Arrange The Elements In Decreasing Order Of First Ionization Energy

So, I was rummaging through my dad's old science textbooks the other day – you know, the ones that smell vaguely of dust and regret? He was a chemist, bless his cotton socks, and he had this… thing for the periodic table. Like, he could identify elements by smell, probably. Anyway, I stumbled across this worksheet, all crinkled and yellowed, with a list of elements and a big, bold instruction: "Arrange The Elements In Decreasing Order Of First Ionization Energy." My immediate thought? "Uh, what now?"

Now, I'm no stranger to a bit of scientific jargon, but "ionization energy" felt like something out of a sci-fi novel. It sounded… aggressive. Like electrons were having a full-on wrestling match. But hey, curiosity is a powerful force, right? And since my dad isn't around to explain it over a cup of lukewarm tea, I decided to dive in myself. And let me tell you, it's a lot more interesting than it sounds. Way more interesting than just memorizing atomic numbers, anyway. So, grab yourself a beverage – maybe something strong, depending on how much you like chemistry – and let's unravel this ionization energy mystery together.

The Great Electron Escape: What Even IS Ionization Energy?

Alright, let's break it down. Imagine an atom. It's got a nucleus, right? That's the grumpy old man at the center, packed with protons and neutrons. Then you've got electrons zipping around, like hyperactive kids in a playground. Now, these electrons aren't just chilling; they're held in place by the attraction to the positively charged nucleus. Think of it like a tiny, cosmic game of tetherball, but with electro-magnetic forces.

First ionization energy, in its most basic form, is the energy required to remove the outermost, or valence, electron from a neutral atom in its gaseous state. So, we're talking about giving that little electron enough of a shove, enough energy, to break free from the atom's grasp. It's like convincing that one kid who really wants to go on the slide to finally leave the swingset. You gotta offer them something pretty enticing, right?

Why "first"? Well, you can keep stripping electrons away, but that first one is usually the easiest to nab. It's the one that's farthest from the nucleus and least tightly held. Think of it as the first cookie you grab from the jar – it's the most accessible. The subsequent ionization energies (second, third, etc.) get progressively harder, because you're removing an electron from an already positively charged ion, which makes the attraction stronger. But for our purposes today, we're focusing on that initial, big effort.

The Periodic Table's Secret Hierarchy: Why Some Atoms Are More "Sticky" Than Others

This is where the periodic table, that iconic chart of elements, really shines. It's not just a pretty display; it's a roadmap of atomic behavior. And ionization energy follows some very predictable trends across it. It's like knowing that in any given social situation, the loudest person is probably going to be near the snack table. Predictable, right?

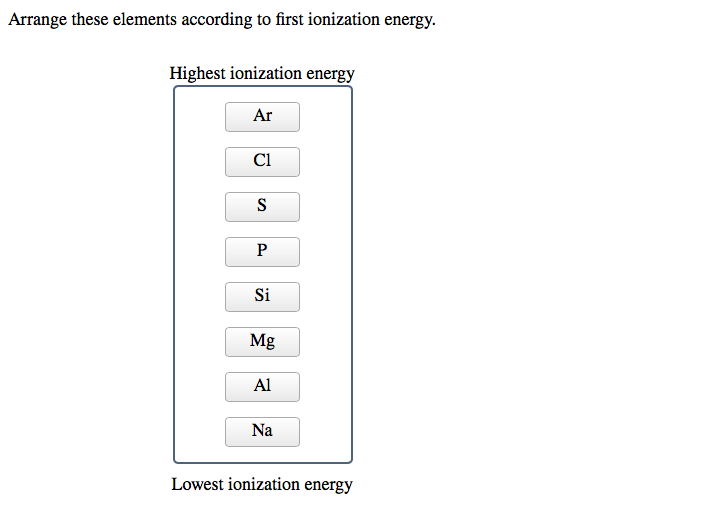

There are two main directions you need to consider: moving across a period (left to right) and moving down a group (top to bottom).

