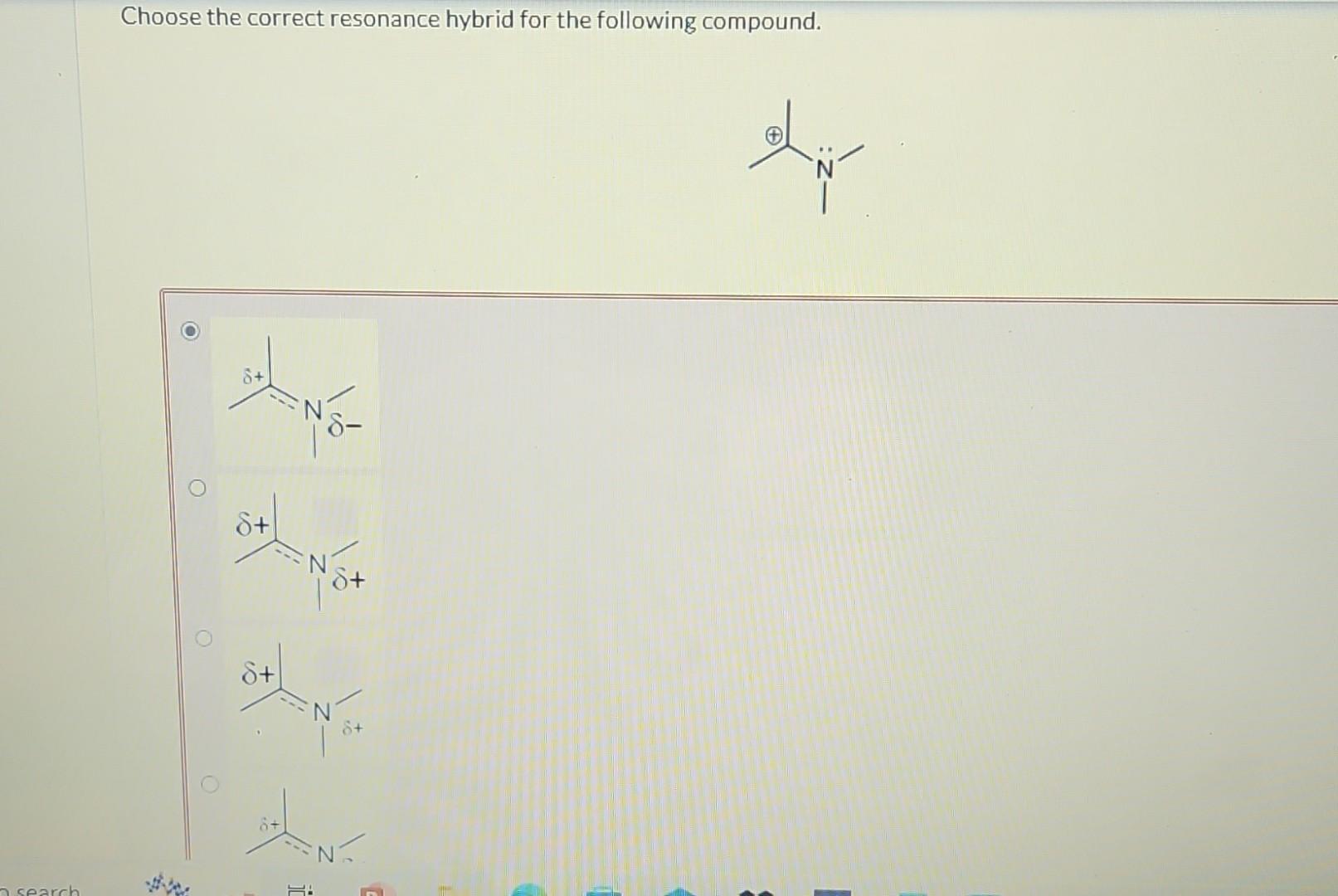

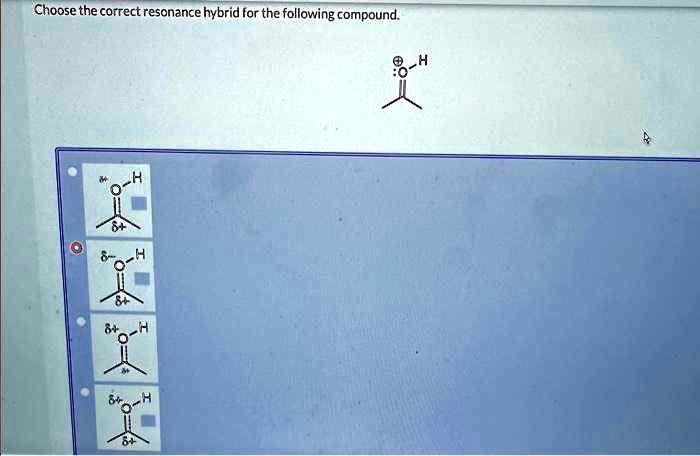

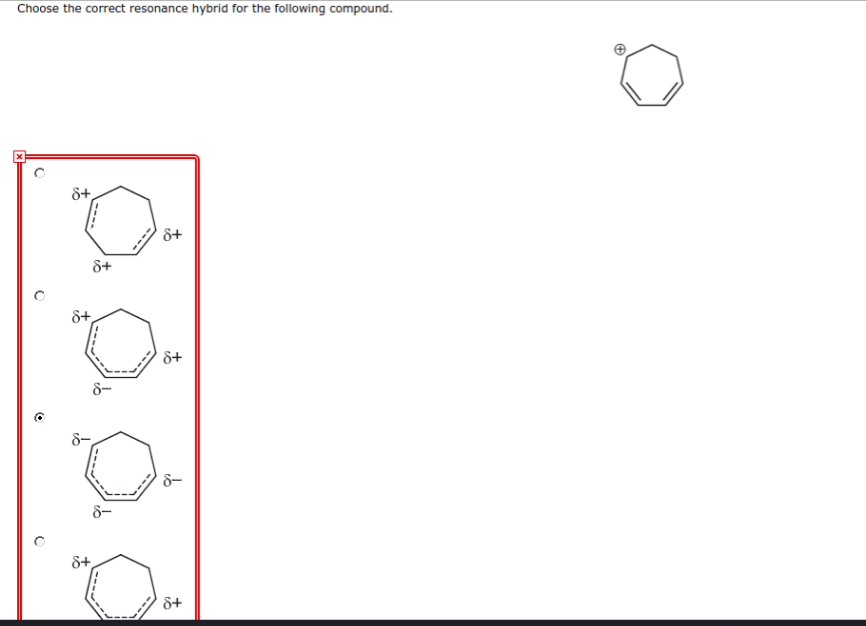

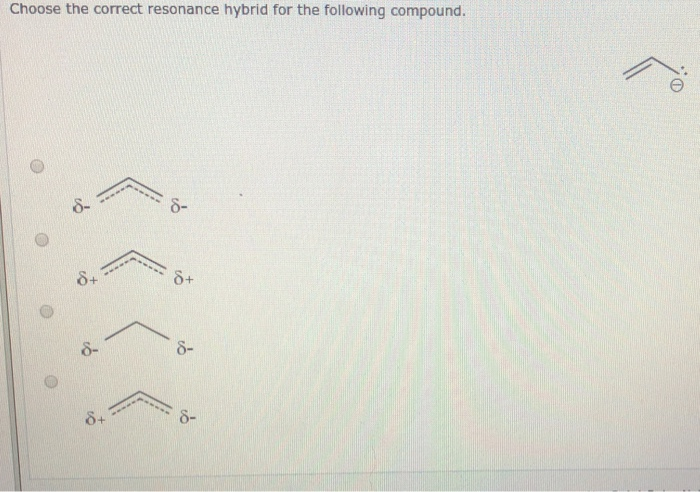

Choose The Correct Resonance Hybrid For The Following Compound.

Okay, so picture this: I'm in my first-ever organic chemistry lecture. The professor, bless his tweed-wearing heart, is droning on about molecules. Suddenly, he projects this image on the screen – a molecule that looks… well, a bit like it’s having an identity crisis. He calls it a “resonance hybrid.” My brain, at that point, was pretty much just trying to remember what an atom was, let alone a hybrid of something. I remember nudging my friend and whispering, “Is that molecule… broken?” She just rolled her eyes. Little did I know, that seemingly “broken” molecule was going to be a recurring theme in my chem life, and understanding its true nature would be the key to unlocking a whole bunch of cool stuff.

