Calculate The Energy Of The Photon Emitted For Transition A

So, picture this: I was down at the local science museum the other day, you know, pretending to be a grown-up and all that. And there was this exhibit about light. Super cool stuff, actually. They had these glass tubes filled with different gases, and when you zapped them with electricity, they’d glow with these vibrant, distinct colours. Like, neon signs on steroids. I remember looking at the argon tube, which was this amazing royal purple, and thinking, "Huh. Where does that specific colour come from? Is it like paint? Did they just… choose that purple?"

Little did I know, I was staring at a microscopic light show happening at the atomic level. And the whole question of why that argon glowed purple, and why that purple and not, say, electric blue or sickly green, is the gateway to understanding something pretty mind-blowing: the energy of a photon emitted during a transition. Sounds fancy, I know, but stick with me. It’s actually way less intimidating than it sounds. Think of it as unlocking the secret handshake of light particles.

This whole journey started because I was trying to help my nephew with his homework. He’s at that age where science starts getting a bit more… abstract. We were looking at some diagrams of atoms, with electrons buzzing around the nucleus like tiny, hyperactive bees. And there were these arrows, showing electrons jumping from one energy level to another. My nephew, bless his cotton socks, just looked at me with that classic "what are you even talking about?" expression. So, I figured, if he needs a crash course, chances are some of you out there might too. Because, let’s be honest, who didn’t stare blankly at a physics textbook at some point? Just me? Okay, cool.

Anyway, the core idea here is that electrons in an atom aren't just randomly flitting about. They exist in specific energy levels, like rungs on a ladder. They can’t just hover between the rungs, you know? It’s either on one or the other. These energy levels are quantized, which is a big word that basically means they come in fixed, discrete amounts. Imagine a vending machine: you can’t put in half a dollar coin and get a snack. It has to be a whole coin, or a specific combination of whole coins. Electrons and energy levels are kind of like that. They’re picky eaters, demanding specific energy packets.

Now, when an electron gets excited – maybe by absorbing some energy from heat, or electricity, or even another photon of light – it can jump up to a higher energy level. Think of it like giving that hyperactive bee a little nudge. It’s now in a more energetic, less stable state. It’s like a kid after way too much birthday cake. They’re buzzing with energy, but they’re also kinda on the verge of a meltdown.

And, just like that kid eventually crashes from the sugar high, an electron in an excited state doesn't stay there forever. It wants to get back to its comfy, stable, lower energy level. It needs to shed that extra energy it picked up. So, what does it do? It releases it in the form of a photon. And this photon, my friends, is a tiny little packet of light. It carries away the exact amount of energy that the electron lost when it dropped back down.

This is where the colour comes in. Different colours of light correspond to different amounts of energy. Red light is lower energy, while blue and violet light are higher energy. So, if an electron drops from a high energy level to a slightly lower one, it might emit a low-energy photon, which we see as red. If it drops from a much higher level to a low one, it emits a higher-energy photon, which we see as blue or violet. It’s like the atom is sending out a signal, and the colour of that signal tells us how much energy it just got rid of.

