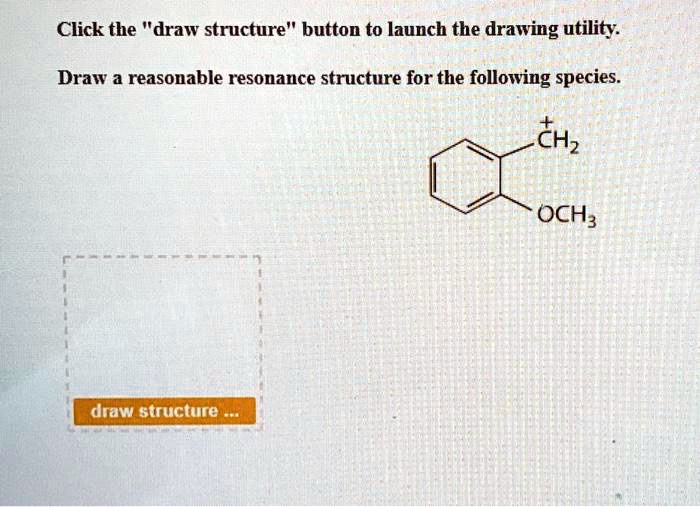

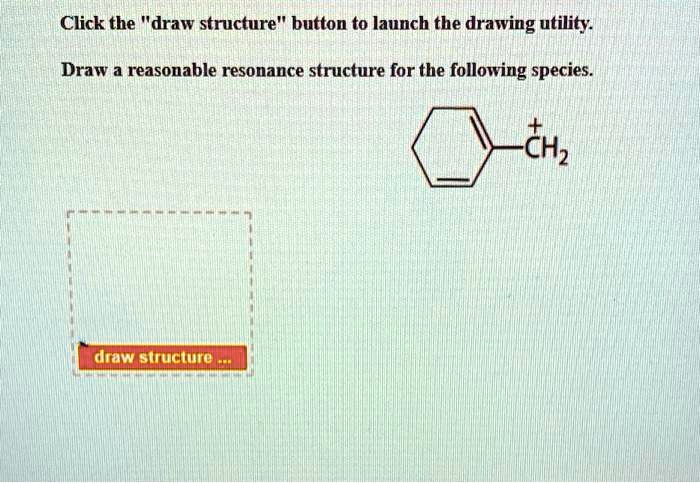

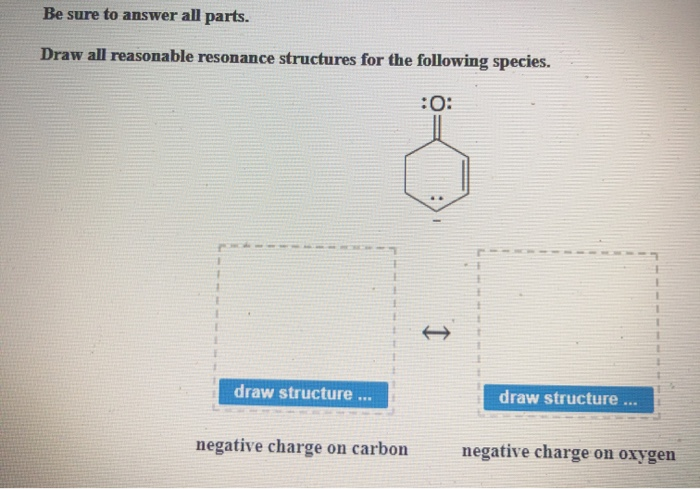

Draw A Reasonable Resonance Structure For The Following Species

Alright folks, gather 'round, grab a virtual croissant, and let's dive headfirst into the wonderfully wacky world of chemistry. Specifically, we're talking about something called "resonance structures." Now, before your eyes glaze over and you start contemplating the nutritional value of that stale donut, hear me out. This isn't your grandma's boring chemistry lecture. This is more like a secret handshake for molecules, a way they wink at each other and say, "Psst, I'm not exactly what I seem."

Imagine you're trying to describe a particularly chameleon-like friend. You know the type. One minute they're all jazz hands and sequins, the next they're in a sensible cardigan discussing stamp collecting. You could draw a picture of them in sequins, but that's not the whole story, is it? They're also in the cardigan, and maybe a superhero costume on Tuesdays. Resonance structures are chemistry's way of saying, "Yeah, this molecule's a bit of a shapeshifter."

Our mission today, should you choose to accept it (and you should, there are cookies involved, metaphorically speaking), is to draw a reasonable resonance structure for a specific, yet-to-be-revealed, chemical critter. Think of it as a molecular makeover, where we rearrange some electrons and see what fabulous new look we can achieve. It's all about the delocalization of electrons, which is a fancy way of saying they're not stuck in one place, like a shy kid at a party. Nope, they're out there, mingling, spreading the love (and the negative charge, probably).

Now, let's set the scene. We're going to be looking at a species. Don't worry, it's not some terrifying beast from the deep ocean. In chemistry, a "species" is just a molecule or an ion. Think of it as its full name, like "Mr. Reginald P. Fancypants Esquire." We're going to be drawing Mr. Fancypants in a few different outfits. And the most important rule? The atoms themselves never move. They're like the furniture in the room. We're just shuffling the pillows and adjusting the curtains. The electrons? They're the wild dancers, free to roam.

The Big Reveal: Our Star Performer!

