Compared To An Uncatalyzed Reaction An Enzyme Catalyzed Reaction

So, picture this: I’m in my tiny apartment kitchen, staring at a jar of instant coffee. My mission? To make a decent cup of joe. Now, I’m not some fancy barista with a souped-up espresso machine. My equipment is… basic. And my patience, well, let’s just say it’s limited on a Monday morning. So, I grab my trusty spoon, dump some of that dark, gritty stuff into a mug, pour in some hot water, and stir. Lots and lots of stirring. It takes a good minute, maybe two, for all that caffeine goodness to even begin to dissolve. It’s a bit of a slow, clunky process, right? Like trying to push a boulder uphill with a toothpick.

And then, just the other day, I was visiting my friend Sarah. Sarah, bless her organized heart, is like a scientist in her own kitchen. She’s got all these fancy gadgets, but the real magic happened when she made me coffee. She didn't use instant. Oh no. She ground fresh beans, used a special pour-over contraption, and then… then she added this tiny little something to the hot water. It wasn't sugar, it wasn't milk. It was… an enzyme. I swear, I blinked, and the coffee was instantly (pun intended, sorry!) ready. The aroma was a hundred times better, the taste was like a hug from a friendly bear, and it all happened in what felt like nanoseconds. My instant coffee struggle suddenly seemed like a quaint, almost embarrassing relic of the past.

That little coffee moment got me thinking. It’s a perfect, albeit slightly caffeinated, analogy for something super important in the world of chemistry: catalyzed versus uncatalyzed reactions. My instant coffee situation? That’s basically an uncatalyzed reaction. It gets the job done, eventually, but it’s slow, inefficient, and frankly, a bit of a drag. Sarah’s magical coffee brew? That’s where the enzyme comes in, turning a sluggish process into something speedy and spectacular. It’s like comparing a snail race to a Formula 1 Grand Prix, wouldn't you agree?

