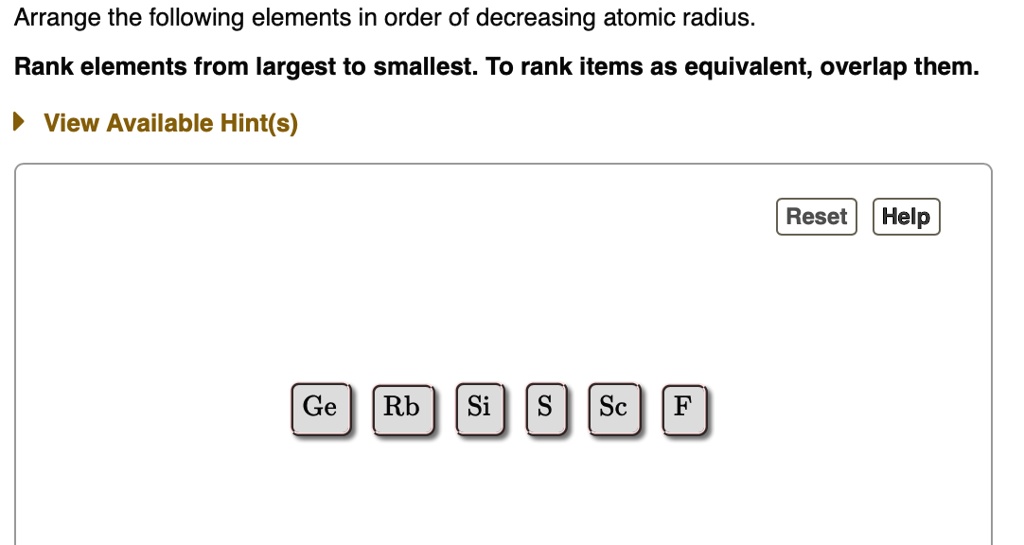

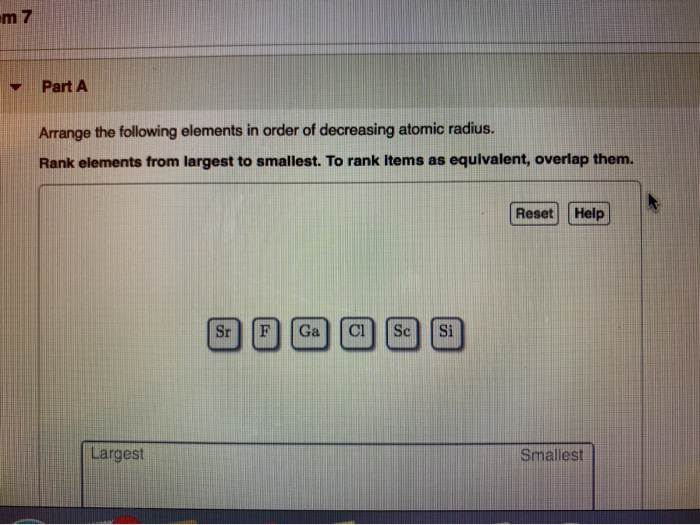

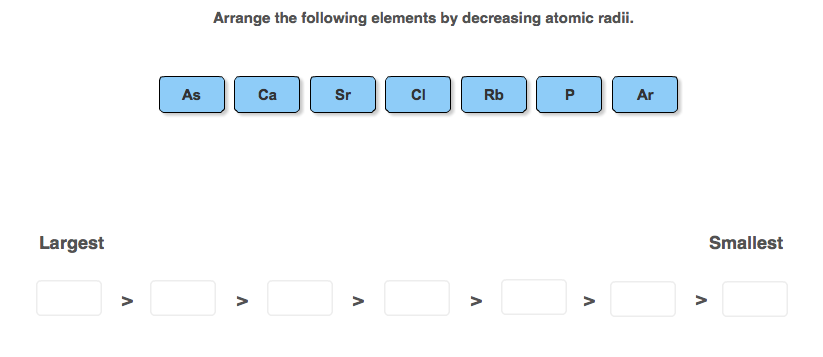

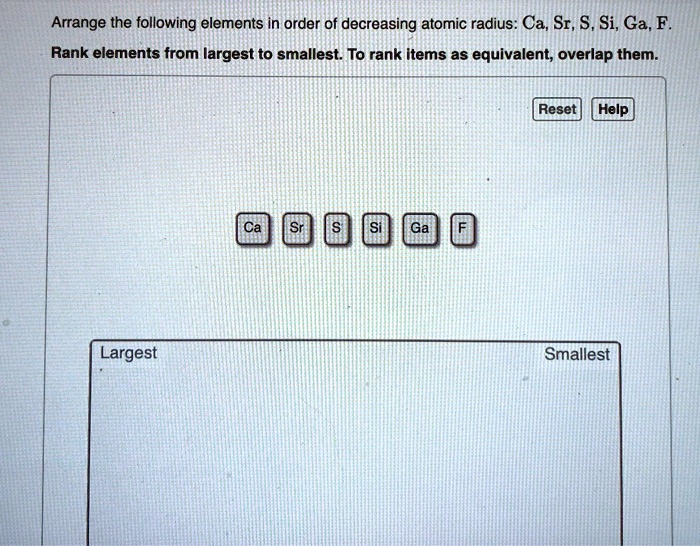

Arrange The Following Elements In Order Of Decreasing Atomic Radius

So, I was rummaging through my junk drawer the other day – you know, that magical place where orphaned socks and forgotten batteries go to retire – and I stumbled upon a tiny, tarnished ring. It wasn't fancy, just a simple band, but it belonged to my grandmother. Holding it, I started thinking about how things shrink and grow, how some things age gracefully and others... well, let's just say they don't. It got me wondering about the tiny building blocks of everything around us, the atoms. Do they, too, have a sense of size that changes?

And that's when it hit me: we're going to talk about atomic radius today! Yep, the size of atoms. Sounds a bit nerdy, right? But trust me, it's one of those fundamental concepts that unlocks so much about how the universe works. Think of it like this: if you want to understand why certain materials bend or break, or why some elements are super reactive and others are basically chilling, you’ve gotta have a handle on their basic dimensions. It's like trying to build IKEA furniture without looking at the instruction manual – you'll end up with a wonky bookshelf and a lot of frustration.

So, the challenge is this: we have a list of elements, and we need to arrange them in order of decreasing atomic radius. That means we start with the biggest atom and end with the smallest. Easy peasy, right? Well, sort of. It’s not quite as simple as measuring a physical object with a ruler. Atoms are… well, they’re atoms. They don’t exactly stand still for a selfie.