Drumroll, please! (Imagine a drummer with a very tiny drum). Today's species is the nitrate ion, also known as NO3-. If you've ever encountered fertilizer, or those fancy little fireworks that go "poof," you've met the nitrate ion's family. It's basically a nitrogen atom chilling with three oxygen atoms, and it's carrying a bit of extra baggage – that little superscript minus sign, the negative charge.

Here's the deal: Nitrogen loves to make bonds, and oxygen loves to make bonds. They're like that couple that can't get enough of each other. But with three oxygens and only one nitrogen, things get a little crowded, and the electrons have to get creative. They can't all just be loyal to one oxygen; they have to share the love, or rather, the negative charge.

The Rules of the Resonance Game

Before we grab our virtual pencils, let's lay down some ground rules. These are like the unwritten rules of a good party: no hogging the snacks, and definitely no starting a food fight with the electrons.

1. Electrons move, not atoms. I know I said it before, but it's that important. The skeleton of the molecule – the arrangement of atoms – stays put. Think of it as a rigid gingerbread house; we're just painting the icing differently.

2. We're only moving electrons that are already there. No conjuring electrons out of thin air. No pulling them from the pockets of unsuspecting atoms. We're working with the electron pool we've got. This usually means moving pi electrons (the ones in double or triple bonds) or lone pair electrons (those little guys hanging out on atoms, looking for a dance partner).

3. The total charge must remain the same. If our nitrate ion starts with a -1 charge, all its resonance structures must also have a -1 charge. It's like showing up to a potluck; you bring your dish, and you leave with the same amount of food you brought (ideally, anyway).

4. We aim for the best possible Lewis structure. This means trying to give as many atoms as possible a full octet (eight electrons in their outer shell), like a happy, complete family. Also, we prefer fewer formal charges, and if there are charges, we put the negative ones on the more electronegative atoms (the ones that are greedier for electrons, like oxygen).

Let's Get Our Hands Dirty (Electronically Speaking)

So, we have our nitrate ion, NO3-. The nitrogen is in the middle, bonded to three oxygens. To start, let's draw a basic Lewis structure. Nitrogen typically forms 5 bonds (it's in group 5 of the periodic table), and each oxygen wants to form 2 bonds (group 6). We also have that extra electron from the negative charge. When you do the math (which is less scary than it sounds, like doing a crossword puzzle with a dictionary), you'll find that one oxygen will have a double bond to the nitrogen, and the other two will have single bonds.

Here’s the initial setup. Imagine Nitrogen (N) in the center. One Oxygen (O) is connected with a double bond (two lines). Two other Oxygens are connected with single bonds (one line). We'll have some lone pairs on the oxygens, and that negative charge needs to be distributed.

The oxygen with the double bond will have two lone pairs. The oxygens with the single bonds will have three lone pairs each. This looks pretty good, everyone's got a full octet! But here’s the trick: that double bond? It's not permanently fixed to that one oxygen.

This is where resonance swoops in, like a superhero in a cape made of electron clouds! What if we moved those electrons around?

The Resonance Shuffle!

Let's take the double bond from the top oxygen and "push" those electrons over to one of the single-bonded oxygens. We can do this by moving a pair of electrons from the double bond to become a lone pair on the top oxygen. Then, we can take a lone pair from one of the single-bonded oxygens and use it to form a new double bond with the nitrogen.

So, in our first resonance structure, let's say Oxygen A has the double bond. In our second structure, we can move that double bond to Oxygen B. This means Oxygen A now has a single bond and three lone pairs, and Oxygen B now has a double bond and two lone pairs. Oxygen C, which had a single bond, still has a single bond and three lone pairs. The total number of bonds and lone pairs, and the overall negative charge, must be conserved!

You'll see that each of these structures has a different oxygen carrying the double bond. We draw these structures separated by a double-headed arrow (<=>). This arrow doesn't mean it's flipping back and forth like a switch. It means the real molecule is a blend, a hybrid, of all these possible structures. It’s like having a vote where every option gets some of the credit!

We can draw a third resonance structure where the double bond is on Oxygen C. So, the top oxygen has a single bond, Oxygen B has a single bond, and Oxygen C has the double bond. Again, we're just shuffling those pi electrons and lone pairs around. Remember, the nitrogen stays in the middle, and the three oxygens stay attached to it.

The Verdict: What's the Real Nitrate Ion?

So, we've drawn three reasonable resonance structures for the nitrate ion. In each one, one oxygen has a double bond and two lone pairs, while the other two oxygens have single bonds and three lone pairs. And importantly, the negative charge is distributed across the molecule. In reality, the nitrate ion doesn't have one oxygen that's "special" and has the double bond. Instead, all three N-O bonds are actually identical, somewhere between a single and a double bond. The negative charge is shared equally among the three oxygens. It's like a perfectly fair distribution of pizza slices, no one gets a bigger piece!

This delocalization of electrons is what makes molecules stable. If electrons were all stuck in one place, they'd be a lot more reactive. But by spreading them out, the nitrate ion becomes a bit more chill, a bit more unbothered. It's the chemical equivalent of a deep, cleansing breath.

So, the next time you see a chemical formula, remember that it might be a bit of a chameleon. And drawing resonance structures is just our way of appreciating all the different, equally valid, "outfits" a molecule can wear. It's a beautiful dance of electrons, a secret language, and frankly, a lot more fun than doing laundry. Now, about those metaphorical cookies...