And that’s exactly what we’re diving into today! We’re going to unravel the mystery of the resonance hybrid. Think of it as figuring out the real personality of someone who’s a little bit of everything. You know, like that friend who can be super chill one minute and a total party animal the next? That’s kinda what resonance is all about, but for atoms and electrons. It’s not about switching between personalities, but about a blend of them all being present simultaneously.

So, if you’ve ever seen a molecule that looks like it’s trying on different outfits, and you’ve felt a tiny bit bewildered (like yours truly that first day), then you’re in the right place. We're going to learn how to pick the correct resonance hybrid. It’s like being a detective, but instead of clues, we’re looking at electron movement and stability. Pretty neat, right?

Let’s get down to brass tacks. What exactly is resonance? In the simplest terms, resonance occurs when a molecule, or a polyatomic ion, cannot be adequately represented by a single Lewis structure. Instead, it’s best described as an average of two or more contributing structures, called resonance structures or contributing structures. These aren’t real, separate molecules bouncing around; they are just our attempts to draw what’s actually happening.

Imagine you have a really shy cat. You could draw a picture of it hiding under the bed (one resonance structure), or a picture of it peeking out with one eye (another resonance structure). But the real cat is neither of those exclusively. It’s somewhere in between, a blend of shy and curious. The resonance hybrid is that actual cat, the truest representation, which is more stable than either of the individual drawings could ever be.

This concept is super important because it directly impacts a molecule's stability, its bond lengths, and its reactivity. Molecules that exhibit resonance are generally more stable than their non-resonant counterparts. Why? Because the electrons are delocalized, meaning they aren’t stuck in one spot between two atoms. They’re spread out over a larger area, which is a much happier and more stable arrangement for them. Think of it like sharing is caring, but for electrons!

Now, here’s the million-dollar question: how do we draw these contributing structures, and more importantly, how do we figure out which ones are the most important? That’s where the real magic (and the potential for confusion) happens. We use what are called curved arrows to show the movement of electrons. These arrows are like little messengers, telling us where an electron pair is moving from and to. They always show the movement of a pair of electrons, either a lone pair or a pi bond electron pair.

We only move electrons; we never move atoms. This is a cardinal rule, folks. If you find yourself moving an atom with a curved arrow, pause. Take a deep breath. And go back to the drawing board, literally. It’s a common beginner’s mistake, so don’t beat yourself up if you do it. We’ve all been there.

There are a few common patterns for electron movement that lead to resonance structures. One of the most frequent involves a pi bond adjacent to a lone pair. The pi bond electrons can move to form a new pi bond with an adjacent atom, or a lone pair can move to form a pi bond.

Another common pattern is a pi bond next to a positive charge. Here, the pi bond can break, and its electrons can move to form a new bond to the positively charged atom, neutralizing it. Or, you might see a pi bond next to a negative charge, where the negative charge can move to form a new pi bond.

And then there's the pi bond next to a radical (an unpaired electron). Similar to charges, the pi bond electrons can rearrange to accommodate the unpaired electron.

So, the process usually goes like this: you have a starting Lewis structure. You identify a spot where electrons can move according to these patterns. You draw your curved arrows to show that movement. Then, you redraw the molecule with the new electron arrangement and recalculate formal charges. This new drawing is a resonance structure. You repeat this process to find all possible valid resonance structures.

But here’s the kicker: not all resonance structures are created equal. Some contribute more to the overall hybrid than others. This is where we start talking about resonance contributors or major/minor resonance structures. We have rules, or guidelines, to help us determine this.

First off, the more covalent bonds a structure has, the more stable it is. Simple enough, right? More bonds generally mean a more complete octet for more atoms, which is a good thing in the world of chemistry.

Secondly, structures with fewer formal charges are more stable. Formal charge is a way to assign a charge to an atom in a molecule, assuming all bonds are purely covalent and electrons are shared equally. Ideally, we want formal charges to be as close to zero as possible. So, if one structure has a +1 and a -1 charge, and another has no charges, the second one is usually much better.