Let's break down what we mean by atomic radius first, because, you know, precision is key, even in a chill blog post. It's essentially the distance from the center of an atom's nucleus to its outermost electron cloud. Imagine an atom as a miniature solar system. The nucleus is the sun, and the electrons are the planets orbiting around it. Atomic radius is like the distance from the sun to the farthest point of those orbiting planets. But here’s the kicker: those electrons aren’t neatly in fixed orbits like planets. They're more like a fuzzy, probabilistic cloud. So, scientists have developed different ways to measure this radius, depending on whether the atom is bonded to another atom or if it's chilling by itself.

For our purposes today, we're generally talking about the covalent radius, which is half the distance between the nuclei of two identical atoms bonded together. It's a pretty good representation of an atom's "size" when it's part of a molecule. Think of it as the radius of a spherical atom. Not perfect, but good enough for most of our elemental sizing needs!

Now, there are two main factors that influence atomic radius: the number of electron shells and the effective nuclear charge. These two amigos have a tug-of-war going on, and the winner dictates how big that atom is going to be. It’s like a constant battle for territory within the atom itself!

First up, the number of electron shells. This is pretty straightforward. Atoms have electrons arranged in different energy levels, or shells, around the nucleus. The further away an electron shell is from the nucleus, the more space it occupies. So, the more electron shells an atom has, the larger its atomic radius will generally be. It's like adding more floors to a building – it just gets taller.

