Define Inactivation As It Applies To A Voltage-gated Sodium Channel

Hey there! So, we’re chatting about sodium channels, right? Those little gatekeepers of the neuron party. We’ve talked about how they open up when they get the signal, letting all those precious sodium ions come flooding in. It’s like a VIP club opening its doors, and sodium is the hottest guest. But what happens after the party gets a little too wild? That’s where our buddy inactivation comes in, and trust me, it’s way more interesting than it sounds. Think of it as the bouncer who gently, but firmly, tells the rowdy guests, "Okay, time to take a breather, guys."

Imagine this: A neuron is chilling, minding its own business, when BAM! A signal hits. This signal is like a text message saying, "Party at the neuron tonight!" The voltage-gated sodium channel, that cool dude we’ve been talking about, gets all excited. Its gate, which was closed tight, suddenly pops open. It’s like a secret handshake that only the right voltage can trigger. And when it opens, it’s not just a little crack. Oh no. It’s a full-on, red-carpet-rolling-out kind of opening. Sodium ions, those little charged particles, are like a stampede of eager party-goers rushing into the neuron. This influx of positive charge is what makes the inside of the neuron more positive, kicking off that exciting thing called an action potential. It's the spark that ignites the whole electrical conversation!

So, the sodium ions are having a blast, flooding in, making the inside of the cell all positive and bubbly. The neuron is basically buzzing with excitement. But here’s the thing, and this is where our friend inactivation struts onto the scene: this open state, while super important for the initial "whoop whoop!" of the action potential, can't last forever. If the channel just stayed wide open, you'd have sodium pouring in indefinitely. That would be like a never-ending mosh pit, and honestly, the neuron would probably short-circuit. We don't want a neuron meltdown, do we? That would be a real buzzkill. So, nature, in its infinite wisdom (and sometimes with a good dose of dramatic flair), has a built-in way to shut things down, but not in a permanent way. It’s more like a temporary "hold on a sec."