The Slow Grind: Uncatalyzed Reactions

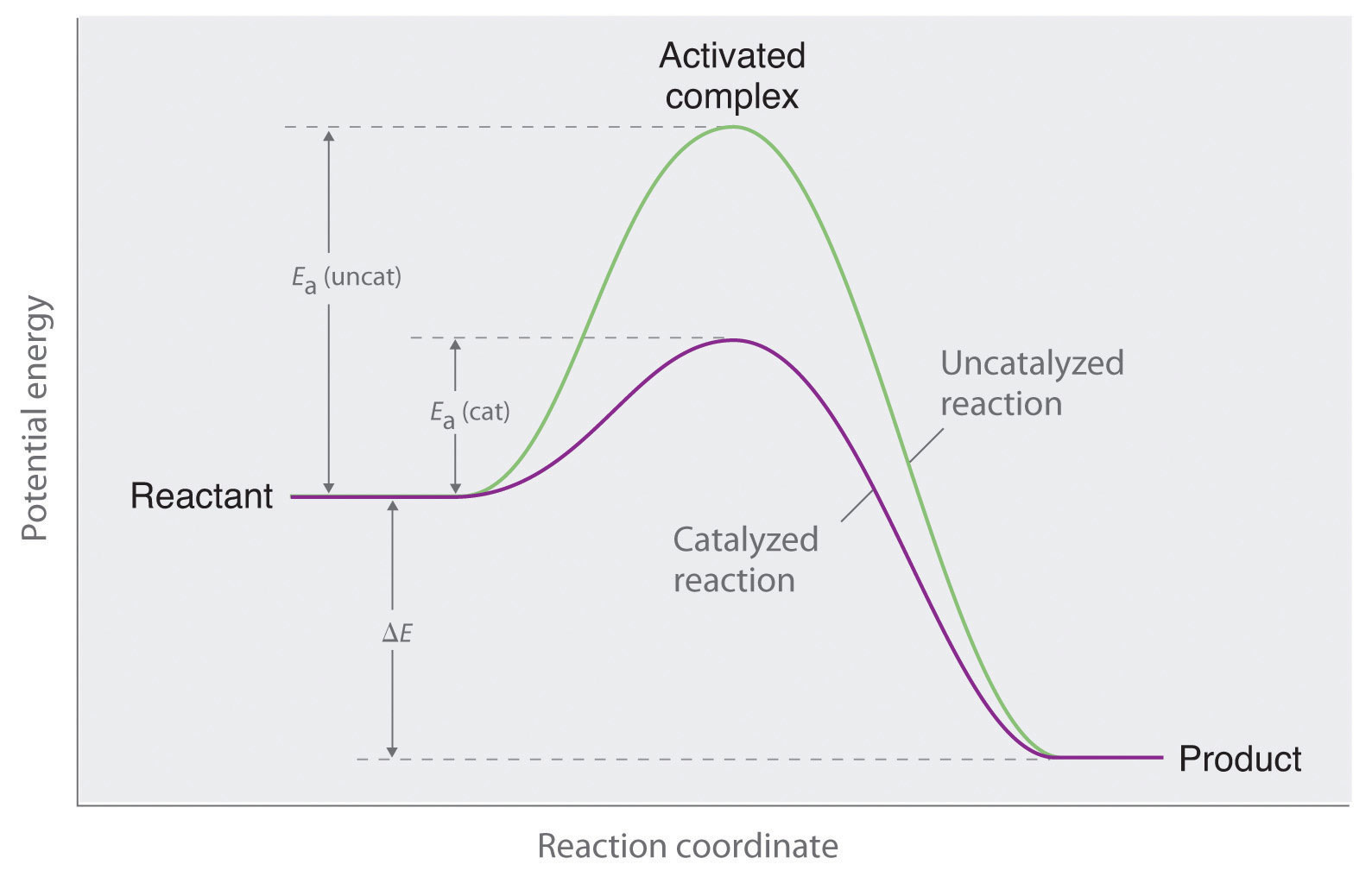

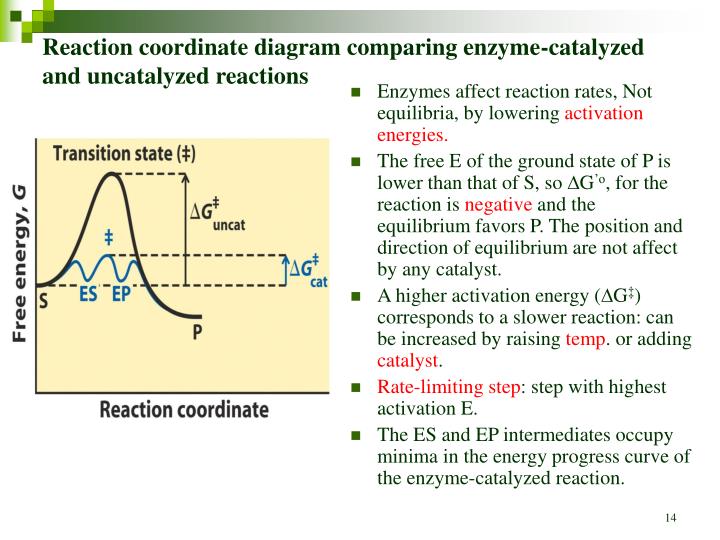

Let’s break down my Monday morning coffee ordeal. When you dump that instant coffee powder into hot water, you're essentially asking the coffee molecules to dissolve into the water molecules. This is a chemical process, and like most chemical processes, it needs a little nudge to get going. Think of it as needing a certain amount of energy to kickstart things. This energy is called the activation energy.

Imagine you have a big pile of LEGO bricks, and you want to build a castle. The activation energy is like the effort you need to put in to pick up that first brick, find the right spot, and start clicking things together. For my instant coffee, the water molecules are bumping into the coffee molecules, trying to pull them apart and dissolve them. But these coffee molecules are pretty happy holding hands with each other, and the water molecules just aren't energetic enough, or in the right orientation, to break those bonds easily. So, you stir, adding more kinetic energy (movement) to the system, hoping to speed up those collisions and increase the chances of a successful dissolution. It’s a lot of random bumping and grinding.

This is the essence of an uncatalyzed reaction. The reaction will happen. Given enough time and the right conditions, your instant coffee will eventually dissolve. But it’s like waiting for a sloth to win a marathon. The rate of reaction is relatively slow because only a small fraction of collisions between reactant molecules have enough energy to overcome the activation energy barrier and lead to a product.