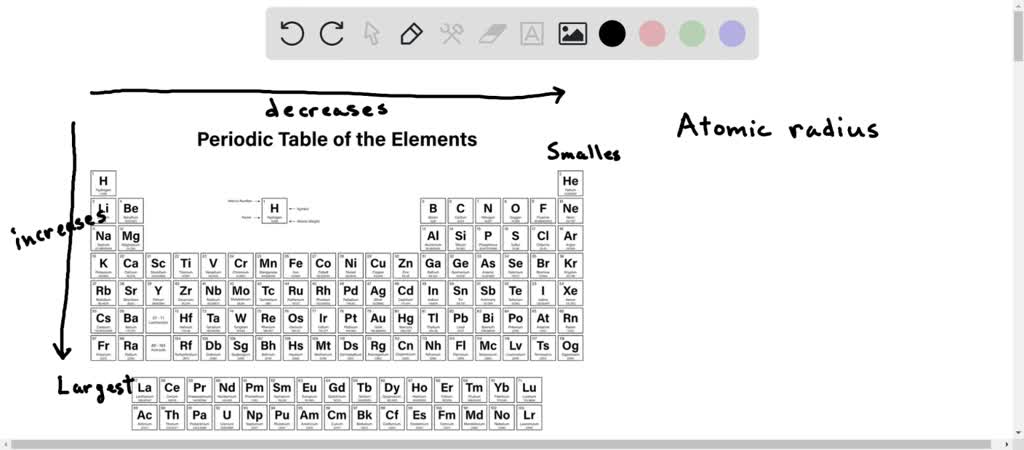

Think about the periodic table. When you move down a group (a vertical column), you’re adding another electron shell with each new element. So, elements at the bottom of a group are going to be significantly larger than elements at the top. This is a major trend you need to keep in mind. It’s a pretty reliable indicator of size.

The second factor is the effective nuclear charge. This one’s a bit trickier but super important. The nucleus has positively charged protons, and the electrons are negatively charged. These opposite charges attract each other. The effective nuclear charge is the net positive charge experienced by an electron in an atom. It’s basically how strongly the nucleus is pulling on those outer electrons.

Now, the number of protons in the nucleus increases as you move across a period (a horizontal row) from left to right. This means the positive charge of the nucleus is getting stronger. However, the number of electron shells stays the same within a period. So, even though there are more protons pulling, those inner electrons are essentially shielding the outer electrons from the full nuclear charge. It's like having a strong magnet, but putting a bunch of metal plates between it and something you want to attract. The pull is still there, but it's reduced.

As you move from left to right across a period, the effective nuclear charge increases. This stronger pull from the nucleus draws the electron cloud closer, making the atom smaller. So, elements on the left side of a period tend to be larger than elements on the right side. It’s a bit counterintuitive because you have more protons, which you might think would make things bigger, but the increased pull compacts the electron cloud.

So, to recap our trends: * Moving down a group: Atomic radius increases (more electron shells). * Moving across a period (left to right): Atomic radius decreases (increased effective nuclear charge).

These two trends work together to determine the overall size of an atom. It’s a constant balancing act between the number of electron layers and the strength of the nuclear "hug."

Alright, let’s get to the good stuff. We've got a list of elements here, and we need to put them in order of decreasing atomic radius. This means we start with the biggest dude and work our way down to the tiniest. The elements are: Sodium (Na), Chlorine (Cl), Potassium (K), and Bromine (Br).

First, let's locate these guys on the periodic table. This is your best friend when dealing with atomic trends. * Potassium (K): Atomic number 19. Group 1, Period 4. * Sodium (Na): Atomic number 11. Group 1, Period 3. * Bromine (Br): Atomic number 35. Group 17, Period 4. * Chlorine (Cl): Atomic number 17. Group 17, Period 3.

Now, let's analyze them using our trends. We have two elements in Group 1 (the alkali metals): Potassium (K) and Sodium (Na). We have two elements in Group 17 (the halogens): Bromine (Br) and Chlorine (Cl).

