Calculate The Standard Enthalpy Change For The Reaction 2al+fe2o3

Ever looked at your rusty old bike chain and wondered, "What's the deal with all this oxidation?" Or maybe you've seen those dramatic thermite reaction videos online, the ones where molten metal practically leaps out of the container? Today, we're diving into a similar, albeit slightly less fiery, chemical showdown. Think of it as the ultimate showdown between a grumpy, old metal oxide and a sprightly, eager metal. We're talking about calculating the standard enthalpy change for the reaction between aluminum (Al) and iron(III) oxide (Fe₂O₃). Don't let the fancy words scare you; it's actually as straightforward as figuring out if you have enough snacks for movie night.

You know how sometimes you're trying to make a sandwich, and you've got all the ingredients, but something just doesn't quite come together? Maybe you forgot the mustard, or the bread is a little stale. Chemical reactions are a bit like that. They involve bringing things together (reactants) and seeing what you get (products). And just like how some cooking experiments can either turn into a culinary masterpiece or a smoke alarm symphony, chemical reactions release or absorb energy. That energy difference is what we call enthalpy change. Today, we're calculating the standard enthalpy change, which is basically the energy change when everything is happening under ideal, "chef's kiss" conditions – like a perfectly seasoned kitchen.

So, our players in this chemical drama are aluminum (Al), that shiny, lightweight metal we see in soda cans and foil. And on the other side, we have iron(III) oxide (Fe₂O₃). This guy is essentially rust, that flaky, reddish-brown stuff that makes you want to whisper sweet nothings of WD-40 to your garden tools. It's like the grumpy old uncle of iron, all bundled up and not wanting to play nice.

The reaction itself looks like this: 2Al + Fe₂O₃ → Al₂O₃ + 2Fe. In plain English, aluminum is saying, "Hey, iron oxide, you look a little… retired. How about I take that oxygen you've been holding onto, and you can just be plain old iron again?" And guess what? Aluminum is a pretty determined metal. It's got a real thing for oxygen. It’s like a kid who’s just discovered a new favorite toy and absolutely has to have it.

Now, why would we care about this particular reaction? Well, the thermite reaction, which is a supercharged version of this, is famous for producing tons of heat. We're talking enough heat to melt steel! It's used in things like welding railway tracks – imagine patching up your train tracks with the power of a dragon's sneeze! Even though our "standard" calculation isn't about creating a volcanic eruption, understanding the energy involved helps us predict how much heat will be released (or absorbed, though in this case, it’s definitely released – we're talking a nice, warm chemical hug).

To calculate this standard enthalpy change, we need some specific numbers, like ingredients for a recipe. These numbers are called standard enthalpies of formation (ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3>). Think of these as the "pre-built energy cost" of making each compound from its fundamental elements in their most stable form. It's like knowing how much effort it takes to bake a cake from scratch versus buying one from the store. Some things are inherently more "energetically expensive" to create than others.

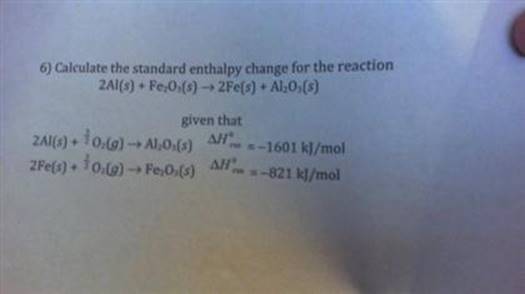

We find these handy-dandy numbers in tables, like a cheat sheet for chemists. For our reaction, we'll need:

- The standard enthalpy of formation for Fe₂O₃.

- The standard enthalpy of formation for Al₂O₃.

Now, here's a neat little trick: the standard enthalpy of formation for elements in their most stable form (like pure aluminum metal, Al, or pure iron metal, Fe) is zero. Why? Because it takes no extra energy to "form" something that already exists in its most basic, happy-go-lucky state. It's like saying the "energy cost" of being aluminum is zero, because it's just… aluminum. No fuss, no muss.