Third, if formal charges are present, structures where the negative charge is on a more electronegative atom (like oxygen or fluorine) and the positive charge is on a less electronegative atom (like carbon) are more stable. Nature likes negative charges to be cozy with electron-loving atoms. Think of it as finding the right home for your charges!

And finally, structures with a complete octet on more atoms are more stable. Remember those octet rules we learned? Yeah, they’re still super important here. Atoms generally want eight electrons in their valence shell. If a structure has an atom with only six electrons, it’s going to be pretty unhappy and less stable.

The resonance hybrid is the average of all these contributing structures, weighted by their stability. The major resonance contributors, the ones that are more stable, have a larger say in what the hybrid looks like. The minor contributors have less influence.

So, let’s say we’re given a compound and asked to choose the correct resonance hybrid. This usually means we’re being asked to identify the most stable contributing structure, or sometimes, to draw the hybrid itself, which will be a blend of the major contributors.

Let’s work through a hypothetical example. Suppose we’re looking at the acetate ion, CH₃COO⁻. We can draw a few Lewis structures for it. One might have the negative charge on one oxygen, and the double bond on the other. Another might swap those around. Let’s call these Structure A and Structure B.

In Structure A, we have a C=O double bond and a C-O⁻ single bond. In Structure B, we have the C-O single bond and the C=O⁻ double bond. Both oxygens have complete octets. Both structures have one oxygen with a formal charge of -1 and another with a formal charge of 0 (from the double bond). The carbons all have complete octets.

Are there any differences in stability? Not really, according to our rules. The negative charge is on an oxygen in both, and the octets are full. So, both Structure A and Structure B are equally good resonance contributors. They are both major resonance structures. The resonance hybrid would then be a blend of these two, where the negative charge is delocalized equally over both oxygen atoms, and the C-O bonds are intermediate in length between a single and a double bond.

Now, what if we were presented with a few options for the resonance hybrid, and we had to pick the right one? This is where the real test comes in. Let’s imagine we’re looking at the carbonate ion (CO₃²⁻). We can draw three resonance structures, each with one C=O double bond and two C-O single bonds, with the negative charges on the single-bonded oxygens.

The three structures are essentially identical in terms of stability: negative charge spread over three oxygens, complete octets on all atoms. The hybrid would show partial double bond character for all three C-O bonds and a -2/3 charge on each oxygen.

But what if the options presented were: a) A structure with one C=O double bond and two C-O single bonds, with the double bond on oxygen that has a formal charge of -1. b) A structure with three C-O single bonds and all oxygens having a formal charge of -2/3. c) A structure with one C=O double bond and two C-O single bonds, with the double bond on oxygen that has a formal charge of 0.

Let’s break this down. Option (a) is incorrect because the negative charge should be on the single-bonded oxygens, not the doubly bonded one. Option (b) is the idealized resonance hybrid representation, showing delocalization. Option (c) is also incorrect for the same reason as (a).

However, the question asks to "Choose The Correct Resonance Hybrid". Often, when given multiple-choice options, they're asking for the most stable contributing structure that represents the essence of the hybrid, or a representation that accurately depicts the electron distribution. In the case of carbonate, any of the three major contributors would be considered "correct" representations if presented individually. If option (b) were presented, it would be the most accurate depiction of the hybrid itself, showing the average electron distribution.

The key is to apply those stability rules rigorously. Let’s try another one. Consider the allyl cation: CH₂=CH-CH₂⁺. Possible resonance structures are: 1. CH₂=CH-CH₂⁺ 2. ⁺CH₂-CH=CH₂ Let’s analyze these:

Structure 1: A double bond between C1 and C2, a single bond between C2 and C3. C3 has a positive charge. All carbons have full octets except for C3, which has only 6 valence electrons.

Structure 2: A single bond between C1 and C2, a double bond between C2 and C3. C1 has a positive charge. All carbons have full octets except for C1, which has only 6 valence electrons.