Let's compare the elements within each group first. In Group 1, Potassium (K) is in Period 4, and Sodium (Na) is in Period 3. Since Potassium is in a lower period, it has more electron shells. Therefore, Potassium (K) is larger than Sodium (Na). This is our first comparison: K > Na.

Now, let's look at Group 17. Bromine (Br) is in Period 4, and Chlorine (Cl) is in Period 3. Similar to the alkali metals, Bromine is in a lower period, meaning it has more electron shells. Thus, Bromine (Br) is larger than Chlorine (Cl). Our second comparison: Br > Cl.

So far, we know that both K and Br are larger than their counterparts Na and Cl, respectively. Now we need to compare elements from different groups but in the same period, and also elements in the same group but different periods. This is where the interplay of trends becomes crucial.

Let's compare elements from Group 1 and Group 17 within the same period. Consider Period 4: we have Potassium (K) in Group 1 and Bromine (Br) in Group 17. Potassium is on the far left of Period 4, while Bromine is on the far right. When moving across a period from left to right, the atomic radius decreases due to increasing effective nuclear charge. Therefore, Potassium (K) is larger than Bromine (Br). This is our third comparison: K > Br.

Now consider Period 3: we have Sodium (Na) in Group 1 and Chlorine (Cl) in Group 17. Sodium is on the far left of Period 3, and Chlorine is on the far right. Again, moving across the period, the atomic radius decreases. So, Sodium (Na) is larger than Chlorine (Cl). Our fourth comparison: Na > Cl.

Let's piece together what we have:

- K > Na (Potassium is larger than Sodium because it's in a lower period)

- Br > Cl (Bromine is larger than Chlorine because it's in a lower period)

- K > Br (Potassium is larger than Bromine because K is on the left of Period 4, Br is on the right)

- Na > Cl (Sodium is larger than Chlorine because Na is on the left of Period 3, Cl is on the right)

We want the order of decreasing atomic radius, meaning from largest to smallest.

Let's compare K and Br. We already established K > Br. Now let's compare K with Na and Cl. We know K > Na and K > Cl. So, K is likely the largest. Let's compare Br with Na and Cl. We know Br > Cl. We also know K > Br. What about Br vs Na? Bromine is in Period 4, Group 17. Sodium is in Period 3, Group 1. While Na has fewer electron shells, Br has a significantly higher nuclear charge and is further to the right. Generally, the effect of adding a shell (moving down a group) is more pronounced than the effect of increasing nuclear charge across a period, especially when comparing elements in the same period. However, when comparing across periods, it's a bit more nuanced. For K and Br, both are in Period 4. K is in Group 1, Br is in Group 17. K has only one valence electron and is on the far left, while Br has seven valence electrons and is on the far right. The nuclear charge in Br is much higher. This stronger pull in Br compacts its electrons more than in K. So, K is indeed larger than Br.

Now, let's think about Na and Br. Sodium is in Period 3, Group 1. Bromine is in Period 4, Group 17. Sodium has 3 electron shells. Bromine has 4 electron shells. Even though Bromine has a much higher effective nuclear charge due to more protons, the extra electron shell in Bromine usually makes it larger than Sodium. So, Bromine (Br) is larger than Sodium (Na). This is a key comparison. Let's call this comparison Br > Na.

Let's summarize our pairwise comparisons again, and try to build the chain:

- K is in Period 4, Group 1.

- Br is in Period 4, Group 17.

- Na is in Period 3, Group 1.

- Cl is in Period 3, Group 17.

We know moving down a group increases radius. So, elements in Period 4 will be larger than their counterparts in Period 3. This means K > Na and Br > Cl.

We know moving across a period decreases radius. So, elements on the left are larger than elements on the right. This means K > Br and Na > Cl.