Across a Period: The Nuclear Squeeze

Let's start by moving from left to right across a row, or period, on the periodic table. Think of elements like Lithium (Li), Beryllium (Be), Boron (B), Carbon (C), Nitrogen (N), Oxygen (O), Fluorine (F), and Neon (Ne).

As you move from left to right in a period, the number of protons in the nucleus increases. This means the nucleus has a stronger positive charge. Now, crucially, the electrons are being added to the same electron shell (or energy level). So, you've got a stronger pull from the center, but the electrons are all hanging out at roughly the same distance. It's like having a stronger magnet, but all the metal filings are still in the same general area. The nucleus can therefore hold onto its electrons much more tightly.

Therefore, ionization energy generally increases as you move from left to right across a period. Elements on the far left (like alkali metals – think Sodium, Potassium) are pretty eager to give up an electron to achieve a stable electron configuration. They're the ones practically throwing electrons at you. Elements on the far right (like halogens – think Fluorine, Chlorine) are much more reluctant. They want to grab electrons, not give them away. And the noble gases? They're the ultimate introverts, perfectly content with their electron setup. Giving up an electron for them would be like asking them to voluntarily stand up and sing karaoke. Not happening.

You might notice a little hiccup here and there, like a tiny dip between groups 2 and 13, or 15 and 16. These are due to the subtle effects of electron shell filling and repulsion, but the overall trend of increasing ionization energy across a period is a solid rule of thumb. Think of them as minor plot twists in an otherwise straightforward narrative.

Down a Group: The Shielding Effect and Distance

Now, let's switch gears and look at moving down a column, or group. Consider elements like Hydrogen (H), Lithium (Li), Sodium (Na), Potassium (K), Rubidium (Rb), and Cesium (Cs).

As you move down a group, the number of protons increases, which would suggest a stronger nuclear pull, right? BUT, and this is a big BUT, the electrons are being added to new, higher energy shells. These outer shells are further away from the nucleus. It’s like the kids are moving to different floors of the house – the parents on the ground floor have less influence on the ones on the third floor.

Furthermore, the inner electrons (the ones in the shells closer to the nucleus) act as a sort of shield. They get between the nucleus and the outermost electrons, blocking some of that attractive force. Think of it like a thick curtain between you and the TV. You can still see it, but the image isn't as clear or as intense.

Because of this increased distance and the shielding effect, the nucleus's hold on the outermost electron weakens significantly as you go down a group. It becomes much easier to pull that electron away.

Therefore, ionization energy generally decreases as you move from top to bottom down a group. The alkali metals at the very bottom of their group (like Cesium and Francium) have incredibly low ionization energies. They're practically giving their electrons away for free. It's like finding a dollar on the sidewalk – easy peasy.