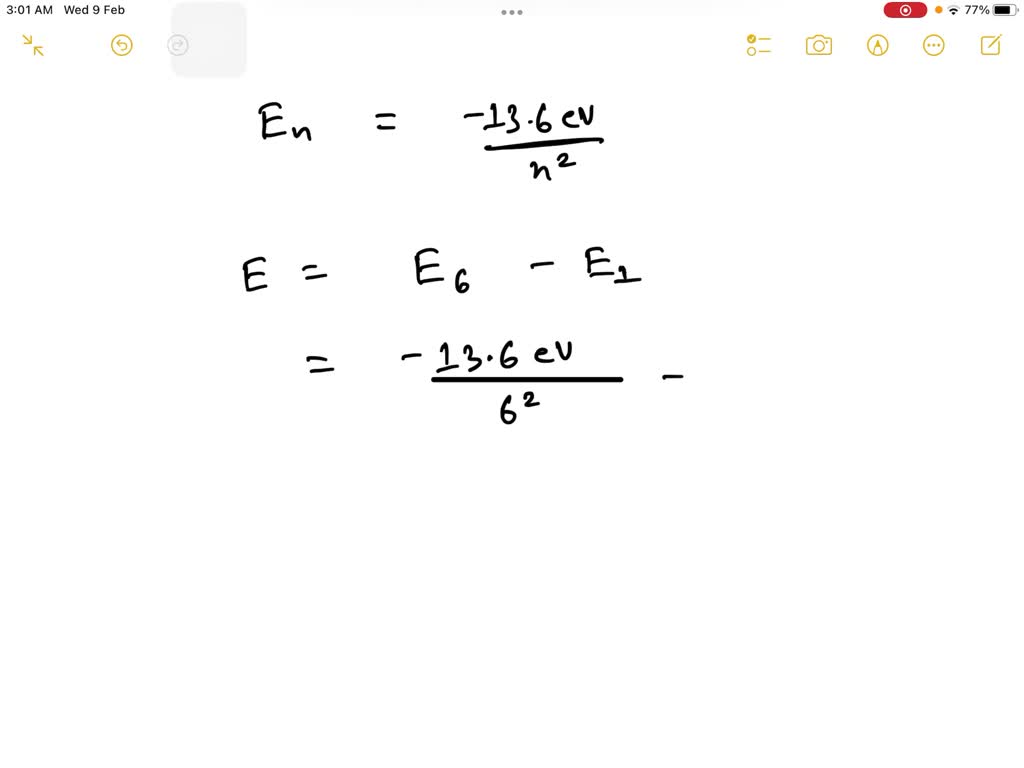

So, how do we actually calculate the energy of this emitted photon? This is where the main event, the calculation part, comes in. We need a couple of key pieces of information. First, we need to know the energy of the initial higher energy level (let’s call this E_initial) and the energy of the final lower energy level (let’s call this E_final). These energy levels are specific to each element, like a fingerprint. They’re usually given in units like electronvolts (eV) or joules (J). For most of our discussions here, eV is super handy because it’s often directly related to the energy of light.

The fundamental principle at play here is the conservation of energy. Energy can’t just vanish into thin air. When the electron transitions from E_initial to E_final, the difference in energy has to go somewhere. And that somewhere is the photon. So, the energy of the emitted photon (let’s call it E_photon) is simply the difference between these two energy levels.

Here’s the simple, elegant formula:

E_photon = E_initial - E_final

Seriously, that’s it. It’s that straightforward. If you know the starting and ending points of the electron’s energy journey, you know the energy of the light it spits out. Mind. Blown. Right?

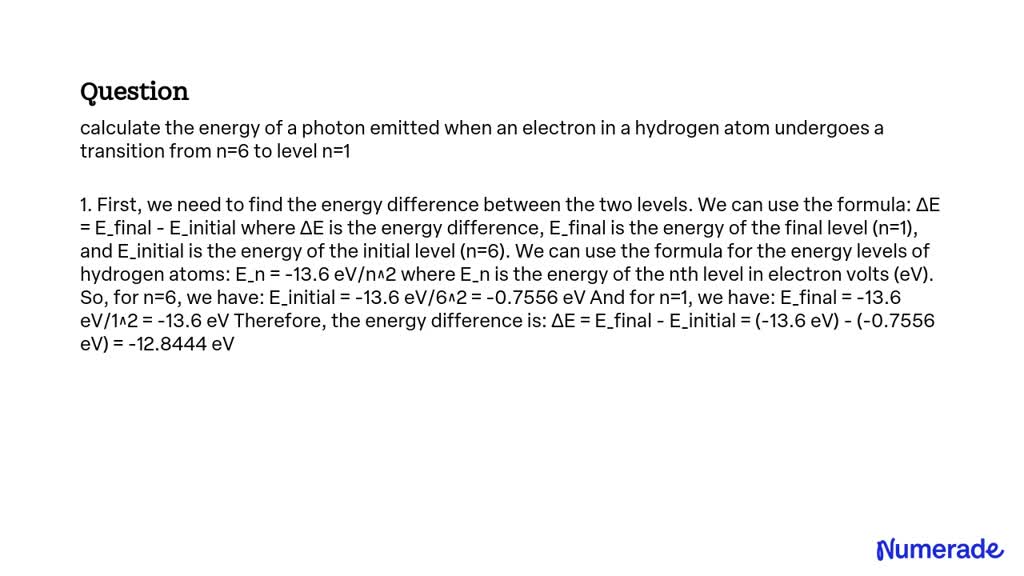

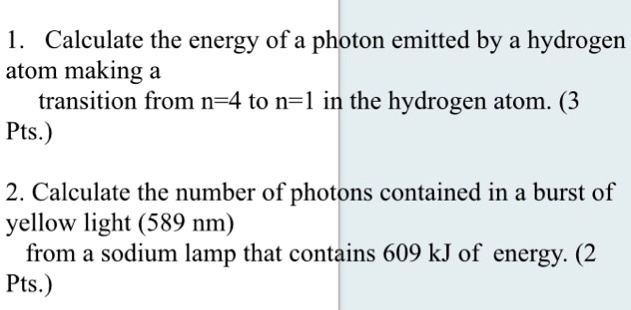

Let’s try a hypothetical example to make this more concrete. Imagine an electron in a hydrogen atom is in the n=3 energy level and it drops down to the n=2 energy level. (In hydrogen, these 'n' numbers represent the energy levels, with lower numbers being lower energy. So, n=1 is the ground state, the most stable level.) The energy associated with the n=3 level in hydrogen is approximately -1.51 eV, and the energy for the n=2 level is approximately -3.40 eV. Remember, these are negative because they represent bound states, but we’re interested in the difference.