Let's combine these. K is in Period 4, Group 1. It has 4 shells and low nuclear charge pull. It should be quite large. Br is in Period 4, Group 17. It has 4 shells but high nuclear charge pull. It should be smaller than K. Na is in Period 3, Group 1. It has 3 shells and low nuclear charge pull. It should be smaller than K. Cl is in Period 3, Group 17. It has 3 shells and high nuclear charge pull. It should be the smallest of this group.

Let's try to order them now, starting with the largest:

Potassium (K): It's in Period 4, Group 1. It has the most electron shells among these elements that is compared in the same group downwards, and it's on the far left of its period. This generally makes it one of the largest. K > Na and K > Br confirmed by our previous logic.

Next, let's consider Bromine (Br). It's in Period 4, Group 17. It has 4 shells, same as K, but it's on the far right of the period, so its radius is smaller than K due to increased nuclear charge. However, it has more shells than Na and Cl. We established Br > Na and Br > Cl. So, K is the largest, and Br is likely the second largest.

Now we compare Sodium (Na) and Chlorine (Cl). Sodium is in Period 3, Group 1. Chlorine is in Period 3, Group 17. Sodium has 3 shells, and is on the left of the period. Chlorine has 3 shells, and is on the right. Since Na is on the left of the period, and Cl is on the right, Na should be larger than Cl. Na > Cl confirmed.

Let's re-evaluate the Br vs Na comparison. K (Period 4, Group 1) Br (Period 4, Group 17) Na (Period 3, Group 1) Cl (Period 3, Group 17) We know that moving DOWN a group increases size. So, Period 4 elements are generally larger than Period 3 elements. K is in Period 4. Na is in Period 3. K > Na. Br is in Period 4. Cl is in Period 3. Br > Cl. We know that moving ACROSS a period (left to right) decreases size. K is on the left of Period 4. Br is on the right of Period 4. K > Br. Na is on the left of Period 3. Cl is on the right of Period 3. Na > Cl. So, K is definitely the largest. Then we need to compare Br and Na. K (4 shells, Group 1) Br (4 shells, Group 17) Na (3 shells, Group 1) Cl (3 shells, Group 17) K has 4 shells, Br has 4 shells. K is on the left, Br on the right. K > Br. Na has 3 shells, Cl has 3 shells. Na is on the left, Cl on the right. Na > Cl. Now we compare K (Period 4, Group 1) with Na (Period 3, Group 1). K is larger because of the extra shell. Now we compare Br (Period 4, Group 17) with Cl (Period 3, Group 17). Br is larger because of the extra shell. The question is now, is Br larger than Na? Br is Period 4, Group 17. It has 4 shells. Na is Period 3, Group 1. It has 3 shells. Generally, adding a full electron shell has a larger impact on atomic radius than moving across a period. So, an element in Period 4 is usually larger than an element in Period 3, even if the Period 4 element is on the far right and the Period 3 element is on the far left. Therefore, Bromine (Br) is larger than Sodium (Na). This confirms our earlier intuition about Br > Na. So, the order of decreasing atomic radius should be: 1. Potassium (K): Largest, Period 4, Group 1. 2. Bromine (Br): Second largest, Period 4, Group 17. It's in the same period as K, but further right, so smaller. 3. Sodium (Na): Third largest, Period 3, Group 1. It has fewer shells than K and Br, but is still on the left side. 4. Chlorine (Cl): Smallest, Period 3, Group 17. It has the fewest shells and is on the far right of its period. So, the order of decreasing atomic radius is: K > Br > Na > Cl.

Isn't that cool? It's like solving a little puzzle with the periodic table as your guide. You can almost visualize these atoms growing and shrinking based on their position. It's a powerful reminder that even the tiniest particles in the universe follow predictable rules.

So next time you look at a periodic table, don't just see a bunch of symbols. See a map of sizes, a landscape of electron clouds, and a testament to the elegant order that governs everything. And hey, if you ever find yourself with a mysterious orphaned ring, maybe you can ponder its atomic radius. Just kidding... mostly.

Remember these trends: down is bigger, left is bigger. That's your cheat sheet for most things atomic radius! Happy puzzling!