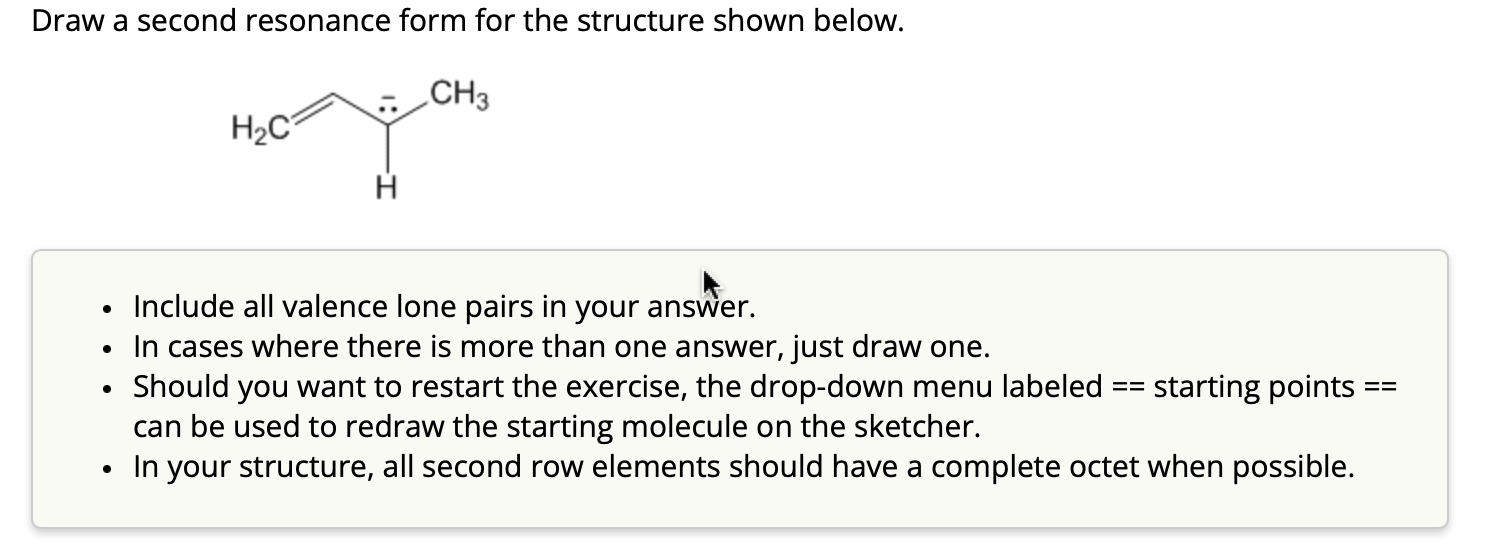

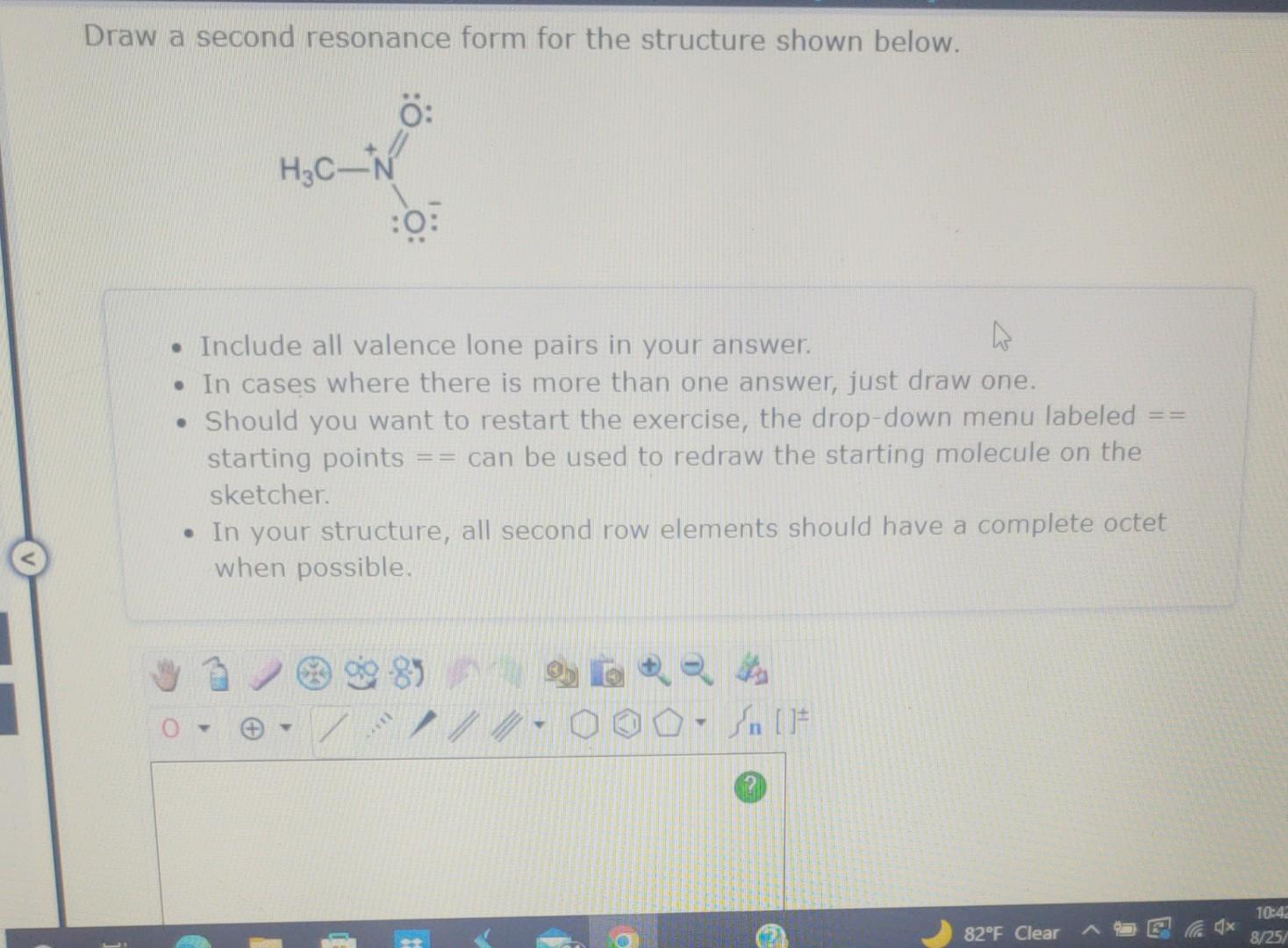

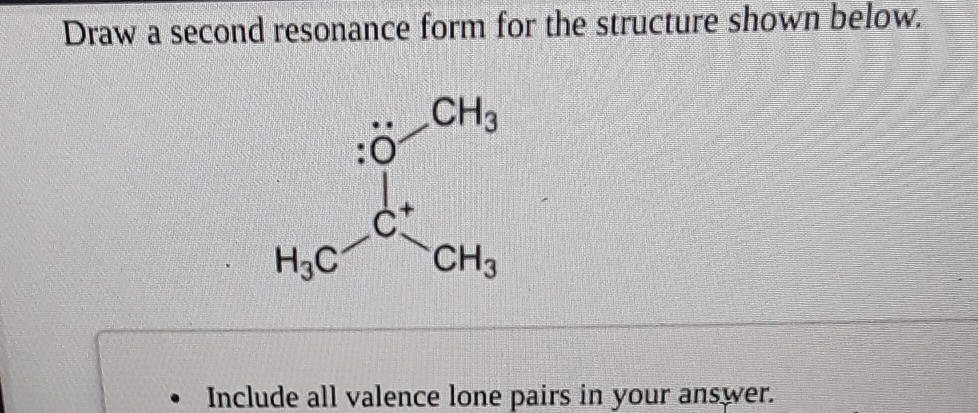

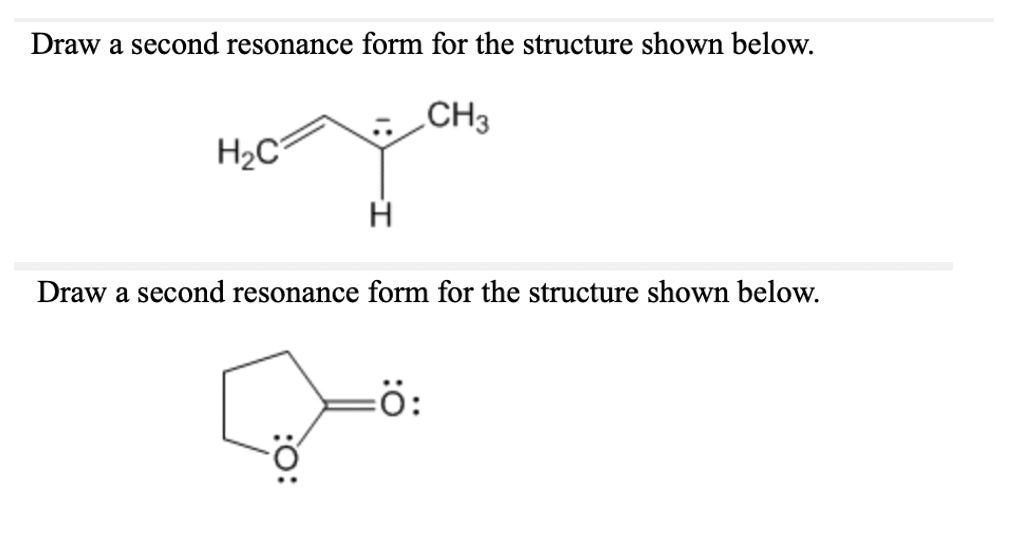

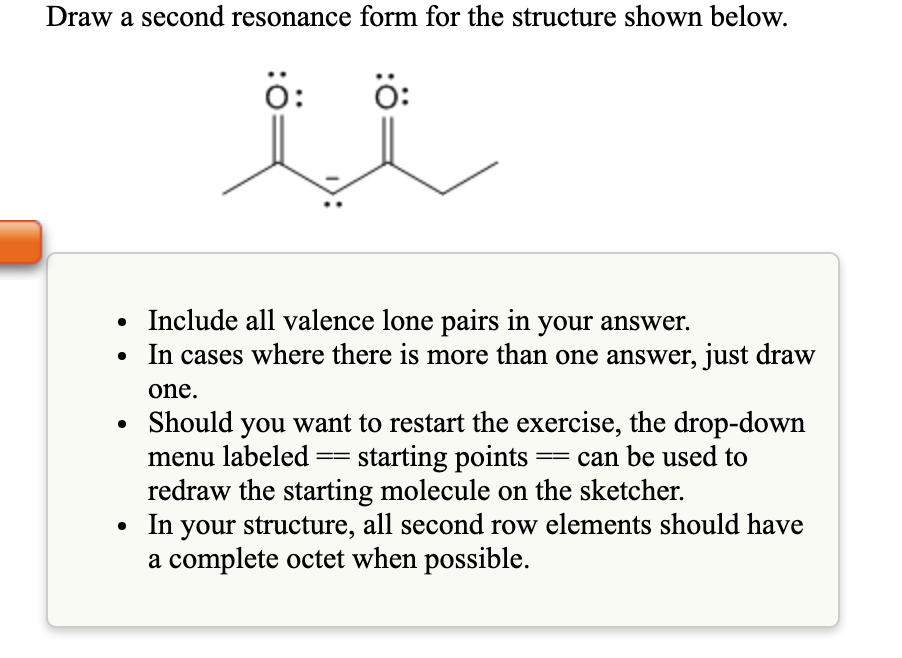

Draw A Second Resonance Form For The Structure Shown Below.

Hey there, awesome chemists and curious minds! So, we've got a super cool puzzle to tackle today, and it's all about making our molecules do a little happy dance. We're going to dive into the wonderful world of resonance structures. Don't let that fancy word scare you; it's basically like giving our molecule a few different "outfits" to wear, depending on where the electrons decide to hang out. Think of it like a chameleon, but with electrons instead of colors!