Are they equivalent? Yes, in terms of formal charges and electron deficiency. The positive charge is on a terminal carbon in both cases. The double bond is between the other two carbons. The major difference is which terminal carbon holds the charge. These are equally stable, and the hybrid is a blend, with the positive charge delocalized over both terminal carbons and a partial double bond character between C1-C2 and C2-C3. If given options, we'd look for representations that reflect this delocalization, or the individual contributing structures.

But what if you were presented with something like this for the allyl cation:

a) CH₂⁻-CH=CH₂

b) CH₂=CH-CH₂⁻

c) CH₂=CH-CH₂⁺

d) CH₂⁺-CH=CH₂

Here, we need to be super careful. Options (a) and (b) represent the allyl anion, not the allyl cation. They have a negative charge. Option (c) is one valid resonance structure for the allyl cation. Option (d) is the other valid resonance structure for the allyl cation. If the question is "Choose the correct resonance hybrid representation", and we only have single structures as options, it can be a bit ambiguous. However, it's often implied that you're choosing the most stable contributing structure(s) that would make up the hybrid.

In this case, both (c) and (d) are equally valid contributing structures. If the question were phrased as "Which of the following represents a resonance structure of the allyl cation?", then both (c) and (d) would be correct. If it asks for the "correct resonance hybrid", and provides contributing structures as options, it's usually looking for the ones that are most representative. In this scenario, it's highly likely they want you to identify that the charge is delocalized. So, if the options included a representation showing the delocalized charge (like partial charges on both terminal carbons), that would be the best answer. But since we're dealing with single structures, and (c) and (d) are the only valid contributors to the allyl cation hybrid, then either could be considered the "correct" choice depending on how the question is framed and what other options are available.

Let’s refine. When you’re asked to choose the “correct resonance hybrid,” you’re typically being tested on your ability to: 1. Draw valid resonance structures using curved arrows. 2. Identify the most stable resonance structures. 3. Understand that the hybrid is an average of these structures, with major contributors having more influence.

So, if you are given a compound and several potential resonance structures, your job is to evaluate each potential structure against the rules of stability. You’ll be looking for the ones that obey the octet rule as much as possible, minimize formal charges, and place charges on appropriate atoms.

Consider benzene (C₆H₆). It’s famous for its resonance. We can draw two primary Lewis structures, where the double bonds alternate around the ring. These two structures are identical in stability. The resonance hybrid of benzene is a ring with all C-C bonds being identical, somewhere between a single and a double bond, and the pi electrons are delocalized over the entire ring. If presented with options, you'd look for a representation that shows this delocalization, perhaps with a circle inside the hexagon, or a depiction where all C-C bonds are shown as equivalent with partial double bond character.

If you were given options for benzene like: a) A Kekulé structure with alternating double and single bonds. b) A hexagon with a circle inside. c) A structure with all C-C bonds shown as equal with partial double bond character. d) All of the above.

In this case, (a) are the resonance contributors, and (b) and (c) are representations of the resonance hybrid. So, (d) would be the most comprehensive and correct answer, acknowledging both the contributors and the hybrid representation.

The trickiest part is often when the "correct" option isn't a perfect hybrid representation but the most significant contributing structure. You need to be able to rank the stability of different Lewis structures for the same molecule. Remember the hierarchy: 1. Maximize octets. 2. Minimize formal charges. 3. Negative charge on electronegative atom, positive charge on electropositive atom. 4. Distribute charges as evenly as possible.

So, if you're given a molecule and asked to choose its correct resonance hybrid, and the options are various Lewis structures, you’re essentially being asked to pick the most stable Lewis structure(s) that contribute to the hybrid. The hybrid itself is a theoretical construct, an average, but its nature is dictated by the stability of its contributors.

Don't get discouraged if it takes a few tries to get the hang of drawing resonance structures and assessing their stability. It’s a skill that develops with practice. Think of it like learning to ride a bike. You wobble, you might fall, but eventually, you get steady and can navigate those electron highways like a pro. The key is to keep drawing, keep evaluating, and keep thinking about what makes electrons happy. Because in the end, that’s what resonance is all about: finding the most stable, happiest electron arrangement for a molecule.

So next time you see a molecule that looks like it's in flux, don't call it broken. Call it resonant! And know that you have the tools to figure out its true, averaged-out, super-stable personality. Happy electron shuffling!