It's like this for a lot of natural processes too. Think about rust forming on a piece of iron. It happens, but it’s not exactly an overnight transformation, is it? Or the breakdown of complex materials in the environment – it can take years, decades, even centuries. These are all reactions chugging along at their own, unhurried pace, without any helpful intervention.

The problem with slow reactions, especially in biological systems, is that life needs to happen fast. Cells don't have eons to wait for essential processes to occur. Imagine if your body's digestive enzymes worked as slowly as my instant coffee dissolving. Breakfast would be a multi-day affair! Seriously, can you imagine?

The Turbo Boost: Enzyme-Catalyzed Reactions

Now, let’s get back to Sarah and her magical coffee. The enzyme she added is like a tiny, highly specialized little helper. In chemistry, a catalyst is a substance that increases the rate of a chemical reaction without itself undergoing any permanent chemical change. It’s like a helpful guide who knows the shortcuts and makes the journey much smoother.

Enzymes are a special class of biological catalysts. They are typically proteins, and they are incredibly efficient and specific. Think of them as molecular machines, each designed to perform a very particular task. In Sarah's coffee situation (and I'm simplifying here, as coffee making is complex!), the enzyme was likely helping to break down certain compounds in the coffee grounds more quickly, making them more soluble in water.

The magic of an enzyme lies in its ability to lower the activation energy of a reaction. Remember that LEGO castle analogy? Instead of needing to lift and place each brick with immense effort, the enzyme provides a scaffold, or a series of steps, that makes it much easier to assemble the castle. It's like the enzyme says, "Hey, instead of trying to smash these coffee molecules apart with brute force, let's just gently coax them into dissolving. I've got a special pocket here that fits them perfectly!"

This specific fitting is key. Enzymes have what’s called an active site. This is a small region on the enzyme where the reactant molecules, called substrates, bind. The shape and chemical properties of the active site are perfectly complementary to the substrate, like a lock and key. When the substrate binds to the active site, the enzyme can then facilitate the chemical transformation, either by straining the bonds within the substrate, bringing reacting molecules closer together, or providing a favorable chemical environment.

Once the reaction is complete, the products are released from the active site, and the enzyme is free to bind to another substrate molecule and repeat the process. This is why enzymes are so effective – they can participate in thousands, even millions, of reactions per minute! It’s an astounding level of efficiency. And it all happens without the enzyme itself being used up. Pretty neat, huh?

Speed Demons and Slowpokes: The Rate Difference

The most striking difference between an uncatalyzed reaction and an enzyme-catalyzed reaction is the rate. And when I say rate, I mean how fast the reaction happens. My instant coffee, even with vigorous stirring, takes a good couple of minutes to become drinkable. This is a relatively slow rate for a simple dissolution. Sarah's enzyme-assisted coffee? It was ready almost instantly. This isn't just a small improvement; it can be a difference of orders of magnitude – meaning thousands, millions, or even billions of times faster!

Think about digestion. When you eat food, your body needs to break down complex carbohydrates, proteins, and fats into smaller molecules that can be absorbed. This process, if left to the uncatalyzed reactions of your stomach’s environment, would take an incredibly long time. Fortunately, your body is packed with enzymes – amylase for carbohydrates, proteases for proteins, lipases for fats – all working tirelessly to speed up these essential breakdown reactions. Without them, you'd basically starve to death while still digesting your lunch!

The activation energy barrier is the culprit behind the slowness of uncatalyzed reactions. It's the energy hurdle that molecules must clear to react. By lowering this barrier, enzymes make it much easier for the reaction to proceed. More molecules will have enough energy to react at any given moment, leading to a dramatic increase in the reaction rate.

It’s like trying to get a group of people to climb a very steep hill. In an uncatalyzed scenario, most people will get tired and turn back. But if you build a series of gentle ramps and stairs (the enzyme), suddenly almost everyone can make it to the top with ease and much faster. The energy required for each step is significantly reduced.