Our mission, should we choose to accept it (and trust me, you totally should because it's going to be fun!), is to draw a second resonance form for a specific structure. Now, I can't actually show you the structure here, since we're in text-land, but imagine it's a molecule that's feeling a little indecisive about where its electrons want to be. You know, like when you can't decide if you want pizza or tacos for dinner. It's that kind of vibe.

Before we jump into drawing, let's have a quick refresher on what resonance is all about. It's not like our molecule is actually changing its shape or bonds every second. Instead, resonance structures are like different snapshots of the same molecule. The real molecule is actually a blend, a sort of average, of all these different structures. We call this the resonance hybrid. It's like getting the best of all worlds, which, let's be honest, is what we all strive for in life, right?

The key players in this electron-shuffling game are pi electrons and lone pairs. These are the flexible ones, the electrons that aren't tied down in a single, rigid bond. They're the free spirits of the molecule, always ready for an adventure. Think of them as the electrons that are a bit more "social" and willing to move around to make everyone else in the molecule a bit happier and more stable.

So, how do we get from one resonance structure to another? We use these handy-dandy curved arrows. These arrows are like little pointers, showing us the direction of electron movement. They're super important, so let's make sure we treat them with the respect they deserve. A curved arrow starts at the "source" of the electron pair (either a lone pair or a pi bond) and points to where those electrons are going to end up. It's like telling a story with our electrons, showing us their journey!

Now, let's get down to business with our specific structure. Imagine we have a molecule. For us to be able to draw a second resonance form, our initial structure needs to have some of these mobile electrons. This usually means we're looking for things like:

Things to Look For in Your Starting Structure:

- Double or Triple Bonds: These are prime real estate for pi electrons, just waiting to jump ship.

- Lone Pairs of Electrons: Those little pairs hanging out on atoms are like little packets of potential energy, ready to move.

- Adjacent Atoms with Opposite Charges: Sometimes, a positive charge next to a negative charge can encourage some electron migration.

- Atoms with Incomplete Octets: Atoms that are a bit "hungry" for electrons can draw them in, creating new resonance forms.

Okay, so let's pretend our starting structure looks something like this. (Again, I'm just describing it, so bear with my descriptive powers!) Let's say we have a molecule where there's a double bond next to an atom with a lone pair. Or maybe a double bond next to a positive charge. These are classic setups for resonance!

Let's take a common scenario: a double bond adjacent to a lone pair. Imagine a carbon atom with a double bond attached to another atom, and that second atom has a lone pair of electrons sitting on it. This is like a molecular playground! The lone pair is just itching to get involved.

To draw our second resonance form, we're going to use our trusty curved arrows. The first move is usually to take those lone pair electrons and use them to form a new pi bond between the atom that had the lone pair and the atom that was part of the original double bond. So, the lone pair "pushes" its way into forming a double bond.

What happens next? Well, you can't just create a double bond out of thin air without something giving way. The original double bond, which was a pi bond, has to break. Those electrons from the original double bond then have to go somewhere. Often, they'll hop onto the atom that was originally at the other end of that double bond, turning it into a negative charge. It's a bit of a give-and-take, a molecular swap meet!

Let's visualize this. If we have O=C-N: with a lone pair on the nitrogen, the lone pair on nitrogen can push into the C=O bond, forming a C-O single bond and moving the pi electrons from the C=O to the oxygen, giving it a negative charge. The nitrogen then forms a double bond with the carbon. So, our structure would change from O=C-N: to O:-C=N. See? The electrons just did a little jig!

Another classic scenario is a double bond next to a positive charge. Imagine a carbon atom with a double bond next to a carbon atom that's missing an electron and has a positive charge. The pi electrons from the double bond are like, "Hey, that guy over there looks lonely!" So, they decide to move and form a new bond with the positively charged carbon.

In this case, a pair of electrons from the pi bond moves to form a new sigma bond with the positively charged carbon. This means the original double bond becomes a single bond. The atom that lost the pi bond electrons will now have a positive charge, and the atom that gained them will now be neutral (or have a different formal charge, depending on the specifics). It's like the double bond sacrifices itself to save the day for the positive guy!