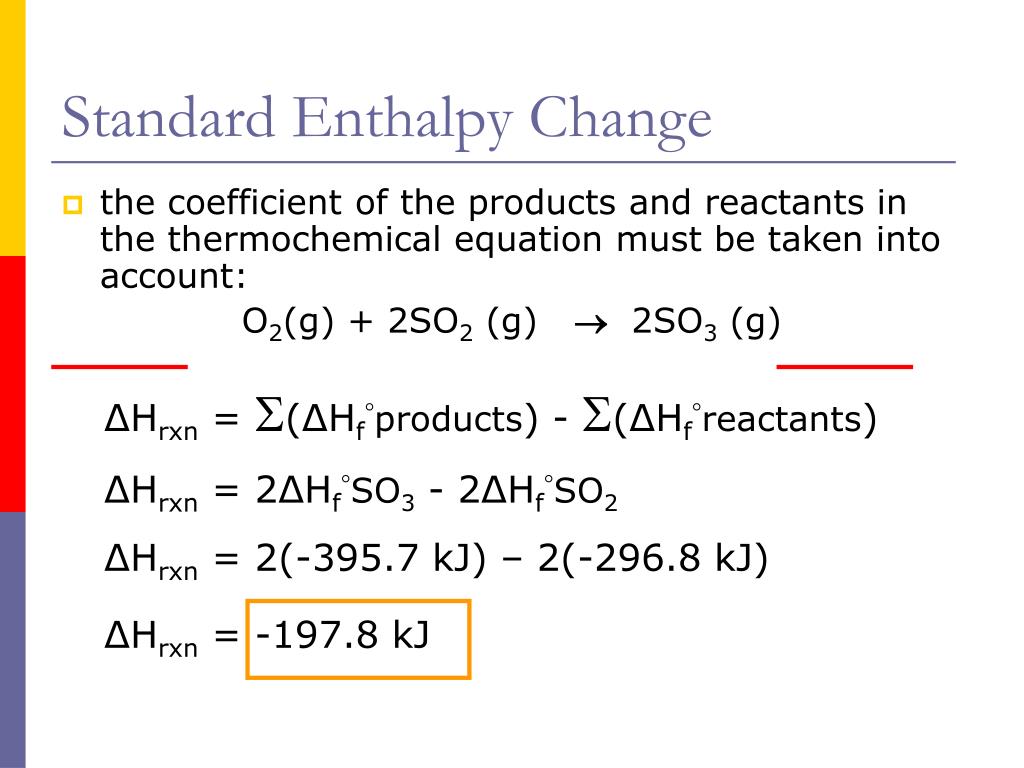

Our formula for calculating the standard enthalpy change of a reaction (ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3>ₓ<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3>ⁿ) is pretty straightforward. It’s basically: (sum of enthalpies of formation of products) - (sum of enthalpies of formation of reactants).

So, let's break it down. Our products are Al₂O₃ and 2Fe. Our reactants are 2Al and Fe₂O₃.

The equation looks like this:

ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3>ₓ<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3>ⁿ = [ (1 × ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3> of Al₂O₃) + (2 × ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3> of Fe) ] - [ (2 × ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3> of Al) + (1 × ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3> of Fe₂O₃) ]

Remember, the ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3> for Al and Fe are both zero, because they are elements in their standard states. So, those terms conveniently disappear, like that one sock that always goes missing in the laundry. Poof!

This simplifies our equation to:

ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3>ₓ<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3>ⁿ = [ (1 × ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3> of Al₂O₃) ] - [ (1 × ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3> of Fe₂O₃) ]

Now, we need our actual numbers. These are generally found in chemistry textbooks or reliable online resources. Let's plug in some commonly accepted values (remember, these can vary slightly depending on the source, so treat them as good estimates, like guessing the number of jellybeans in a jar).

Typical values are:

- ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3> of Al₂O₃ is approximately -1675.7 kJ/mol. The negative sign tells us this compound is quite stable, and it released energy when it was formed. It’s like a well-rested, calm person.

- ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3> of Fe₂O₃ is approximately -824.2 kJ/mol. This one is also stable, but not as much as aluminum oxide. It's like someone who's had a decent night's sleep, but maybe had a weird dream.

Let's pop these into our simplified equation:

ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3>ₓ<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3>ⁿ = [ 1 × (-1675.7 kJ/mol) ] - [ 1 × (-824.2 kJ/mol) ]

Now, let's do some simple math, like figuring out how much change you should get back from buying a pizza. We have a negative number minus a negative number, which is the same as adding a positive number. So:

+for+the+reaction.jpg)

ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3>ₓ<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3>ⁿ = -1675.7 kJ/mol + 824.2 kJ/mol

And the result is:

ΔH°<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3>ₓ<0xE1><0xB5><0xA3>ⁿ = -851.5 kJ/mol

So, what does this big negative number mean? It means the reaction is exothermic. That's a fancy way of saying it releases heat. It's like when you're trying to start a campfire and you get that initial burst of warmth – this reaction gives off a significant amount of energy. It's not quite the raging inferno of a full-blown thermite reaction, but it's definitely a warm chemical hug, maybe even a slightly too enthusiastic one.

Imagine you’re trying to get your kids to clean their room. You can either bribe them (absorbing energy, endothermic) or they can get so excited about a new game that they miraculously clean it themselves to get to it faster (releasing energy, exothermic). Our aluminum and iron oxide are definitely in the "excited to get to the new game" category.

The value of -851.5 kJ/mol tells us that for every mole of Fe₂O₃ that reacts with 2 moles of Al, approximately 851.5 kilojoules of energy are released into the surroundings. That's a fair chunk of energy, enough to feel the warmth, and in a more concentrated form, enough to make things glow!

It’s fascinating to think about how these numbers, which seem so abstract, have real-world implications. They help engineers design everything from safer batteries to more efficient industrial processes. They even help us understand why your old garden rake looks like it’s about to crumble into dust.

So, next time you see rust, or think about those amazing thermite welding videos, you can remember this little chemical equation and the energy that’s hiding behind it. It’s just a bunch of atoms deciding to rearrange themselves, and in doing so, they either warm us up or cool us down. And our aluminum and iron(III) oxide reaction? It's definitely bringing the warmth to the party!

It’s like a chemical trade-off. Aluminum is saying, "I'll take that oxygen, and here’s some heat as a thank you gift!" And iron is happy to shed its oxide coat and just be plain old iron again. Everyone wins, especially our wallets if we're talking about energy savings in industrial applications.

The process of calculating the standard enthalpy change is a fundamental concept in chemistry, a bit like learning your multiplication tables. Once you know the formula and where to find your numbers, you can tackle all sorts of chemical reactions. It’s not about memorizing every single reaction's energy profile, but understanding the method. It's like knowing how to read a recipe, even if you’ve never made that specific dish before.

And this specific reaction, the reaction between aluminum and iron(III) oxide, is a classic for a reason. It’s a great example of a highly exothermic process that’s both scientifically interesting and has practical applications. It's the kind of reaction that makes you say, "Wow, chemistry is pretty cool!" even if you’re not quite ready to start welding train tracks in your backyard.

So there you have it. We've taken a potentially intimidating topic, broken it down with some everyday analogies, and arrived at a neat little number that tells us how much heat this chemical reaction is willing to share. It’s a reminder that even in the seemingly complex world of chemistry, there’s often a simple, logical explanation, and a little bit of heat to go along with it.