Specificity: The Picky Eaters of the Chemical World

Another crucial difference, and something that fascinates me about enzymes, is their specificity. My instant coffee powder dissolves in hot water. It also dissolves, albeit slower, in room temperature water. It might even dissolve a tiny bit in cold water, but it would take ages. It’s pretty indiscriminate about the solvent, as long as it’s a liquid. But enzymes? They are incredibly picky eaters.

An enzyme is designed to catalyze a specific reaction, or a very small group of related reactions. This is because its active site has a very precise three-dimensional shape that only fits a particular substrate, or a set of very similar substrates. This is the "lock and key" model I mentioned earlier. If the shape doesn't match, the substrate won't bind effectively, and the reaction won't be catalyzed. It's like trying to use a car key to open your house door – it just won't work, no matter how hard you try!

This specificity is absolutely vital for life. Our cells are incredibly crowded environments with thousands of different molecules. If enzymes weren't specific, they could accidentally catalyze the wrong reactions, leading to chaos and cellular dysfunction. Imagine if the enzyme that breaks down sugar in your body also decided to break down your DNA! Not a good situation.

This specificity allows for incredibly complex biochemical pathways to operate within a cell. Each enzyme plays its part in a precise sequence, ensuring that molecules are processed in the correct order and converted into the right products. It’s a marvel of biological engineering.

Conditions Matter: Environment and Enzyme Function

While both catalyzed and uncatalyzed reactions are affected by their environment, the impact on enzyme-catalyzed reactions is far more pronounced. Enzymes are sensitive little things. They have optimal conditions under which they function best, and deviating from these conditions can significantly impair or even destroy their activity.

Temperature is a big one. For uncatalyzed reactions, generally, increasing temperature increases the reaction rate because molecules move faster and collide more often with greater energy. However, for enzymes, this isn't quite so simple. Up to a certain point, increasing temperature will increase enzyme activity. But beyond their optimal temperature, enzymes begin to denature. This means their delicate protein structure unfolds and loses its shape, including the active site. Once denatured, an enzyme loses its catalytic ability. So, while boiling water might dissolve my instant coffee faster, it would utterly destroy any enzyme you might try to add!

Similarly, pH is crucial for enzyme function. Enzymes have an optimal pH range. If the environment becomes too acidic or too alkaline for a particular enzyme, it can also denature or alter its shape, rendering it inactive. Think about the enzymes in your stomach, which operate in a highly acidic environment, compared to the enzymes in your small intestine, which work best in a more neutral or slightly alkaline environment. This is why our bodies have different digestive compartments with carefully controlled pH levels.

Uncatalyzed reactions are generally less sensitive to these fluctuations. While temperature and pressure can still affect them, they don't usually have a specific structural requirement that can be so easily disrupted.

The Big Picture: Why Enzymes Are Everything

So, when we compare an uncatalyzed reaction to an enzyme-catalyzed reaction, the differences are profound. It’s not just about speed; it’s about efficiency, specificity, and the very possibility of life as we know it. Without enzymes, our cells wouldn't be able to perform the countless chemical reactions necessary for everything from breathing and digesting to thinking and moving.

My instant coffee analogy, while lighthearted, really does highlight this fundamental difference. My slow, clunky stirring is the uncatalyzed world – functional, but inefficient. Sarah's coffee, made with a tiny helper, represents the enzyme-catalyzed world – fast, precise, and elegant. It’s the difference between a caveman trying to start a fire by rubbing two sticks together for hours (uncatalyzed) and using a modern lighter (catalyzed). Both can produce fire, but the latter is infinitely more practical and controlled.

From the simplest single-celled organisms to the most complex multicellular beings, enzymes are the unsung heroes of biochemistry. They are the molecular gears that keep the engine of life running smoothly. They allow for complex processes to occur under mild conditions (like body temperature and pH), something that would require extreme heat, pressure, or harsh chemicals in an uncatalyzed system.

Next time you enjoy a meal, or take a deep breath, or even just digest your morning coffee, take a moment to appreciate the incredible work of enzymes. They are the catalysts that transform the potentially sluggish and chaotic world of chemistry into the vibrant, dynamic, and absolutely essential processes of life. They are truly nature's tiny, super-powered helpers. And I, for one, am incredibly grateful for them, especially on those Monday mornings.