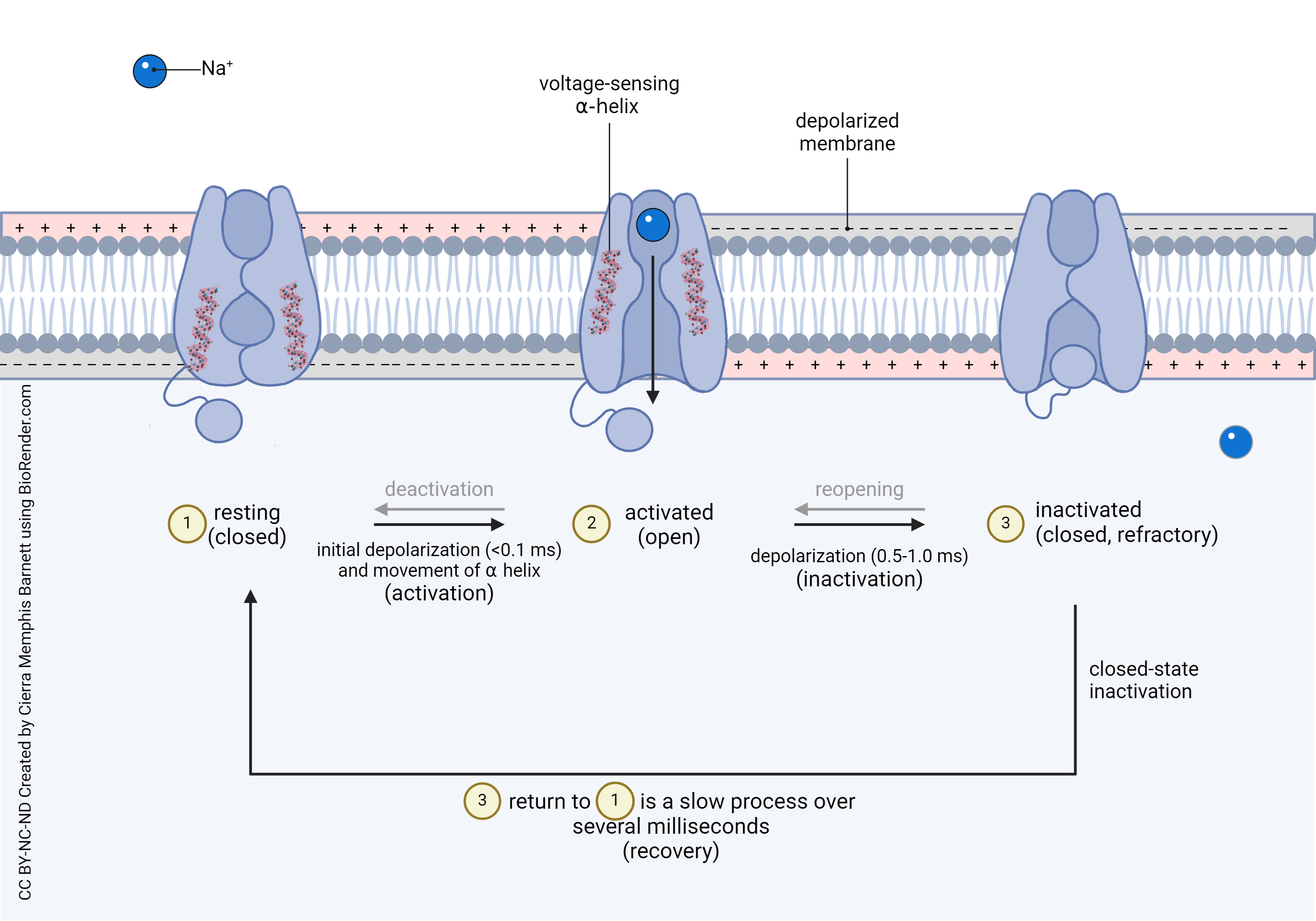

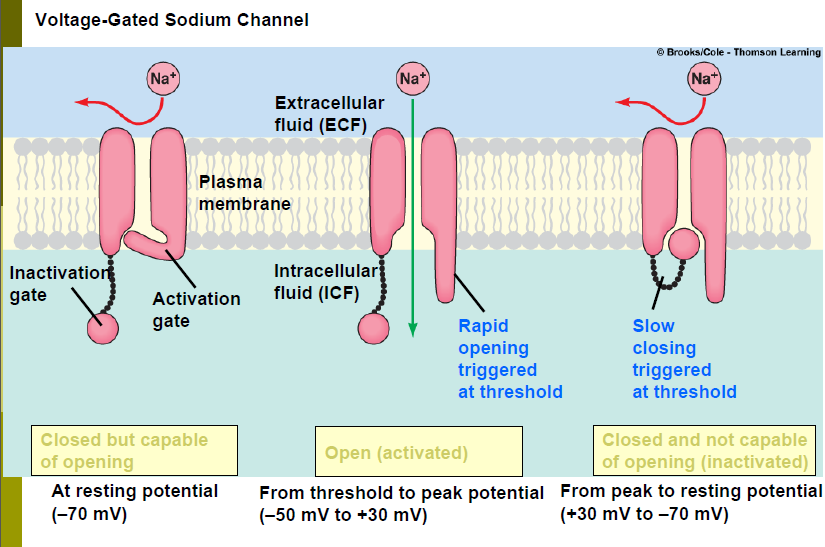

This is where the concept of different states for our sodium channel gets really cool. We’ve got the closed state, where it’s just waiting for its cue. Then we have the open state, the exciting part where ions are flowing. And then, poof, we enter the inactivated state. Think of it like a special, temporary lockdown. The channel hasn’t broken; it’s not permanently out of commission. It's just… taking a break. A really important, very specific kind of break. It's like the channel put on a little "Do Not Disturb" sign, but it’s a very sophisticated, molecular-level sign. It’s not just passively closing; there’s an active process happening here. It’s like the channel itself is deciding, "You know what? That was fun, but I need a moment."

So, what exactly is this inactivation? In simple terms, it's a change in the channel's structure that stops sodium ions from passing through, even if the electrical signal that initially opened it is still present. It's like the gate slams shut again, but for a different reason and in a different way than when it was just initially closed. Picture it like this: the channel has a little 'plug' or 'lid' that swings into place, physically blocking the pore through which the sodium ions were zooming. This plug is usually a part of the channel protein itself, and when the channel is in its active, open state for a short while, this plug gets nudged into position. It’s like a self-sabotage mechanism, but a very necessary one for the neuron's survival. So clever, right?