So, for our Transition A (let’s call this specific jump from n=3 to n=2 "Transition A" for clarity), our calculation would look like this:

Calculating Energy for Transition A

E_initial (for n=3) = -1.51 eV

E_final (for n=2) = -3.40 eV

Now, plug these values into our formula:

E_photon (Transition A) = E_initial - E_final

E_photon (Transition A) = (-1.51 eV) - (-3.40 eV)

E_photon (Transition A) = -1.51 eV + 3.40 eV

E_photon (Transition A) = 1.89 eV

And there you have it! The energy of the photon emitted during Transition A is 1.89 electronvolts. Pretty neat, right? This energy corresponds to a specific wavelength of light, which for hydrogen atoms making this particular jump, falls in the visible spectrum – specifically, the red light region. This is why hydrogen gas glowed red in some old-school discharge tubes (though the exact colour can be influenced by other transitions and the surrounding gas).

Now, you might be wondering, "Why are the energies negative?" Great question! It’s a convention in atomic physics. The zero point of energy is usually defined as an electron being infinitely far away from the nucleus, completely unbound. To pull an electron away from the nucleus, you need to put in energy. So, any electron bound to the nucleus has less energy than a free electron. Hence, the negative values. When the electron drops to a lower energy state (meaning it’s more bound), it releases energy, and we get a positive photon energy. It’s like digging a hole. The bottom of the hole is at a lower energy level than the ground. To get out of the hole, you need to add energy (climb out). If you fall into the hole, you release potential energy.

It’s also important to remember that these energy levels are very specific to each element. For example, the energy levels in helium are different from those in neon, which are different from argon. This is why different elements emit different colours when excited. That royal purple argon I saw at the museum? That’s because the electrons in argon atoms are jumping between specific energy levels that happen to release photons with energies that our eyes perceive as purple. If it were a different element, with different energy level "rungs," we'd be seeing a whole different light show. It’s like each element has its own unique colour palette.

Sometimes, you might be given the energy levels in joules (J) instead of electronvolts (eV). The conversion is approximately 1 eV = 1.602 x 10^-19 J. So, if your energies are in joules, the calculation is exactly the same, you just use joules throughout. The principle of subtracting the final energy from the initial energy remains constant. It’s just a change of units, like switching from miles to kilometres. The distance is still the same, the way you measure it changes.

You can also use Planck's equation to relate the energy of the photon to its frequency (f) and wavelength (λ):

E_photon = hf

and

c = λf

where 'h' is Planck's constant (approximately 6.626 x 10^-34 J·s) and 'c' is the speed of light (approximately 3.00 x 10^8 m/s). So, if you calculate the photon energy in joules, you can then figure out its frequency and wavelength. This is how scientists can precisely identify elements by looking at the spectrum of light they emit. Each unique spectral line corresponds to a specific electronic transition and therefore a specific photon energy, frequency, and wavelength.

For example, that 1.89 eV photon we calculated earlier? We could convert that to joules (1.89 eV * 1.602 x 10^-19 J/eV ≈ 3.03 x 10^-19 J). Then, using Planck's equation, we could find its wavelength: λ = hc / E_photon. This would give us a wavelength of approximately 656 nanometers, which is indeed in the red part of the visible spectrum!

It’s fascinating to think that something as seemingly simple as a coloured light source is the result of these incredibly precise energy exchanges happening within atoms. Every time you see a coloured neon sign, or the glow of a fluorescent bulb, or even the colours in a rainbow, you're witnessing these quantum leaps and photon emissions. It’s the universe showing off its atomic art, and we’ve just learned how to read the energy signature.

So, next time you see a vibrant colour, don't just think of paint. Think about the electrons, the energy levels, and the little packets of light, the photons, that are carrying that specific energy message. It’s a whole universe of information packed into every glow, and all it takes is a little bit of subtraction to start understanding it. Keep asking questions, keep experimenting (even hypothetically!), and you might just uncover the next secret of the cosmos. Or at least ace that homework assignment. 😉