Think about it like this: if you have a situation like C=C⁺, the pi bond can break and the electrons can move to form a bond with the positive carbon. So, you'd end up with -C-C. The carbon that was part of the double bond and now has only a single bond to its neighbor will pick up the positive charge. It’s a transfer of responsibility, really.

When drawing resonance structures, there are a few golden rules we *must follow. These aren't just suggestions; they're the laws of the resonance land!

The Sacred Rules of Resonance Drawing:

- The Atoms Themselves Don't Move: Only the electrons are doing the cha-cha. The actual atoms stay put.

- The Total Charge Must Remain the Same: If your starting molecule has a -1 charge, all its resonance forms must also have a -1 charge. No creating or destroying charge!

- The Number of Unpaired Electrons Should Remain the Same: Radicals don't magically become non-radicals and vice-versa through resonance.

- Follow the Curved Arrows (and they should make chemical sense): Each arrow shows the movement of one electron pair (two electrons).

Let's try another one. Imagine you have a molecule with a double bond and a single bond next to it, and the single bond atom has a lone pair. For example, a C=C-O: structure with two lone pairs on the oxygen. The lone pair on the oxygen can push to form a double bond between the oxygen and the carbon it's single-bonded to. This forces the original C=C double bond to break. The electrons from the C=C double bond then move to the other carbon, giving it a negative charge.

So, you'd go from C=C-O: (with two lone pairs on O) to -C:-C=O (with one lone pair on O, and the other pair forming the new double bond). See how the electrons rearranged themselves? It’s a beautiful symphony of electron movement!

Sometimes, you might have a situation where you have a double bond within a ring system. These are often excellent candidates for resonance. The pi electrons in the double bond can delocalize, meaning they spread out over multiple atoms. This delocalization makes the molecule more stable. Think of it like sharing is caring, but for electrons!

If you have a structure where a double bond is adjacent to another double bond (like in a conjugated system), you can often move those pi electrons around. For example, in butadiene (CH2=CH-CH=CH2), the pi electrons can shift. One double bond can move to become a single bond, and the other single bond can become a double bond, and so on. This creates a whole series of resonance forms where the pi electron density is spread out across all four carbon atoms.

It’s important to remember that not all resonance structures contribute equally to the overall hybrid. Some are more "important" or "stable" than others. Generally, the resonance structures that have:

Factors Affecting Resonance Structure Stability:

- More covalent bonds

- A full octet on most atoms

- Less separation of charge

- Negative charge on more electronegative atoms (like Oxygen or Nitrogen) and positive charge on less electronegative atoms (like Carbon)

are considered more significant contributors to the resonance hybrid. It's like having a favorite outfit – some resonance forms just "fit" the molecule better and are more dominant.

So, for our mystery structure, what we need to do is identify those movable electrons – the lone pairs and the pi electrons. Then, we'll draw our curved arrows to show how they can rearrange themselves to form new bonds and shift charges. Remember, we’re not creating anything new; we’re just showing different valid arrangements of the same electrons.

Let's say your starting structure has a double bond between two carbons, and one of those carbons is also attached to an oxygen atom with a lone pair. If the oxygen is double-bonded to that carbon (C=O), and there's a lone pair on the oxygen, you can often move a lone pair to form a double bond, or move pi electrons. It really depends on the exact arrangement and the formal charges.

But the core idea is always the same: find the flexible electrons, show their movement with curved arrows, and see where they end up. Don't be afraid to try different movements! Sometimes, there's more than one way to move those electrons. That’s the beauty of resonance – it’s all about exploring the possibilities and finding the most stable arrangements.

And hey, if you mess up, that’s totally okay! Chemistry is all about experimenting and learning. Just erase, redraw, and try again. You're building a deeper understanding of how molecules behave, and that's pretty darn cool.

So, take a deep breath, look at your structure, and channel your inner electron whisperer. You've got this! The world of molecules is full of fascinating dances and rearrangements, and understanding resonance is like unlocking a secret language. Keep practicing, keep experimenting, and most importantly, keep that curiosity alive. You're doing great things, and every resonance structure you draw is a step closer to mastering the art of chemistry. Go forth and resonate, my friends!