This inactivation is super important for a couple of reasons. First, it helps to ensure that the action potential is a single, distinct electrical event. If the channel stayed open, you'd get a continuous influx of sodium, and the electrical signal would just… fizzle out, or worse, become chaotic. We need those clean, crisp action potentials, like perfectly delivered punchlines. Inactivation ensures that each "message" sent down the neuron is a discrete unit of information, not a jumbled mess. It’s like making sure each email you send arrives as a single, coherent message, not a stream of random words. Nobody wants that kind of inbox!

Secondly, and this is where it gets really interesting for how neurons "talk" to each other, inactivation is crucial for the refractory period. Ah, the refractory period! This is that brief period after an action potential where the neuron is less likely, or even completely unable, to fire another one. Think of it as a brief cooldown period for the neuron. During inactivation, the channel is physically blocked and cannot be opened again, no matter how strong the electrical stimulus. It's like the bouncer has put up a velvet rope, and even the most important VIP can't get back in right away. This "resting" or "inactivated" state is essential for ensuring that the electrical signal travels in one direction down the axon, like a one-way street. We don't want traffic jams in our nervous system, do we? That would be a disaster!

So, to recap this fancy inactivation business: the voltage-gated sodium channel opens up, letting the sodium party begin. But then, after a very brief moment, a part of the channel itself swings into place, blocking the pore. This inactivated state prevents further sodium flow, even if the trigger is still there. It's a temporary "closed for business" sign that ensures the action potential is a well-behaved, unidirectional event. It's like the channel is saying, "Had my fun, now I need to recharge my batteries for the next round." And this recharging process is what leads us to the recovery from inactivation. Because, thankfully, this isn't permanent!

The inactivation isn't a permanent "off" switch. It's more like a "pause" button. Eventually, the channel will recover from this inactivated state and return to its original closed state. This recovery process usually involves the 'plug' or 'lid' swinging back out of the way. This recovery can take a little bit of time, and the speed at which it happens is important for determining how quickly the neuron can fire another action potential. Think of it as the channel taking a short nap. After the nap, it’s refreshed and ready to go again. The length of this nap is what dictates how long the neuron has to wait before it can join the next exciting round of action potentials. It’s all about timing, really. Like a perfectly choreographed dance routine.

This whole cycle of opening, inactivating, and then recovering is fundamental to how neurons generate and propagate electrical signals. It’s a beautifully orchestrated molecular dance that keeps our nervous system humming along. Without inactivation, our neurons would be in a constant state of firing, which, as you can imagine, would be pretty chaotic. It's like trying to have a conversation in a room where everyone is shouting at once. Inactivation brings a much-needed order to the electrical chaos. It’s the silent hero of the action potential!

The precise mechanisms of inactivation can get pretty complex, involving specific parts of the sodium channel protein called the inactivation gate. Some channels have faster inactivation than others, which can influence the firing frequency of different types of neurons. It’s like having different types of party guests: some are super enthusiastic and want to dance all night, while others prefer a more controlled rhythm. The inactivation gate is the little molecular gatekeeper that decides when the music has to stop for a bit. And believe me, it’s a very sophisticated gatekeeper!

Think about diseases that affect nerve function, like epilepsy or certain forms of pain. Often, these are linked to problems with ion channels, including their inactivation properties. If the inactivation is too slow, or doesn't happen properly, neurons can become hyperexcitable, firing off too many signals. It's like the party never stops, and eventually, things get out of control. On the flip side, if inactivation is too fast or too strong, it can dampen nerve activity too much, leading to numbness or weakness. So, the delicate balance of opening, inactivation, and recovery is absolutely critical for a healthy nervous system. It's a finely tuned instrument, and when it goes out of tune, things can get a bit… interesting, in a not-so-good way.

So, there you have it! Inactivation of a voltage-gated sodium channel. It's not just a fancy word; it's a vital process that ensures our neurons can communicate effectively and efficiently. It’s the silent partner to the exciting opening of the channel, the crucial step that allows for proper signaling and prevents runaway excitation. It's the sensible part of the neuron's personality, making sure that even during the most exciting electrical events, there's a plan for a sensible pause. It’s like the responsible adult at the party, making sure everyone eventually heads home safely and soundly. And for that, we can all be very grateful. Cheers to inactivation, the unsung hero of the action potential!