Putting It All Together: The Decreasing Order Challenge

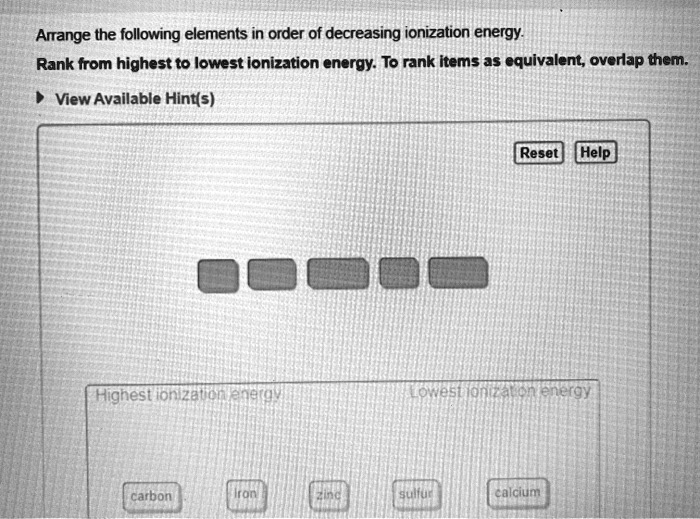

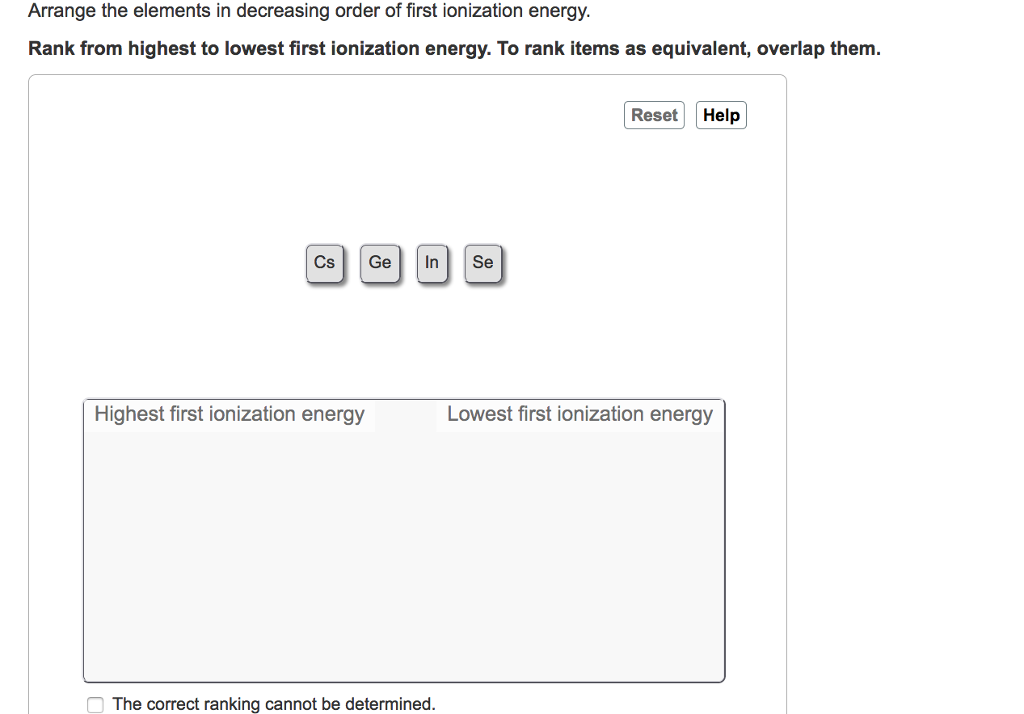

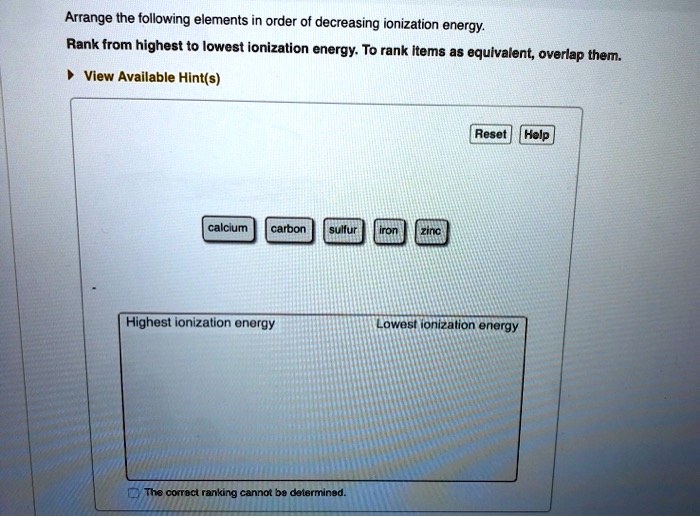

So, the challenge is to arrange elements in decreasing order of first ionization energy. This means we want to go from the element that's hardest to take an electron from, to the one that's easiest. Based on our trends, where should we start looking?

We know that ionization energy increases across a period and decreases down a group. This implies that the elements with the highest ionization energies will be found in the upper-right corner of the periodic table (excluding noble gases, which are often considered a separate category in these trends because their full outer shells make them exceptionally stable and thus have very high ionization energies, but are often excluded from direct comparisons in simpler exercises). Conversely, the elements with the lowest ionization energies will be in the lower-left corner.

Let's take a hypothetical list of elements to arrange. Imagine we had to order: Magnesium (Mg), Sulfur (S), Potassium (K), and Chlorine (Cl).

First, let's locate them on the periodic table:

- Potassium (K): Group 1, Period 4. Far left, lower down.

- Magnesium (Mg): Group 2, Period 3. To the right of K, but higher up.

- Chlorine (Cl): Group 17, Period 3. Far right, same period as Mg.

- Sulfur (S): Group 16, Period 3. Just to the left of Cl, same period as Mg.

Now, let's apply our trends:

Going down a group: Potassium (K) is in a lower period than Magnesium (Mg), so K should have a lower ionization energy than Mg.

Going across a period: Within Period 3, we have Mg, S, and Cl. Ionization energy increases from left to right. So, Mg < S < Cl.

Combining these:

- K is way down on the left, so it's going to have a very low ionization energy.

- Mg is to the right of K and higher up, so it will have a higher ionization energy than K.

- S is to the right of Mg, so it will have a higher ionization energy than Mg.

- Cl is to the right of S, so it will have the highest ionization energy among Mg, S, and Cl.

Therefore, in decreasing order of first ionization energy (from highest to lowest):

Chlorine (Cl) > Sulfur (S) > Magnesium (Mg) > Potassium (K)

See? It's like solving a puzzle! You just need to know the rules of the game.

The Ironic Twist: Why Noble Gases Are the Ultimate "No Thanks"

Now, about those noble gases (Helium, Neon, Argon, Krypton, Xenon, Radon). They are in Group 18. Their electron shells are completely full. They're like that person at the party who is perfectly happy standing in the corner, not interacting with anyone, and not needing anything. They've achieved electron nirvana.

Because they have a full, stable electron configuration, it takes an enormous amount of energy to try and pry an electron away from them. Their ionization energies are generally the highest within their respective periods. So, if you were asked to include Neon (Ne) in our previous list (Mg, S, K, Cl), it would slot in at the very top, because it's in Period 3 and on the far right, with a full outer shell.

The order would then be: Neon (Ne) > Chlorine (Cl) > Sulfur (S) > Magnesium (Mg) > Potassium (K). It's almost ironic, isn't it? The elements that are least reactive, the ones that are most content, are the ones that require the most effort to disturb. It’s a testament to their stability.

The Practicalities (and the Irony of My Dad's Worksheet)

So, why did my dad have this worksheet? Well, understanding ionization energy is crucial in chemistry. It helps predict how elements will react, what kinds of bonds they'll form, and generally how they'll behave. For example, elements with low ionization energies (like the alkali metals) are highly reactive because they readily give up electrons to form positive ions. This is why sodium explodes in water – it's desperate to lose that electron and achieve a more stable configuration. Intense!

Elements with high ionization energies (like the halogens) are also reactive, but in a different way. They tend to gain electrons to achieve a full outer shell. This attraction for electrons is what makes them good oxidizing agents.

And then there are the elements in the middle, with moderate ionization energies, who might be happy to share electrons through covalent bonding.

The irony of my dad's worksheet, I guess, is that while it seems like a dry academic exercise, it's actually the key to understanding the entire dynamic dance of chemical reactions. It’s the secret handshake of the elements. And now, armed with this knowledge, I can finally appreciate the meticulous, almost obsessive, way he organized his chemistry notes. He wasn't just being nerdy; he was deciphering the universe's fundamental building blocks.

So, next time you look at the periodic table, don't just see a bunch of boxes. See a hierarchy, a story of electron escape, and a world of predictable (and sometimes wonderfully ironic) chemical behavior. And if you ever find yourself staring at a similar worksheet, you'll know exactly what to do. You've got this! Now, if you'll excuse me, I think I hear some electrons calling for their ionization energy. Just kidding… mostly.